On Housing Struggles in the Netherlands

Author(s)

Here to Support, Amsterdam University College Rent Strike, Bond Precaire Woonvormen

Interview en introductie door Irene Calabuch Mirón en Sanne Karssenberg (BAK, basis voor actuele kunst).

In this context, in the Netherlands and many places throughout the world, collective responses are coalescing—in the forms of rent strikes to neighborhood-based mutual aid, among other things—with both immediate survival and long-term change in mind. In the case of the Netherlands, several movements and organizations focused on urban struggle and housing emergency are adapting their existing practices, or creating new ones altogether, to address these urgencies. In this conversation, three groups engaged in the housing struggles report on their current activities and share their insights on how to respond to mounting housing emergencies.

HERE TO SUPPORT

Here to Support is an organization that provides practical, political, and social resources for undocumented refugees in limbo in Amsterdam. Here to Support organizes local and international meetings and events, and engages in various creative and advocacy projects aimed at growing and strengthening networks with and for undocumented people.

Many of your cultural and educational activities had to stop due to the Covid-19 emergency. What is your focus at the moment? How are you organizing and what are the priorities?

All our activities, from regular events and workshops to international projects such as City Rights United—which brings activists and organizations in Europe together in the joint struggle to realize human rights for undocumented citizens—are temporarily on hold. Our main concern at the moment is finding a solution for the big groups of people in extremely vulnerable positions that have no place to stay during this crisis. All-day shelters shut their doors due to the pandemic, so homeless people in Amsterdam were forced to stay on the streets during the day. There were two or three days in which they did not have a place to go to the toilet, drink water, etc. They had to stay in parks.

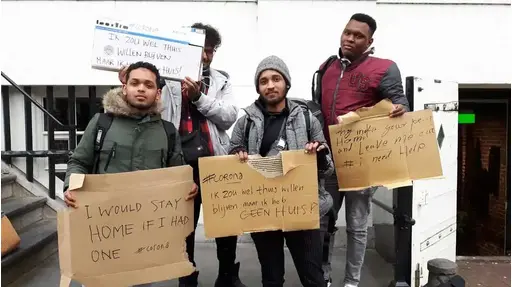

In order to find a solution to the lack of day shelters, we used social media to ask several venues in the city to open their doors and host those who did not have a place to stay. We also asked for donations for food and drinks that would normally be provided by the shelters. Trying to visibilize the situation, we started a Facebook campaign with pictures in which undocumented migrants ask for a place to “be home” and be safe. The slogan is “I would stay home if I had one.” As a consequence of this call, we started collaborating with different organizations and setting up day shelters in two locations in the city. These facilities are now running, providing basic needs and safety.

However, we are still working on better solutions. At the moment, the group of undocumented migrants that we normally support is staying in an emergency night shelter, organized by the municipality in collaboration with big NGOs (Red Cross, HVO Querido, and Salvation Army). So their condition is still precarious and unstable.

How is the health crisis affecting the process of setting up these shelters?

When a shelter is set up, it needs to be checked and approved by the GGD (Dutch health organization). They give us tips on how to improve and adapt the conditions, mostly on hygiene, so the facilities are as safe as possible. If someone gets sick, they leave the shelter and are taken into a quarantaine area set up by the municipality.

However, the problem while setting up these shelters is that, because we take the rules about physical distancing very seriously, we cannot shelter more people than we do now: the capacity of the facilities is less than usual due to the “1,5-meter economy.” This means that the shelters are for smaller groups, which is the reason why opening more venues to host more people is very important.

What are your next steps? Now that some of your first and most pressing demands are being met, do you see openings for more durable change after the heat of the crisis is over?

We are asking the municipality to provide all-day, 24-hour shelters. This demand has not been met yet, but we are currently cooperating with the municipality and various NGOs to organize this.

Though not having a place to stay is a major issue for a lot of migrants at the moment, it is important not to forget that they are not only dealing with a housing problem, but with the failure of migration politics that puts them in these vulnerable positions in our cities. They don’t have medical insurance or any kind of social security, nor the physical structure to protect themselves. We think that Covid-19 makes it clear that everyone needs basic facilities, that no one can live without “bed, bad en brood” and protection. When a disaster like this strikes, it is made evident that people do not choose to be homeless, which seems to be an extended belief. People can’t protect themselves without basic sheltering for day and night and a well-functioning care system.

Covid-19 exposes the inhumane conditions that many migrants are forced to live in— conditions that, according to most of our current politicians, are “good enough.” We hope that from now on, in every discussion about migrants sheltering, whether in city buildings or refugee camps, people will ask themselves: what if a pandemic will hit again?

[i]If people want to join or support your movement, how can they do that?

You can find out how to support us by subscribing to our newsletter, which will keep you informed about our activities and announce our campaigns. Also, you can support us by donating here.

AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY COLLEGE RENT STRIKE

Amsterdam University College (AUC) Rent Strike is a student group formed at Amsterdam University College that aims to mobilize students into a mass rent strike. The group was born as a response to the lack of effective measures to protect the living conditions of the student population during the Covid-19 crisis.

How did you come together as a group and how are you organizing at the moment? What are the lessons and challenges so far?

Due to the restrictions put in place to fight the pandemic, many students have lost their sources of income overnight, as did many people across Amsterdam, the Netherlands, Europe, and the rest of the world. Here in the Netherlands, the closure of the catering industry has cost many students their financial security, and there are not any policies or initiatives directed at helping this group. The measures provided by our university, the Amsterdam University College, and DUWO, the housing corporation that rents out the buildings, are proving to be insufficient. We came together to mitigate the effects of this crisis on our student community and fight for more effective measures.

We started as a small focus group of AUC students. Some of us were directly unable to pay our rent, and others recognized that solidarity is necessary to implement real change. Due to the immediacy of this issue, we started to brainstorm together to come up with a response to this urgent situation. As a result of this brainstorming, we decided to organize a rent strike.

We started organizing within our own housing building, as well as reaching out to other buildings to build a stronger group. So far, what is difficult is convincing people who can pay their rent, not to, for the sake of solidarity. At our university many people can afford it, so they don’t see the point in not doing so. Also, many students have the idea that not paying rent could hurt DUWO employees, and therefore we should stand in solidarity with them and not cause any trouble. When dealing with this perspective, we try to be very clear and explain the real consequences of a rent strike, and to express that it’s important to support fellow renters instead of big corporations like DUWO that are profiting on tenants. What works is giving very clear explanations, and being as transparent and open as possible whilst trying to remain anonymous. Further, it is critical to continue bringing in examples of rent strikes taking place in other countries that inspire us, and show that a rent strike is an organized methodology of resistance rather than an over-the-top reaction.

However, physical distancing makes connecting more difficult. It is hard to gain mass for the strike, because many tenants in our building have returned home. Not being able to have larger gatherings now—and possibly not in the coming future—where people can chat with us and get to know each other makes it more difficult to build a sense of community with the strikers.

You mention that the measures being taken in order to protect precarious students in this time of crisis are insufficient. What measures are in place at the moment and what do you demand instead?

We articulated some demands in relation to the measures in place, that are as follows:

Even if our efforts to make DUWO meet our demands are currently focused on our university buildings, we hope that creating this platform will also help to fight housing injustices in other parts of the Netherlands. Being such a new initiative, we are now focused on projecting our demands out into the world, and gaining attention and support to accelerate the initiative itself and involve more people. However, this experience is showing us that it’s impossible to ignore the larger speculative systems at play—ideological, political, economic, etc.—that have led to this issue in the first place. Ideally, our demands would be met by DUWO and considered for all tenants across the Netherlands.

We also question and challenge the government’s decision to help (or “bail out,” rather) large corporations like DUWO before considering helping the people. We hope that our rent strike is seen as a collective action against DUWO’s exploitative policies. If our first set of demands are met, we would seek advice from our network to develop a new plan for how to bring this issue to wider attention.

What would be the positive consequences of this strike for you, students, but possibly also for other groups of renters?

The most positive outcome of our strike would be that our demands are met. Rent would be fully suspended for all DUWO tenants; there would be no evictions (even after the first deadline instated by the government passes); and tenants who have fled the country would be able to open up their rooms (at their own discretion) to non-students who have been displaced by the pandemic (of course, without fee). Moreover, we truly believe that if we are successful, our strike could be used in the negotiation regarding the pitfalls within the housing system in Amsterdam and across the Netherlands.

The government’s no-eviction policy, as of now, is only in place until 1 June 2020. After then, tenants who did not pay rent during the crisis will have one month to pay for all of the months they didn’t. This is a tricky situation, but also one of the reasons we need our more financially-stable peers to strike with us. Another issue raised is the state of the economy, and how a country-wide strike would affect the economic situation of DUWO and perhaps other rental companies. To that we respond simply: if this pandemic has shown us anything, it is that the neoliberal-capitalist structure of our society, and especially the housing system in the Netherlands, is incapable of protecting the people in crisis. If the system isn’t challenged, nothing will ever change.

You mentioned that you are in contact with other organizations and collectives that support your struggle. Which organizations are you in contact with and how do these relations work?

We used our personal networks of people in collectives to get support and connect with people in other DUWO buildings. Besides, we connected with groups working on housing and student rights such as Vrije Bond, Bond Precaire Woonvormen, and Revolutionaire Eenheid. These collaborations give us more insight into the mechanisms of the Dutch housing market and how the state deals with housing protests. Further, working with groups that have a better understanding than we do of Amsterdam politics helps us to see the bigger picture of where we fit into the general housing struggle in the Netherlands. In the long term, collaborating with other collectives strengthens the strike and helps us to politicize our message more and reach a wider audience since our networks are limited to primarily students.

If people want to join or support your movement, how can they do that?

If you would like to get in touch with us to join or support the strike, you can do that at ams_rent-strike@protonmail.com. You can also follow our Instagram account, @AUC_rentstrike.

At the moment we need more publicity and media attention. It’s important to reach as many people as we can, within our DUWO dorms at AUC and those residing in other DUWO buildings across Amsterdam and the Netherlands. There really is strength in numbers, and if we can expose our initiative to more DUWO tenants, we hope to inspire more people to join us.

BOND PRECAIRE WOONVORMEN

Bond Precaire Woonvormen (BPW) is a social movement that protects housing rights in the Netherlands, supporting tenants through legal and social means.

How has the Covid-19 affected your usual activities? How are you using your organizational structure to support tenants in this time of crisis?

During this crisis, temporary tenants and people living in antikraak (vacant properties temporarily rented to prevent squatting) are still being evicted. More tenants are contacting us about their evictions now that coronavirus has made their situation more problematic and precarious. On a policy level, we try to influence the measures established during the pandemic by being in contact with politicians that are willing to bring questions about housing rights to the Dutch Parliament. But mostly, we are trying to support tenants in many ways with our already-existing infrastructure and contacts. We try to share our knowledge as much as possible in order to empower a tenant movement from below that is able to crush the status quo with solidarity and will.

Going into concrete practices, since a lot of people in need of help at the moment are not fluent in Dutch, we made this English brochure to make information about their housing rights and how to connect with other tenants. We also try to visibilize the situations of the people that contact us by spreading their stories through the national network of BPW and social media of tenants, and we are in contact with journalists of local and national media to write and produce TV programs. As an example, we are currently engaged on an online campaign with Ehsan, a tenant with a flexible contract in Amsterdam, who was threatened with eviction. So far his eviction got postponed, but his housing situation is still unstable. We are also helping with the organization around a neighborhood in The Hague, and supporting the AUC Rent Strike.

While we deal with the emergency, we also try to prevent regular housing abuses that will have an amplified effect in these conditions. Even if a lot of tenants are in precarious positions due to Covid-19, the government and landlords will go ahead with the yearly increase of rents, scheduled for 1 July 2020: while last year the increase was of 5,1%, this year it will be of 6,6%. We are preparing a standard letter that tenants could send before 1 May to ask to lower the rent. However, letters will probably need to be accompanied with collective direct action.

We will see what all of this will bring. For now, digital struggles. Later, the streets.

Have your usual demands changed in this situation of emergency? Could the urgencies of today open the door for more structural and lasting changes?

Some of our demands have indeed been slightly modified during this crisis, but mostly our long-standing demands have become more relevant due to the emergency. Taking that into consideration, we launched a petition with our most pressing requests that you can check here. Our four main calls are:

We hope that these demands will also have an impact in the long term. However, we know that we cannot fully rely on the Dutch government to meet the demands: we need a strong social movement pushing for them. These days, discussions about temporary housing measures to deal with the crisis are taking place in the Dutch Parliament, and the opposition is proposing a rent freeze and to stop evictions during the lockdown. However, nothing concrete came out of it so far, and in our experience, it hardly will. Now more than ever, we need solidarity to fight for decent housing with affordable rent, rent price protection, and security of tenure.

The positive thing about this situation is that we see that different groups are building new alliances and working together because of the crisis. Even with social distancing measures in place, we are finding out that mutual aid and cooperation is still possible. It also shows that solidarity can cross streets, neighborhoods, cities, and even countries. That gives us a sense of hope.

If people want to join or support your movement, how can they do that? Where is help needed?

If you need help, or have a question as a tenant and want to organize with us: https://bondprecairewoonvormen.nl/vragenformulier-tijdelijke-bewoners/

If you want to become a member of BPW, join us here: https://bondprecairewoonvormen.nl/steundebpw-2/

“[i]Bed, bad en brood” (Bed, bath, and bread) is a measure that provides temporary basic care for undocumented migrants and rejected asylum seekers, in exchange for their cooperation to return to their “home country.” In 2014, the European Committee of Social Rights determined that the Netherlands violated the European Social Charter by not providing assistance to rejected asylum seekers. This generated an intense debate in the Dutch Parliament in which the need to provide basic requirements to rejected asylum seekers was questioned. The discussion was settled with the “bed, bad en brood” agreement, which is often criticized by asylum seekers and allies.

Related

BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht stands in solidarity with the Palestinian decolonization struggle and with decolonization efforts everywhere.

Deze lokaal georiënteerde tweede editie van Practicing Tactical Solidarities, op 16 december 2020, richtte zich op verschillende tactieken en mogelijke lessen op het gebied van het creëren van netwerken voor wederzijdse hulp, duurzame ondersteuningssystemen en spoedeisende zorg tijdens de aanhoudende pandemie.

La Colonie opened its doors on rue La Fayette, Paris on 17 October 2016 as a radically open space of discussion and exchange for diverse cultural and political communities.

Voor deze eerste sessie van In Proximity, een doorlopende serie als onderdeel van Prospections, gaat Rachael Rakes, curator Public Practice bij BAK, basis voor actuele kunst in gesprek met kunstenaar en BAK 2017/2018 Fellow Wendelien van Oldenborgh.

Een videoregistratie van het online event Practicing Tactical Solidarities: A Roundtable on Mutual Aid, Emergency, and Continuous Care, gelivestreamed via Prospections op woensdag 29 april 2020, 19.00–21.00 uur.

Interview en introductie door Irene Calabuch Mirón en Sanne Karssenberg (BAK, basis voor actuele kunst).

Uit: Trainings for the Not-Yet, een tentoonstelling als een serie trainingen, door Jeanne van Heeswijk en BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht in samenwerking met vele anderen (2019–2020)

Voortgekomen uit: New World Academy, een alternatief educatieplatform voor kunst en politiek, opgezet door Jonas Staal en BAK, basis voor actuele kunst (2013–2016).

Uit FORMER WEST: Art and the Contemporary After 1989, Maria Hlavajova en Simon Sheikh, eds. (Utrecht: BAK, basis voor actuele kunst en Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), pp. 379-390.