Author(s)

Nina Valerie Kolowratnik

When Indigenous communities are asked to provide proof of their connection to ancestral lands, what Western legal forums accept as documentation does not truly represent or respect tribal culture and traditional formats of knowledge transfer.

Responding to the experiences of evidence production by Jemez Pueblo members in New Mexico, Nina Valerie Kolowratnik’s research challenges the conditions under which Indigenous rights to protect and regain traditional land are negotiated in United States legal frameworks.

When Indigenous communities claim their rights to traditional land in United States legal forums, the burden of proof is on the Native plaintiff. To prove their claim to ancestral land, the community must show evidence of current and continued “use and occupancy.” And while Indigenous peoples’ ways of life, including farming, hunting, and ceremonial practices on the land, are accepted in court as proof of the existence of Aboriginal title, the formats of evidence that the US legal and judicial system considers reliable are mostly limited to empirical facts. Oral histories—the primary method of knowledge production and transmission within most Native communities—are often reduced to hearsay status, and remain unheard, as they can’t be evaluated according to Western scientific standards. Western law strives for definite statements and expert knowledge that can be attributed to individuals. Oral histories do not have a set starting point or end, they cannot be traced back to one single originator, they often vary according to the individual creative expression of the storyteller, they are alive. And it is precisely because intergenerational memory can only be performed when a community’s traditional culture is continuously practiced, that the oral format itself represents the embodiment and proof of a Native group’s continuous history.

Asked to provide proof in a Western court, Native plaintiffs face a conceptual and structural change in knowledge transmission, when dynamic, oral history is translated into static Western forms of recording. They must also engage in a complex interrelationship between power and access to knowledge. The process of producing evidence runs counter to many Indigenous communities’ structural organization around multi-layered cultural secrecy and positions them in a double bind. Are they to remain silent because of their cultural demands to guard traditional knowledge, or do they comply with the imposed Western evidentiary criteria—which asks them to pin-point sacred sites and give detailed descriptions of rituals and when they are performed—thereby risking to silence the traditional practices they are aiming to protect?

The Language of Secret Proof is a research project which builds on responses to evidence production for a land claim by the sovereign Indigenous nation Jemez Pueblo, one of nineteen Pueblo nations in the American Southwest. Within this project, Pah-Tow-Wei Paul Tosa, Sée-Shu-Kwa Christopher Toya of Jemez Pueblo, and I devised an alternative set of evidentiary drawings that provide proof of the pueblo’s connection to the lands and speak about the importance the sacred grounds hold in the Jemez Pueblo tradition, while holding on to their secrets. 1

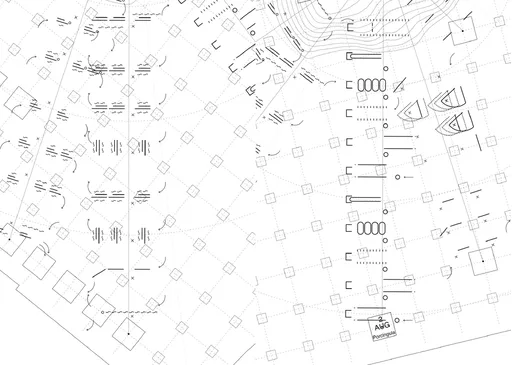

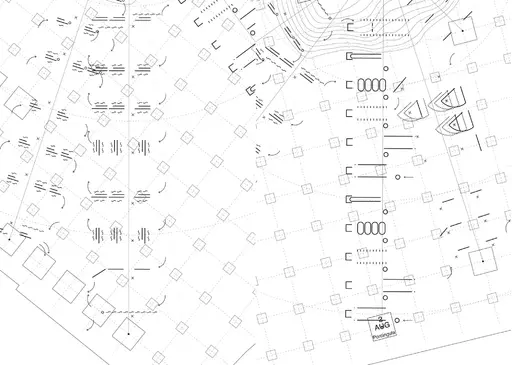

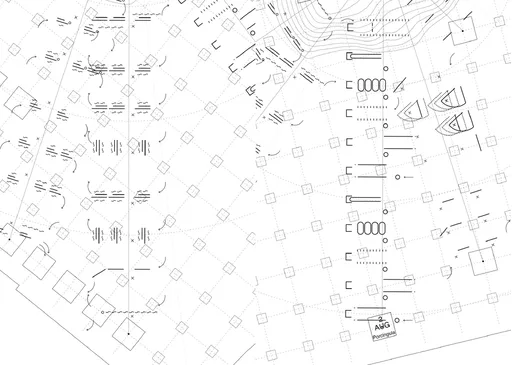

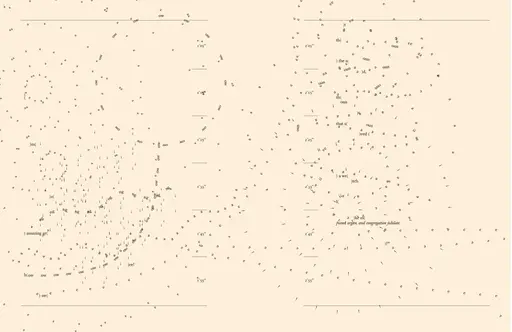

The drawing titled Hemish Spiritual Pathway documents the spiritual connection between the Hemish people 2 and the shrine on Wâavemâ Mountain, located within the area claimed. It focuses on the ceremonial dances that structure the traditional Hemish calendar year and are performed on specific days on the plaza of Jemez Pueblo. Each dance sequence has a specific role in soliciting the blessings of the spirits residing on Wâavemâ Mountain; thus, dance movements and sequences are seen as a communication system and spatial manifestation of the spiritual pathway.

The drawing thus represents a cyclical calendar which is linked to moments of connection between the Pueblo and the spirits. Ancestral spirit relations and the times in which they must be enacted embody a temporality that cannot be captured by a standardized Western model of linear time. The drawing needs to represent a non-linear, non-directed, but repeating calendar, and a calendar without specific dates or time-frames, as all of the dances—except for two—are closed to the public, and the days they are performed remain undisclosed to outsiders. Dancers, ritual masks, paraphernalia, clothing, and the meanings behind the symbolism and dance movements are excluded from visual representation as well. The notational system adheres to what anthropologist Elizabeth Brandt has outlined as the lowest category of traditional knowledge: the knowledge a non-Pueblo spectator gains when witnessing a ceremonial dance. 3 Since the non-Pueblo spectator is unable to understand the meaning of the dance and its role in the culture, this knowledge remains incomplete and fragmented, hence harmless to Hemish tradition.

Linking individual traditional knowledge with the meanings of the symbols should allow Hemish people to read the blank spaces and “complete” the drawing, similar to the concept of speech images within oral history. To an outsider and to a legal audience, the only “accessible” components of the drawings are the encrypted representations, which in this case provide the proof, perhaps paradoxically, of secret knowledge.

2 In 1909, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names named the Hemish people’s town “Jemez,” which derives from the Spanish colonial pronunciation, although the Indigenous nation calls its people, traditional land, and culture “Hemish.” Following the advice of See-Shu-Kwa Christopher Toya of Jemez Pueblo, I use “Hemish” when referring to the people, traditional land, and culture, and “Jemez” when referring to legal and political matters.

3 Elizabeth A. Brandt, “The Role of Secrecy in a Pueblo Society,” in Flowers of the Wind: Papers on Ritual, Myth, and Symbolism in California and the Southwest, ed. Thomas C. Blackburn (Socorro, NM: Ballena Press, 1977), pp. 14–15.

For a more detailed account of Nina Valerie Kolowratnik’s research on this topic, see The Language of Secret Proof: Indigenous Truth and Representation (Berlin/New York: Sternberg Press, 2019). The drawing Hemish Spiritual Pathway was first published in that book.

Related

“Rhythm Travel” (1995) was published in Amiri Baraka’s short story collection, Tales of the Out & the Gone (Brooklyn: Akashic Books, 2007), republished here with kind permission of Akashic Books.

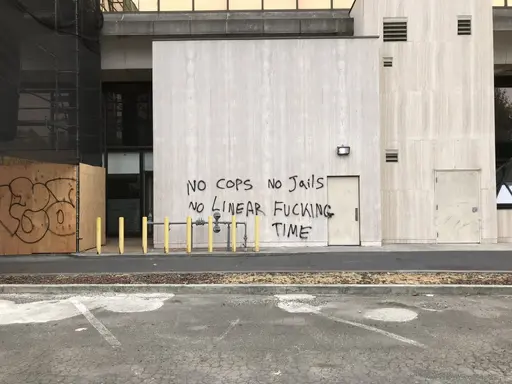

Temporal drag, erotohistoriography, chronomornativity, horniness under capitalism, rhythm, dancing, and crip time.

Black Quantum Futurism (Camae Ayewa and Rasheedah Phillips) in conversation with Jeanne van Heeswijk and Rachael Rakes.

“The Clearing: Music, Dysfluency, Blackness, and Time” was originally published in Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies, 5, no. 2, 2020, pp. 215–233 and is republished here in revised form with kind permission of the author.

When Indigenous communities are asked to provide proof of their connection to ancestral lands, what Western legal forums accept as documentation does not truly represent or respect tribal culture and traditional formats of knowledge transfer.

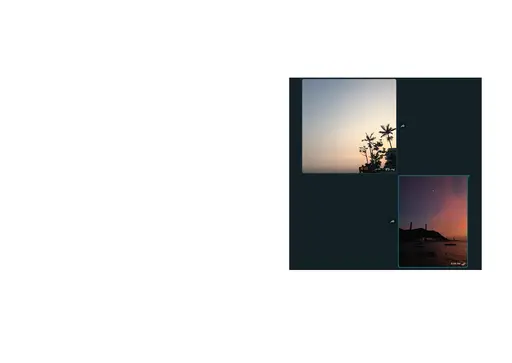

How do we reckon with our attachments to place, and their knotted historical relations? A meditation on maritime trade routes, SEA – SHIPPING – SUN (2021), is a short film directed by Tiffany Sia and Yuri Pattison shot over the span of 2 years to render a simulated duration of a day, from The film is set against a soundtrack of shipping forecasts from archival BBC Radio 4 broadcasts. The sun emerges and disappears, again and again.dawn until dusk.

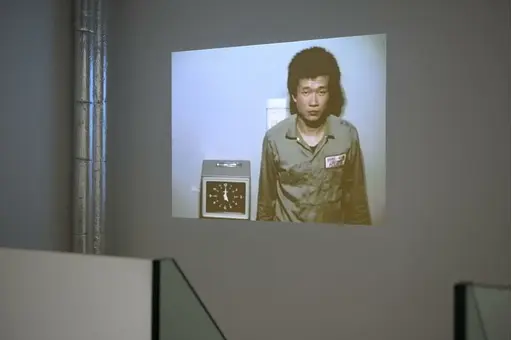

In this essay, Amelia Groom responds to Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980–1981: Time Clock Piece (1980–1981), one of the works on view as part of the No Linear Fucking Time exhibition at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Through a reading of Dolly Parton’s contemporaneous antiwork anthem 9 to 5 (1980), Groom reflects on historical shifts in the ways that workers have been and continue to be exploited through techniques and technologies of time.

Grappling with the imposed linearity of timespace as a fundamental feature of colonial violence, this essay by Promona Sengupta (also known as Captian Pro of the interspecies intergalactic FLINTAQ+ crew of the Spaceship Beben) proposes a mode of time travel that is “untethered from colonial imaginations of the traversability of time and space.”

Weird Times (2021), is a 30-page chapbook by artists Tiffany Sia and Yuri Pattison on time-telling and hegemony. Featuring writing by Sia and images selected by Pattison, it is a brief history of the development of time-keeping technologies. The clock is disassembled as a political tool, a metronome of coercion and an accelerant of war power. Out of these mechanisms, resistant counter-tempos emerge.

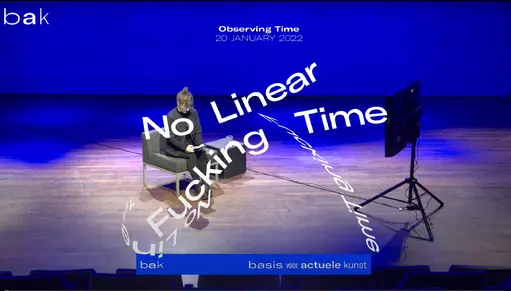

An online conversation with performance artist Tehching Hsieh, writer Amelia Groom, and writer and curator Adrian Heathfield, moderated by BAK curator of public practice Rachael Rakes on 20 January 2022. The conversation takes Hsieh’s work as a starting point in addressing performative time, labor time, gaps, and rhythms of endurance, among other things.

The “No Linear Fucking Time Bibliography” is an evolving resource which compiles selected scholarly and artistic texts relating to the various strands of study involved in this project.

In “Reclaiming Time: On Blackness and Landscape” (first published in PN Review 257 in 2021), poet Jason Allen-Paisant traces the racialized social contexts and modern environmental constructs that “disproportionately rob Black lives of the benefits of time.”

While walking through the “Nothing To Declare” arrivals gate at London Stansted Airport, Sam Keogh is confronted by three border guards: a pig, a unicorn, and a worried cartoon clock.

In this conversation with Walidah Imarisha (first published in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, published by BAK and MIT Press, 2021), the writer and activist outlines her concept of “visionary fiction” as an imaginative practice to emancipate futures from the stronghold of linear time.

Drawing from her work as part of the Karrabing Film Collective, Elizabeth A. Povinelli’s essay “In Some Places the Not-Yet Has Long Been Already” (which first appeared in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, published by BAK and MIT Press, 2021) contrasts the temporal orientation of late settler liberalism—which is troubled by the coming catastrophes of climate collapse—with the ancestral catastrophes of coloniality and enslavement, which are both past and present.

Designed by Rissa Hochberger, with additional design by JJJJJerome Ellis and Kelvin Ellis, the book The Clearing is the eighth title in Wendy’s Subway’s Document Series, an interdisciplinary publishing initiative highlighting the work of time-based artists in printed form.

In her text “Dearest Zen (Letters to Lichen),” artist and scientist Adriana Knouf presents future love letters written to lichens, symbiotic organisms of fungi and algae or cyanobacteria.

In “Immortals: On the Ancient Future Lives of Stone and Plastic,” Marianne Shaneen blends stories, histories, and ontologies of two substances: stone and plastic.

“The Clearing: Melismatic Palimpsest” is a part of musician and writer JJJJJerome Ellis’s multi-faceted project The Clearing (book published by Wendy’s Subway and album of the same name released by NNA Tapes, 2021). Conceiving of the forest and its clearings as “sites of resistant black oralities for centuries,” Ellis explores how stuttering, blackness, and music can figure within practices of refusal against the hegemonic governance of time, speech, and encounter.