Author(s)

Amelia Groom

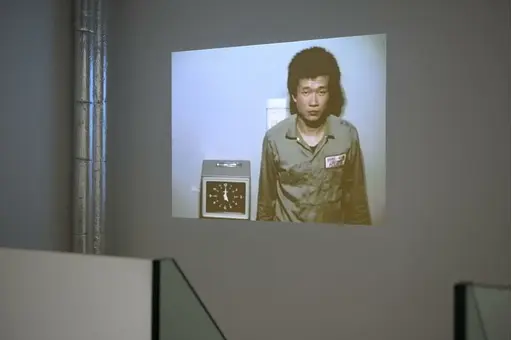

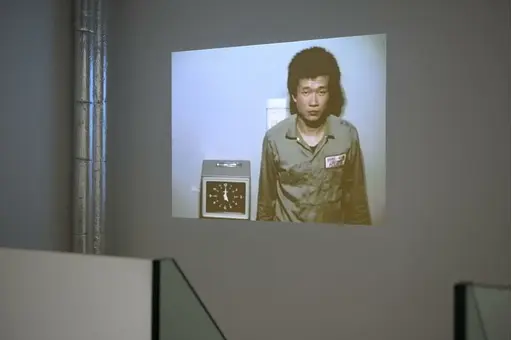

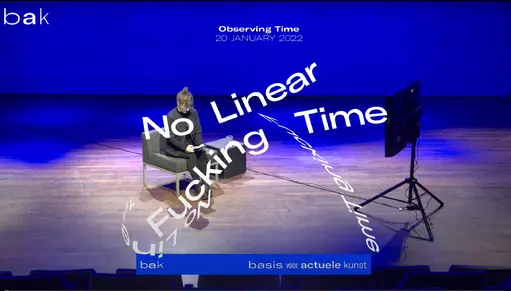

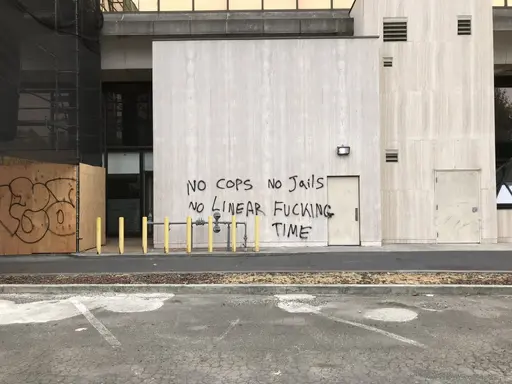

In dit essay reageert Amelia Groom op Tehching Hsieh's werk Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981) (1980-1981), een van de stukken die te zien is als onderdeel van de tentoonstelling No Linear Fucking Time bij BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Door een lezing van het gelijktijdige anti-werk lied 9 to 5 (1980) van Dolly Parton reflecteert Groom op de historische verschuivingen in de manieren waarop werknemers werden en nog steeds worden uitgebuit door technieken van tijdsdiscipline.

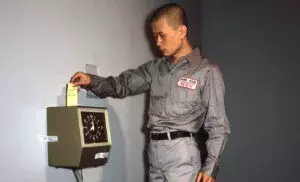

At the foreground of the work’s multiple temporal registers are two standard units of time: the hour and the year. But while the imposed mechanical structure of clock-time is perversely obeyed across an entire annual cycle, other temporal measures are completely disregarded. Units that are longer than an hour but shorter than a year—weeks, months, seasons—are bypassed, and diurnal rhythms of light and dark—perhaps our most primal marker of time’s passage—as well as the body’s circadian rhythms and sleep patterns, are overridden. As a result, Hsieh’s performance is one of always being right on time while also becoming totally out of sync with the rest of the world.

The time-lapse film shows the hands of the clock device whirling menacingly through the abstract temporal units of hours and minutes, while the body that tries to obey the clock becomes a site that registers other kinds of times. We see the artist’s hair grow out, and we see the enfleshed temporalities of endurance and exhaustion, as he becomes more and more pallid and bleary-eyed over the 365 days. The 133 punches that Hsieh failed to make, out of the 8760 hours that are in a year, are also a crucial component of the work, because they are the corporeal slippages where the full internalisation of clock-time is shown to be unachievable.

A coincidence: during the months when Hsieh was in his studio punching away at the time clock, Dolly Parton’s hit single 9 to 5 (1980) was saturating the airwaves. The song appeared on 9 to 5 and Odd Jobs (1980), a concept album about work which also featured covers of working class folk and country classics like Merle Travis’s “Dark as a Dungeon” (1947), a rallying song among unionized coal miners, and Woodie Guthrie’s “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)” (1948), a lament for 28 migrant farm workers who died in a plane crash while being sent from California back to Mexico (“You won’t have your names when you ride the big airplane / All they will call you will be ‘deportees’”).

The song plays through the film’s opening sequence, and right away, time is depicted as a problem. Parton apparently wrote the song while she was between takes on the set, tapping her long, acrylic nails together for the percussive clicking that runs throughout (her nails are credited as a musical instrument on the album’s liner notes). The fast clicking resembles the sound of typewriters, as well as the sound of ticking clocks—and throughout the film’s opening credits, clocks are everywhere. A montage sequence with different alarm clocks going off in the morning is followed by a series of shots of women in skirt suits and high heels, rushing through the city to make it in time to the office, while anxiously looking at their wristwatches or at the public clocks that loom over them.

Metronomes are shown ticking in unison in a shop window as commuters in the race to get to work are brought into mechanically regulated sync with each other. But time is moving too fast, and the body can’t quite keep up with it. “Pour myself a cup of ambition,” Parton sings in the opening lines; only with the buzz of caffeine will she be sped up into the time of optimized productivity. One of the women in the rush hour sequence from the film’s opening credits is shown sipping a take-away cup of ambition, but she spills it as she looks at her watch, because she’s in such a hurry.

In the office where Parton, Tomlin, and Fonda’s characters work, the struggle over time continues. One of the first things the women do once they have gotten rid of their boss and taken over the running of the workplace, is to remove the disciplinary time clock—which happens to look almost identical to the one in Hsieh’s contemporaneous One Year Performance—so that workers are no longer forced to clock in and clock out. They also install childcare facilities at the office, and introduce part-time options and greater flexibility with work hours—and all of these changes are shown to enhance workplace productivity.

In the years since, the rise of post-Fordist precarity has vastly changed the time of work. While many waged workers in the US are still brutally exploited by the mechanized clock—think of Amazon workers having to urinate in bottles while on the job, to avoid getting fired for clocking too many minutes of break time—there is also, for many, an increasing problem in the blurring of the distinction between work time and nonwork time: work becomes an all-the-time condition, for which Hsieh’s 24/7 performance of constant arrival in 1980–1981 comes to seem incredibly prescient.

To linger on this historical shift in work-time politics, I turn now, with deep sadness, to “5 to 9,” the new version of the “9 to 5” song, which Parton recorded for a Squarespace commercial that aired during the 2021 Super Bowl. Have you seen it? It’s heart wrenchingly grim. The original was crystal clear on the conditions of worker exploitation: “9 to 5, yeah, they got you where they want you . . . It’s a rich man’s game, no matter what they call it, and you spend your life puttin’ money in his wallet.” In the new version of the song, all proletarian discontent is evacuated as Parton sings a creepy ode to the contemporary gig economy, where workers clock-off from their dreary day jobs at 5 p.m., and then they work, joyously, on their entrepreneurial dreams—with their own Squarespace websites—from 5 p.m. until 9 a.m.

The original “9 to 5” lyrics were furious in their insistence that “You’re just a step on the boss-man’s ladder.” In “5 to 9,” the fury has been replaced with a cheery invitation to “be your own boss, climb your own ladder!” It’s disguised as a promise of self-empowerment, but this image of being your own ladder points to the extent to which workers have been atomized as part of an historical project that has sought to destroy all solidarity. 40 years ago, Parton’s song acknowledged that collective discontent can lead to collectivized dreams for something else: “You’re in the same boat / With a lotta your friends / Waitin’ for the day / Your ship’ll come in / And the tide’s gonna turn / An’ it’s all gonna roll your way.” Today, her song tells workers that they should be excited to let work completely saturate the hours that used to constitute nonwork time: “5 to 9, you keep working, working, working / ‘Cause it’s hustlin’ time, a whole new way to make a livin’!”

There is a cautionary tale here about what can happen when struggles to improve certain aspects of working conditions ultimately leave pro-work ideology unchallenged. Back in 1980, the flexibilization of work hours at the end of the 9 to 5 film was depicted as a win for workers, but Parton’s new “5 to 9” song tells us that discontent with the drudgery of the “nine to five” work day can be easily absorbed into the system of exploitation, so that new forms of atomized and flexibilized precarity—with the constant encroachment of work into nonwork time—can be sold back in colorful, celebratory packaging, as an image of “freedom.”

Looking back on the eight-hour movement (which the “nine to five” work day is a product of), the antiwork feminist theorist Kathi Weeks has argued that historical struggles for reduced work time have too often been divorced from a broader critique of the wage labor system. 2 In contrast with these previous struggles, Weeks outlines the possibilities of a contemporary demand for shorter working hours, without a decrease in pay, that would be rooted in antiwork politics and postwork imaginaries. Such a demand would seek not only to achieve less work time, but also to confront the racial and gendered divisions of labor, and the social organization of domestic and unwaged reproductive work, which the wage labor system has both depended on and invisibilized.

Weeks shows that previous struggles to reduce work hours have often presented the rationale that such a reduction would allow for more time to be spent with family. Wanting to distance the demand for less work from a further perpetuation of the ideology of the family, she returns to a popular slogan from the eight-hour movement which said, “Eight hours labor, eight hours rest, and eight hours for what we will.” The “what we will” displaces family duty as a core rationale for shorter work hours, allowing instead for the demand to be animated by the prospect of pleasure. Weeks also points to an interesting ambiguity in the phrase “time for what we will,” which might refer to “time for what we want” but also to “time for what we will into existence.” She writes, “is it more about getting what we wish for or about getting to exercise our will? Is it a mater of being able to chose among available pleasures and practices, or being able to constitute new ones?” 3 In the new time movement that she’s proposing, the demand would be

“for more time not only to inhabit the spaces where we now find a life outside of waged work, but also to create spaces in which to constitute new subjectivities, new work and nonwork ethics, and new practices of care and sociality.” 4

Having grown up in Taiwan, Hseih arrived in the US in 1974, when he was 24 years old. He had been working at sea on an oil tanker, and when it docked near Philadelphia, he jumped ship and took a taxi to New York. He lived for the first 14 years without legal status; as part of the undocumented immigrant labour force that the US economy has long been dependent on, he made a living by cleaning floors and washing dishes for cash in downtown restaurants—usually during “after-work” hours, while others slept.

If a pro-work ethic ends up getting snuck into the 9 to 5 film as an unquestionable given—with the workplace reforms at the end ultimately re-affirming productivist values—Hsing’s contemporaneous performance piece was far less redemptive, and far more invested in noninstrumentaliszed time. It was an enactment of punctual arrival as an emptied-out gesture, wherein the artist is always arriving on time without doing anything else in time. “It’s not the question about ‘how’ to pass the time. Just passing time. This is my philosophy,” Hsieh said in a 2017 interview. “You see, tons of talented artists out there, and I thought of myself as a talentless idiot.. but then I thought, my talent is wasting time.” 5

The Time Clock Piece was one of five year-long performance works that Hsieh completed while his existence in the US was illegalized. The final one, which he did from 1 July 1985 until 1 July 1986, involved not doing any art (“I do not do ART, not talk ART, not see ART, not read ART, not go to ART gallery and ART museum for one year. I just go on in life”). 6 After the no art piece, he embarked on a 13-year work, in which he would make art but “not show it PUBLICLY.” 7 That work ended on 31 December 1999, and since then he has stopped making art. “I don’t do art any more,” he said in a 2009 interview, “I don’t have other things to say.” Instead, he remarked, “I’m just doing life.” 8

2 Kathi Weeks, The Problem With Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics and Postwork Imaginaries (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), pp. 151–174.

3 Weeks, The Problem With Work, p. 169.

4 Weeks, The Problem With Work, p. 174.

5 KaiChieh Tu, “Doing time, passing time, wasting time: An interview with Taiwanese-American artist Tehching Hsieh,” The Theatre Times, August 2017, https://thetheatretimes.com/time-passing-time-wasting-time-interview-taiwanese-american-artist-tehching-hsieh/.

6 See Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance, 1985–1986: https://www.tehchinghsieh.net/oneyearperformance1985-1986.

7 See Tehching Hseih, 1986–1999 (Thirteen Year Plan), 1986–1999: https://www.tehchinghsieh.net/thirteenyearplan1986-1999.

8 Barry Schwabsky, “Live Work,” Frieze 126 (October 2009).

This text reworks ideas and material from presentations previously given at public events with Tehching Hsieh at the TATE Modern in 2017 and at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst in 2022. The author wishes to thank the artist, as well as the organizers and attendees of those events.

Related

In dit korte afro-futuristische verhaal, geschreven door Amiri Baraka in 1995, ontdekt een ongenaamde uitvinder een manier om terug te reizen door de tijd – door muziek. “I duwde de Anyscape in de Rhythm Spectroscopic Transformation. En toen stemde ik het af zodat Anywhereness kan worden gecombineerd met de Reappearance als muziek!” legt de uitvinder uit. “Nu voeg ik Rhythm Travel toe! Je kunt verdwijnen en verschijnen waar en wanneer die muziek speelde.”

Tijdsgebonden drag, erohistoriografia, chronomornativiteit, geilheid onder het kapitalisme, ritme, dansen en 'crip time'. Dit zijn een paar van de onderwerpen die worden genoemd in het interview met Elizabeth Freeman, queer theoreticus en auteur van de boeken Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (2010) en Beside You In Time: Sense Methods & Queer Sociabilities in the American 19th Century (2017), en Amelia Groom, co-editor van de 'No Linear Fucking Time' focus op Prospections.

Reclamations of time, geared toward community and temporally “local” orientations, animate this interview with artists and activists Black Quantum Futurism (Rasheedah Phillips and Camae Ayewa), who draw from Afrofuturism, quantum physics, and “Afrodiasporic traditions of space and time that are not locked into a calendar’s date or a clock’s time." As discussed in the interview (which first appeared in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, published by BAK and MIT Press, 2021), BQF’s recent and forthcoming projects directly challenge imperial and colonial standardizations of time.

Dit essay, oorspronkelijk gepubliceerd in het Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies, is een onderdeel van muzikant en schrijver JJJJJerme Ellis’s veelzijdige project The Clearing. Ellis beschrijft het bos en zijn open plekken als “plekken van weerstandige ‘black oralities’” en verkent hoe stotteren, Blackness en muziek kunnen figureren binnen de praktijken van het weigeren van hegemonisch tijdsbeheer, spraak en ontmoeting.

Wanneer inheemse gemeenschappen worden gevraagd om bewijs te tonen van hun traditionele connectie met hun voorouderlijke landen, respecteert wat Westerse legale instanties accepteren als documentatie niet volledig hoe stammencultuur en traditionele manieren van kennisoverdracht werken. Het onderzoeksproject en boek The Language of Secret Proof (2019), geschreven door Nina Valeria Kolowratnik, reageert op de ervaring met de productie van bewijsmateriaal van bewoners in Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico. Dit boek bevecht de omstandigheden waaronder de rechten van inheemse volken om traditioneel land te beschermen en terug te winnen worden behandeld in het wettelijk kader van de Verenigde Staten.

SEA – SHIPPING – SUN (2021) is een korte film en meditatie over maritieme handelsroutes, geregisseerd door Tiffany Sia en Yuri Pattison. De film werd opgenomen over de span van twee jaar, maar is geedit om het eruit te laten zien alsof het één dag is, van zonsopgang tot zonsondergang. De film speelt de soundtrack van scheepsberichten uit het archief van BBC Radio 4 uitzendingen. SEA – SHIPPING – SUN werd gemaakt met de intentie om de kijker slaperig of relaxed te laten voelen, en verzamelt een visie van verstrengeling. Wij worden achtergelaten met de overblijfselen van geschiedenis: een zachte, wiegende waltz over de zee.

In dit essay reageert Amelia Groom op Tehching Hsieh's werk Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981) (1980-1981), een van de stukken die te zien is als onderdeel van de tentoonstelling No Linear Fucking Time bij BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Door een lezing van het gelijktijdige anti-werk lied 9 to 5 (1980) van Dolly Parton reflecteert Groom op de historische verschuivingen in de manieren waarop werknemers werden en nog steeds worden uitgebuit door technieken van tijdsdiscipline.

Grappling with the imposed linearity of timespace as a fundamental feature of colonial violence, this essay by Promona Sengupta (also known as Captian Pro of the interspecies intergalactic FLINTAQ+ crew of the Spaceship Beben) proposes a mode of time travel that is “untethered from colonial imaginations of the traversability of time and space.” While coloniality has enforced an externalization of time and space as things outside the body, Sengupta affirms practices of relational care and survival that restore time and space as embodied realities.

Weird Times (2021) is een chapbook van 30 pagina's door kunstenaars Tiffany Sia en Yuri Pattison over de tijd aflezen en hegemonie. Het bevat Sia's schrijfwerk en beelden geselecteerd door Pattison, en geeft een korte geschiedenis weer van de ontiwkkeling van technologieën voor tijdregistratie. De klok wordt gedemonteerd als een politiek werktuig, een metronoom van dwang en een versneller van oorlogsmacht. Uit deze mechanieken verschijnen weerstandige ‘counter-tempos'.

Een online gesprek met performance kunstenaar Tehching Hsieh, schrijver Amelia Groom en schrijver en curator Adrian Heathfield, geleid door Rachael Rakes, BAK curator Public Practice, op 20 januari 2022. Het gesprek neemt Hsieh's werk als uitgangspunt voor het bespreken van onder andere perfomatieve tijd, werktijd, gaten en ritmes van uithoudingsvermogen.

The No Linear Fucking Time Bibliografie is een zich ontwikkelend naslagwerk waarin wetenschappelijke en artistieke teksten worden gebundeld die betrekking hebben op de verscheidene onderzoekslijnen binnen dit project.

In ‘Reclaiming Time: On Blackness and Landscape’ (voor het eerst gepubliceerd in PN Review issue 257 in 2021), bekijkt dichter en schrijver Jason Allen-Paisant de geracialiseerde maatschappelijke contexten en moderne milieuconstructen die ‘Zwarte levens disproportioneel beroven van de voordelen van tijd.’ Hij put uit zijn poëziebundel Thinking with Trees om een koloniale epistemologie van de natuur te schetsen, en de rol van poëzie te benadrukken in het genereren van vormen van Zwart verwantschap en politiek bewustzijn, gebaseerd op een hernieuwd gevoel van ‘diepe tijd’. De vraag of het mogelijk is om middels poëzie ‘tijd terug te claimen’ staat centraal in de tekst.

Als hij door de ‘Nothing To Declare’ uitgang van het vliegveld London Stansted loopt, ziet Sam Keogh drie grensbewakers: een varken, een eenhoorn en een bezorgde cartoonklok. Pig Eater is het script voor een monoloog dat voor het eerst opgevoerd werd als onderdeel van Keogh’s tentoonstelling Sated Soldier, Sated Peasant, Sated Scribe, in Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, Londen in 2021. Het verweeft fantasieën over overvloed en de afschaffing van werk; over feesten en rusten; over sabotage, anachronisme en het ‘opfokken’ van lineaire tijd.

In dit gesprek met Walidah Imarisha (voor het eerst gepubliceerd in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, BAK en MIT Press, 2021), schetst de schrijver en activist haar concept van ‘visionaire fictie’ als een verbeeldingspraktijk om toekomsten te verlossen van het bolwerk van lineaire tijd. Imarisha put uit haar werk als strafrechtelijk abolitionist, en spreekt specifiek tot de bewegingen en ideeën die voortkomen uit de Zwarte strijd in de Verenigde Staten. Ze benadrukt dat we ons bij het veranderen van de toekomst moeten verhouden tot het verleden: ‘specifiek vanuit een kader gericht op gedekoloniseerde, niet-lineaire dromen van vrijheid die gegrond zijn in de strijd van gemeenschappen van kleur voor autonomie en bevrijding van kolonialisme.’

In haar essay ‘In Some Places the Not-Yet Has Long Been Already’ (voor het eerst gepubliceerd in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, uitgegeven door BAK, basis voor actuele kunst en MIT Press, 2021) put Elizabeth A. Povinelli uit haar werk als onderdeel van het Karrabing Film Collective. In de tekst contrasteert ze de temporele oriëntatie van het laat-koloniale liberalisme – getroebleerd door de op handen zijnde catastrofes van een totale klimaatinstorting – met de voorouderlijke catastrofes van kolonialiteit en slavernij, die zowel van het verleden als het heden zijn. Deze voorouderlijke catastrofes, aldus Povinelli, ‘blijven groeien uit de grond die kolonialisme en racisme hebben bewerkt, in plaats van op te duiken aan de horizon van liberale vooruitgang.’

‘Dysfluent Waters’ is onderdeel van het multidimensionale project The Clearing van muzikant en schrijver JJJJJerome Ellis, respectievelijk een boek uitgegeven door Wendy’s Subway en een gelijknamig album uitgebracht door NNA Tapes in 2021. Hij ziet het bos en haar open plekken als ‘plaatsen waar al eeuwenlang verzet plaatsvindt middels zwarte gesproken cultuur.’ Ellis onderzoekt hoe stotteren, zwartheid, en muziek een rol kunnen spelen bij verzetspraktijken tegen dominante voorschriften voor de beleving van tijd, spraak en ontmoeting.

In haar tekst ‘Dearest Zen (Letters to Lichen)’ presenteert kunstenaar en wetenschapper Adriana Knouf toekomstige liefdesbrieven aan korstmossen: de samengestelde symbioten van schimmels en algen of cyanobacterieën. Bezien door de lenzen van de ‘xenologie’ (Knouf’s term voor de studie, analyse en ontwikkeling van het vreemde, buitenaardse en andere) en trans*-tijdelijkheden, onderzoekt ze manieren om te leren van, en opgetogen mee te doen met, intimiteiten en uitwisselingen tussen verschillende organismen.

In ‘Immortals: on the Ancient Future Lives of Stone and Plastic’ verweeft Marianne Shaneen verhalen, geschiedenissen en ontologieën van twee materialen: steen en plastic. Als quasi-onsterfelijke substanties zijn steen en plastic getuige van de catastrofale effecten van uitbuitende lineariteit, terwijl hun levensloop veel langer is dan dat van een mensenleven. Dit essay verweeft deze twee materialen, die schommelen tussen het geologische en synthetische, en die diep ingebed zijn in industrieel-kapitalistische ontwikkeling.

‘The Clearing: Melismatic Palimpsest’ is onderdeel van het multidimensionale project The Clearing van muzikant en schrijver JJJJJerome Ellis, respectievelijk een boek uitgegeven door Wendy’s Subway en een gelijknamig album uitgebracht door NNA Tapes in 2021. Hij ziet het bos en haar open plekken als ‘plaatsen waar al eeuwenlang verzet plaatsvindt middels zwarte gesproken cultuur.’ Ellis onderzoekt hoe stotteren, zwartheid, en muziek een rol kunnen spelen bij verzetspraktijken tegen dominante voorschriften voor de beleving van tijd, spraak en ontmoeting.