Interview

Author(s)

Kader Attia, Marion von Osten

Uit: Once We Were Artists, Maria Hlavajova and Tom Holert, eds. (Utrecht: BAK, basis voor actuele kunst en Amsterdam: Valiz, 2017), pp. 32–52

Kader Attia and Marion von Osten: Interview

Kader Attia: This conversation could begin on an American road between Los Angeles and San Antonio. You know, the endless roads scattered with old cheap motels, like the ghosts of the modern dream designed in 1950s aesthetics and acting as a link to a so-called era of great progress. Back when the west was a symbol of conquest, and capitalism was an

ideal . . .

I thought about you when I was in San Antonio. I visited several seventeenth-century Spanish Christian missions, or rather what was left of them. Most of these beautiful architectures can easily be compared to any Mediterranean Christian architecture. If you remember that Spain had been colonized by Muslims for five centuries, you can see and understand better how Spanish colonial style took root in America thanks to characteristic Arabian-Muslim vernacular architecture. This brings up my first question to you, instigator of the amazing project In the Desert of Modernity: Colonial Planning and After (2008–2009): Is colonialism responsible for the evolution of architecture through and toward a modern agenda?

Marion von Osten: Historically speaking, the purpose of any colonial plan was to create new settlements and to bring new housing solutions for a distinct non-indigenous population arriving from some other part of the world. When I say “distinct,” I mean separated. These constructions were created for colonists—colonial settlers—and separated them from other, already existing habitations and social communities. The colonial settlement is thus a biopolitical entity, a satellite community in a partially unfamiliar area and one that does not want to mingle. But as it has been proved, this will to segregate itself from the local environment always fails. In relation to your comment about Spanish missions, I just visited the historical Franciscan missions in California, where I learned that the church and cloister in Santa Barbara, for example, were built by local Comanche tribes.

This is important, for the Franciscan monks would not have survived without the Comanche, as the latter fed them when they arrived in the eighteenth century. Also, the First Nations handled the construction of the cloister, church, and houses while teaching the monks how to craft textiles and pottery. After the mission was established, the natives were given free food and Christian education as a reward for their labor. Here it becomes interesting because, even though their survival was completely dependent on the Comanche’s local knowledge and food, the monks assumed native people to be naive people who needed education and to be taken care of. This is what makes any colonial civilizing mission so paradoxical, as it depends on local people’s knowledge, yet it does not acknowledge them as de jure subjects. This is also expressed in architecture. You can find some transcultural translations in these specific places. The church design is based on drawings from Vitruvius’s famous architecture book from ancient Rome. However, the monks only followed Virtruvius’s model of a Roman temple because they had no other example. Plus, in this strange church-temple you can find small transpositions of Comanche ornaments on the ceiling and Mexican figurative elements beside paintings with belated baroque aesthetics. This eclecticism or conscious or unconscious translation—praised as California’s multicultural heritage—conceals that Christian and Roman aesthetic traditions remained hegemonic, while other transcultural elements remained marginal. This hierarchy in the use of aesthetics is mostly expressed in the settlement designed by monks for First Nations converts. The Comanche housing facility next to the cloister showed very modern lines; it was designed like a camp built in a grid-like structure. This small-scale housing grid, specifically created for the natives, echoes philosopher Jacques Rancière’s words about distributing the sensible 1 and, therefore, about domination.

Even when we need to constantly highlight transfers and exchanges created through specific cross-continental encounters like between the Comanche and Franciscans, as they later became a particular Christian group following early communist ideals, architecture still reveals this hierarchy and dominance that denied the Comanche’s rights to be represented as gifted fishers, sailors, and farmers or as spiritual collaborators, political allies, or even fighters. When the economic and military interests of Spain, Russia, the Mexican Empire, and, later, the United States caused never-ending conflicts on this territory, the first to suffer abuses and die were the Comanche.

And there, again, what is striking is the specific rationality in the Comanche settlement from the Santa Barbara mission, for it consequently used this same grid pattern. The grid, as a planning principle, is to be found in the organization of most colonial processes. It already existed during the Roman Empire, so in the end, Spain was not the first one to use it. This grid structure is an artificial and rational pattern free from any context and can be expanded any time. It is about expansion, identifying and conquering new territories in any part of the world. It is about housing a great number of people, about future population growth, since the grid can easily spread into any direction. It is also the same pattern as the famous Philadelphia grid developed during the eighteenth century, and yet when you come to studying colonial cities, you realize it had already been adopted for years in each and every one of them. A village or town based on this structure is the very basis for creating any new artificial site or, just like in Caracas, for example, a colonial town similar to many other places you might add to your own research. New town planning and the grid structure that are nowadays perceived as high modernist aesthetic items were brought into building practices and modern discourse through colonial expansion.

KA: Your answer reminds me of how Spanish Emperor Carlos Quinto ordered Mexico’s city planning, following a parallel and perpendicular street pattern. And do you know why? To have control over the population. When Tenochtitlan was taken over by the Spanish they decided to slowly develop their new city on top of the former Aztec capital. These days, some architecture from these colonial settlement projects, such as the Catedral del Zócalo, are slowly falling down because of the old Aztec temples underneath. These “conscious and unconscious forms of cultural translations” seem to be another kind of “repairing,” because they act as endless cultural translations from one cultural space/time to another. To come back to this colonial settlement planning and to why it reminds me of the first urban plans in Mexico during the early sixteenth century that aimed at controlling people, do you sometimes think that architecture consists of filling a given space, while actually it is the contrary, thus making urban plans more important than the buildings themselves in the end? Do you think that projects led by you and me, among others, like the architect and urban planner Michel Écochard in Casablanca, aim at controlling people through some vertical panopticon or, on the contrary, providing intimate spaces for the inhabitants? And eventually, what drew them to totally close their own balconies?

MvO: Yes, I think you are right, colonial settlement is mainly about organization and urban landscaping, but not so much about establishing an individual house for one particular settler. Biopolitical implications are quite obvious when we think of them as closed entities. What most people ignore, as your question pointed out, is that this vision of colonial planning has considerably influenced modern building concepts like, for instance, city planner Ebenezer Howard’s famous garden city. A book entitled A View of the Art of Colonization: In Letters Between a Statesman and a Colonist (1849), edited and co-written by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, which also served as propaganda to convince the British government to build a settlers’ colony in New Zealand, mainly influenced Howard’s concept. But the latter’s goal with the garden city that actually started his career in the US before being published in the United Kingdom went even further than its colonial blueprint. The idea was to sustain, through a satellite city concept, “a healthy, natural, and economic combination of town and country life” 2 thanks to balanced working and relaxing times. This concept aimed at getting away from the contentious relations between industrialization and countryside. Just like in future replicas of the garden city—such as the satellite city or the cité nouvelle—life, production, and education were strongly connected. Moreover, spatial organization of confined islands, segregated from the heart of the city and from other social groups, must have been based around new ideas about labor conditions and accumulating wealth as well. In Howard’s original vision of a confined settlement, discipline and control were obviously part of the strategy. It is also strongly related to hygienic and epidemic argumentations. Only later was consumption added to the garden-city movement, following new town-planning systems created in the twentieth century. From then on, the new town emerged not as a sign of total enclosure, but as a place that was organized from A to Z. The principle of neighborhood units also appeared there and then developed in the US with urban planner Clarence Stein.

When living in Casablanca under French protectorate, Marshal of France and colonial administrator Louis Hubert Gonzalves Lyautey followed ideas close to Northern American industrial development plans and Howard’s garden city concept in his vision of the European colonial town, Casablanca. This concept, first introduced in European cities, was later used as a strategy to shut the local community out of the center when building what they called the Habous neighborhood or the new medina. Later on in the 1940s, Verlieer, a French town planner and socialist, appropriated the garden-city model again in his new planning of the huge Aïn Chock settlement, a fantasy of a Moroccan village using the grid plan; local workers then lived far away from the heart of Casablanca. A few years later, Écochard established a housing grid for his constructions—applying the “Housing for the Greatest Number” principle—because of the increasing number of colonial factories or even service workers. This housing grid, as the main instrument for new urban neighborhoods, was also meant to replace the numerous slums from the late 1940s to the mid-1950s that were mostly inhabited by rural migrants. In fact, the large-scale housing programs were the French protectorate’s attempts to build modern settlements for the colonized just when anti-colonial uprising emerged as Morocco obtained independence in 1956. In those times of resistance, the French urban planning services strategies varied from reordering the slums (restructuration) to temporary re-housing (relogement) while also creating new housing estates with controlled rents (habitations à loyer modéré), all according to Écochard’s grid. His master plan applied notions of “culturally specific” housing, making—according to his vision—local construction practices the starting point for developing a variety of housing typologies adapted to each category of inhabitants. These categories were still confined to already existing definitions of cultural and racial differences. However, it was only under colonial rules that categorization reinforced and was turned into a means of exercising governmental power. Écochard’s plan divided the city into different residential zones for European, Moroccan, and Jewish residents, as well as industrial and trading areas.

Only “Muslim” housing estates were built far from the “European” colonial city by creating a so-called zone sanitaire (sanitary zone), the boundaries of which were actually the newly built motorway. This spatial separation was also inherited from the colonial apartheid regime during which Moroccans were forbidden from entering the protectorate city unless employed as domestic servants in European households, and, likewise, that constituted a strategic measure, facilitating military operations against any possible resistance.

KA: Do you remember, Marion, how we first met many years ago? I think it was for a video work called Normal City (2003) (depicting social building facades from my teenage years in Paris’s suburbs). Could you find a link between European western or eastern social architecture aesthetics and what has been functionally experimented as a modern housing ideal for the native people and “adapted” in former colonial areas (during pre-independence times)? Again, I am thinking about Écochard in Morocco or architect Fernand Pouillon in Algeria, who apparently tried to adapt their designs to local indoor and outdoor living traditions. I always have the feeling that it is only possible to live in (not to say survive) such a neighborhood, just like in millions of other social housing blocks built for immigrants in the west, because the inhabitants re-created a social structure identical to those of the villages most of them came from. Everyone knows each other and says hello, and if something wrong is about to happen, someone can see it from their window and, for instance, advise you to remove the bag you forgot in your car or park it in another place so that you can keep an eye on it. So, again, here is my question: How do you deal with this dialectic between social housing aesthetics and ethics, this complementarity of minimal functionality and aesthetics? Does it make sense to you? Does this aesthetics fit its own time, which was considered “nice” or stark on the contrary?

And last but not least, could this aesthetics have been part of the control project that happened through standardization of the subjects (the inhabitants) as the objects of the modern social order . . . ?

MvO: I think you are right in both cases, since the modernist project was and is about ambivalences, on the one hand, to grant people with a better life but, on the other, to control and educate them. The Écochard grid was dimensioned according to a typology of houses with courtyards believed to be appropriate for future inhabitants who will live in slums. His so-called culturally specific “Housing Grid for Muslims” measured eight meters by eight and consisted of two rooms and a wide outdoor space related to Arabic patios. Part of the ensuing 64 m2 was organized as a so-called neighborhood unit resulting in an intricate, ground-level structure of patio houses, alleys, and public squares. A single house in this grid consisted of two or three rooms and a patio by way of entrance. Using a variety of combinations, it was designed to be flexible enough to eventually adapt to creations seen in other housing types (individual or collective), states the architectural historian Catherine Blain. The patio house in Écochard’s vision allowed “growth” through usage. As psychologist Monique Eleb stated during the conference “The Colonial Modern” at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin—which you attended in 2008—the patio reference was not a copy of a traditional courtyard house but a European (mis)interpretation. On the other hand, the patio house structure developed in French colonies should be understood as a modernist synthesis, a Eurocentric translation that also carried pedagogical intentions to teach people modern industrial production and consumerism.

Though housing programs in French colonies from the 1950s/1960s did take certain specific local, regional, or cultural decolonization these conditions turned out to be much more complex than originally thought. The single-floor, mass-built modernist patio houses, intended to facilitate control over Moroccan workers, are now so altered that one can no longer distinguish their original base structures. The builders simply used the base of the original design and foundations to construct three- or four-floor apartments. The many ways of appropriating space and architecture by people can also lead to assume that neither colonialism nor postcolonial governments ever managed to establish complete control over the populations.

KA: I agree, and it sounds very interesting, as an investigation process, to reveal how and why reappropriation emerges. As far as I am concerned, it took me years of thinking to be able to observe early “signs of reappropriation,” from architecture to any items, even human behaviors. Rancière offered an interesting analysis in The Emancipated Spectator, 3 which is a reference to another article called “Le Tocsin des travailleurs” (The Tocsin of Workers), published in the nineteenth century in an old French union newspaper. . . . To sum it up, the article describes a worker cleaning the wooden floor in a bourgeois house, removing the old surface with a large blade (tough job). After long hours of efforts, he decides to stand up and then looks out the window. He slowly ends up appreciating the view, as well as the perspective leading to the horizon of French “classic” gardens. The pleasure he takes there makes him dream of how he would set up all the furniture in this room, just like he would at home, following his own tastes to decide the kind of furniture he would buy, as well as where and why he would put a given item in a given place, etc.

Rancière explains how, from bending on the floor and working hard to standing up in order to stretch a bit and look out the window, the worker switches from one state to another: from “the manual state” to the “visual state.” At this very moment, he stops being only hands executing orders so as to “reappropriate” his own self by watching and coming up with his own conclusions. From the hands to the eyes, his individuality reappropriates its freedom by reappropriating the perspective his social position has shut him out of and from which his eyes had been taken off. Founder of mutualist philosophy Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was the first to highlight “reappropriation.” Remember his “property is theft”? 4 It also meant social struggle is a reappropriation of what has been dispossessed by the bourgeois and bureaucratic system . . .

Another personality you made me discover in one of your essays, “Architecture Without Architects—Another Anarchist Approach,” published in e-flux journal, issue no. 6, in 2009, is the British anarchist and architect Mark Crinson (perhaps you did it on purpose). The questions such an interesting political figure and personality raises within the understanding of contemporary social architecture are in the continuity of Proudhon’s thought. I would definitely compare him to Paul Robeson, a multitalented personality. This African-American former athlete, who was physically impressive due to his height and voice, was an actor, a singer, and an active communist. In a movie, I saw him sing the Chinese national anthem on a stage right in the middle of the street! The notion of cliché might not exist in human nature; it is probably a product of the modern mind as a consequence of rationalism based on two obsessions: measuring the world with classification (through categories) of things and the fantasy of progress as a pure sign of evolution.

Philosopher and literary critic Edward Said has beautifully summarized the relationship between anarchism and architecture through the western cliché of Orient with his recognition that the Orient has been Orientalized by Occident. It sounds like a legacy of the western desire to control otherness, first culturally, then politically.

The way windows and balconies were arranged in so many social housing buildings designed by European minds in non-western, colonized contexts from Asia to North Africa (in Casablanca, for instance) raises two questions. If these transformations of balconies into kitchens or closed, inward facing rooms are “reappropriations,” then what about freedom? In the cité verticale, why have all the large and comfortable balconies, which aimed at opening each apartment to the outside so as to take advantage of both public and private spaces at the same time just like a private courtyard, been covered and closed by the inhabitants? Was it for self-protection, for moral issues (which are linked to Islam and privacy) in response to a design generated by another culture from another time, the culture of colonial domination imposing its utopian vision on another culture?

Could we say that adding confinement to these constructions is a “reappropriation”? When in Arabian Berber Muslim culture, domestic privacy cuts women off from outside eyes so there is no way to see their faces and bodies in their private apartment, could we say that the modern European architecture gender issue failed here? Or as Said investigates in his essay Orientalism, 5 is it a purely western fantasy to think it is easy to reach Muslim Arabian women?

I am sure you have seen examples of these thousands of old colonial postcards representing such “western fantasies,” like half-naked women in their apartments . . .

MvO: I vaguely remember an article about veiling in North Africa, stating the first forms of veiling noticed by natives were English ladies covering themselves from the sun and sand. And the author then highlighted the invention of sunglasses with which you can look around even though no one can know what you are looking at, since your eyes cannot be seen. So, I have no answer to your last questions, but perhaps some more comments on your first one that might lead to a whole set of future investigations on what we like to call production and what is called appropriation.

There is a concern about the use of the word appropriation and its concept: in it sleeps the very notion of property, as you pointed out when you quoted Rancière. The concept of appropriation thus suggests that something used to belong to something/somebody and was later developed by somebody or/and used in another geographical context or fashion. This concept suggests no original articulation in itself. Notions such as copy, imitation, and appropriation deny any immediate emergence, yet in the meantime, this emergence is claimed by western modernists, like the architects we were talking about. In the last decades of cultural anthropology and postcolonial thinking, appropriation was used to mark tactics and strategies in a de Certeauian sense, I believe, to show that programs and concepts from above can be altered and subverted from below. But somehow it also suggests that there would be no “first” voicing, but always a belated reaction, only existing because there already was a first voicing by somebody else. The problem I have started to have with this concept is that it is mainly used for describing social class relations or in non-European articulations. When you talk about reappropriation, it aims at making this all a bit more complicated, since it is not clear who a concept and idea originally belonged to. And, as I discuss it in my own research, this is also true about modernism, as it can only be understood as a constant translation or synthesis of vernacular practices into a more rationalizing and universalizing concept that was later called modern. Still, it was a concept that appropriated the Arabian kasbah, the Indian bungalow, the courtyard house, arts and crafting from the colonies, etc. According to this, it escaped the classical and renaissance past, but in the same way the classical era claimed to have higher taste and value, to be more civilized and universal in the end. What I try to highlight is that it is a product of worldly relations and many forms of transculturation mainly triggered by colonialism. But when we think about the uses and adaptations the inhabitants made that can be so easily spotted in Casablanca, it becomes incredible. Actually, the modifications are not mere changes or adaptations; some houses have been completely overworked. Then it brings us back to different issues about biopolitics and government matters specific to each society.

One could say people who lived in Écochard’s grid in Casablanca adapted a non-functional house and rebuilt it. Écochard surely thought his system was functional and so people would get used to it. But what actually happened is that they built a new house upon an old structure that did not offer many possibilities because it was too small, as it aimed at creating nuclear family households. Therefore, one could agree on the fact that inhabitants have altered, adapted, and appropriated existing structures to their needs, thus subverting European programs. But when you sort of ignore the original structure, is this still appropriation, is this not production? Nowadays, scholars tend to link appropriation to the concept of freedom. Yet, it can only be done in such a case as the one I am talking about—this is what I am criticizing here: European ground structure is considered the ultimate model from which all other activities have emerged. If you do not follow this Eurocentric idea, you need to accept that the inhabitants have built new structures on top, if that was possible. Until now, this local “growing house” building practice or culture has been associated with the already existing construction methods in the northern African medina. Many studies have ended there so far. But when you read documents that show more concern about the history of the medina as a transcultural encounter site than about French colonial cultural politics aiming at Orientalizing and museumizing the medina as a site of pre-modern forms of production, it gets even more complicated to distinguish whose building practices and cultures we are talking about. And this is what lies at the heart of the problem: that architecture was and is still read as the expression of one cultural identity and not of a different way of living, trading, and articulating that had been exchanging with other cultures long before the beginning of colonial modern projects and in which the northern hemisphere was not always the ruling, colonizing power since other local imperial forces had their own ways of governing people and handled war, trade, and exchanges in their own fashions. These transcultural traces are seldom found in current discourses, as they are mainly based on binaries of the modern and pre-modern, on political identity, and do not focus on transfers, translations, and exchanges.

KA: Philosopher Achille Mbembe has spoken of boundaries referring to the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885. 6 Before that, the nature of boundaries was different. There were areas between ethnic groups that were meant to both separate and bind them. In fact, these were places for traditional trade, war, language exchanges, etc . . . They were exchange areas of a different kind. They would revitalize both cultures . . .

I would like to come back to the complex reappropriation concept and whether any situation or item that embodies it is born from nothing or, on the contrary, is linked to some already existing thing or not.

Let’s take the example of Écochard’s cité verticale and the balconies that have been “re”-covered by all inhabitants.

Indeed, the use of “re” (for reappropriation or repair) as an intellectual western speculation and deduction occurs through the prism of western modern intellectual values and references. From philosopher Immanuel Kant’s critique of philosopher David Hume’s analysis we know that the way we read the world is based on the relationship between cause and effect: “causality”. . . It is true we are unable to think things from within themselves. If you watch a house or a flower, you can be sure that neither of them will be able to think of what it is. . . And so there is no human mind able to think this house or this flower by and within themselves. It always has to think them through the “relation” that exists between this thing and the mind. The relation between themselves consists of both the experience of the object and all the references linked to this relation. This relation is called “correlation” . . .

So when we have a close look at a house and a building that have been “rebuilt” by the inhabitants, then we are just part of this “correlation” . . . Thus, if social architectures that developed through a modern political agenda in North Africa tried to provide the natives with a western vision of modern housing but have been quickly “re”-adapted by them, then it is just an endless process of human knowledge based on “correlation” . . . Indeed, you can do a very simple analogy to link such a behavior by native people to modern western “new” architecture: This is how traditional homes and cities (medina) were built. . . . There is not a single house isolated from another in a medina. Each one is built against another so as to provide both a strong, load-bearing wall to the new house and a connection to another area from the terrace. . . . Even when the first one is in construction, the second one is being built at the same time. . . . In vernacular urbanism, the notion of “city” is the accumulation of houses built “one against another,” which I have been able to observe in North and South Sahara. . . What architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, also known as Le Corbusier, found fascinating in a city like Ghardaïa (Algeria), for instance, is the fact that every street of this medina puts town facilities (market, madrassa, mosque, grocery store . . . ) within walking distance. When he created his first cité radieuse in Marseilles, he claimed it to be a “vertical Ghardaïa,” and each corridor in this modern social housing was called a “street,” as they linked all flats to social facilities you can find in the building, such as a swimming pool, a kindergarten, a school, a church, etc. In fact, he even used to say this is a vertical “Beni Isguen” (Berber name for Ghardaïa). Just as people from North Africa constantly adapted to their natural environment for centuries, they did adapt to their new artificial environment. . . . And to push the “re”-adaptation process further, I would add Le Corbusier’s “reenactment” on a so-called personal creation, which sounds just like a repair of his modern building project, yet with traditional functionalism.

When you pointed out that the first veil story we heard about was a British woman protecting herself from sand, you also meant that, in the Sahara, men are veiled, too. Therefore, indeed, what you see is never what reality is. Especially from a western insight . . .

I recently came upon an interesting story about a vernacular, iconic architecture made of clay in the Sahara. . . . A story I had already heard but that was never established as true. Did you know that Djenné’s mosque in Mali is a fake? Actually, what looks like an authentic twelfth-century mosque is not. . . . This beautiful architecture was “re”-built by the French at the beginning of the twentieth century in 1907.

As far as I am concerned, this is extremely interesting, as we always point out that there is “reappropriation because of dispossession.” But what if the reconstruction of a mosque that has been destroyed several times by local people and foreigners is ordered by a colonial power—in this case, by William Merlaud-Ponty, the French governor?

People in Mali do not complain, but in all former colonies, especially French ones, relationships to colonial architecture are highly problematic. In Morocco, associations such as Casamémoire are doing a great job protecting architectural legacy, but in Algeria, protecting construction built under the former colonial administration is considered nonsense, except for religious buildings. As a matter of fact, most churches were saved due to the fact they became mosques. This is another process of reappropriation, just like so many Ottoman mosques were turned into churches during colonization. . . . It is an endless process, and reappropriation is a loop, too.

MvO: Cultural articulations always have these incredibly rich, multiple trajectories, but traces and transfers are likewise valued differently than the people producing culture: the architect earns cultural and symbolic wealth; the carpenter does not.

On colonial grounds, this perception or creation of value starts with the ideological construction of traditional behaviors and acts against modern behaviors. In this binary pattern, there is competition between two value systems. This pattern is mostly due to European scholars. French Orientalists’ analyses and texts about local economies, crafts, and building traditions either state Moroccan local productions were non-original copies of an Arabian style or call Berber crafting authentic indigenous art as long as it had no disturbing contact with Arabian aesthetics. These Eurocentric and anti-Arabian classifications caused great problems for the post-independence generation, and also do not help to understand what a non-capitalist local economy is even nowadays.

Still, crafts production—the way French powers categorized it—was the local Moroccan economy playing a part in trade relations and style exchanges over centuries. In opposition to what French people believed, not only was it more than a mere stable canon reproducing itself and simply influenced by the Ottoman Empire, but like in the medina district, local production was also an expression and meeting point for different aesthetic trajectories and translocal trade relations with Africa and Europe. Moreover, guilds were in charge of controlling the local market, rewards, trades, and production standards in Morocco over centuries, too.

When the French protectorate took over the government, one of the first interventions concerned guilds; that is to say, local economy and local production. New goods were introduced from other markets. Shoes produced in Asia, for instance, partially destroyed local shoe production. That had an impact on European markets because Moroccan leather products were imported to Europe as well; however, trade relations changed with the introduction of Asian products. Therefore, it also modified the classification of local production, trade relations, and local and traditional crafts, since the intervention into Moroccan guilds by French officials caused these manufactured goods to be seen as traditional and belated. On the one hand, the local economy was now considered traditional/pre-modern, and on the other, the French argued that these forms of “cultural production” would need to be protected and supported by French officials in the future when Morocco would be completely modernized. This double-faced destruction—devaluing and finally protecting local economy—made it possible to declare it a mere extra, a boutique element decorating the real thing that would be consumer goods made from industrialization.

For all of these reasons, the medina district was protected by Lyautey as a kind of living museum about ancient living habits, surrounded by the cité nouvelle built for French colonists. To help Moroccan local trade, Lyautey had an Oriental-modern Habous neighborhood constructed; by the way, it still exists as a central market area isolated from the former European city center. I am talking about this because it is linked to your last comment—the fact we missed this very point in our first project in Berlin at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in 2008, as we did not focus on who actually were the construction workers involved in building the new modern city of Casablanca. We were focusing on governance ideologies and anti-colonial resistance, but not so much on how working relations dramatically changed after French intervention. So how were these workers recruited? Obviously, most of them were Moroccan, while the planners, architects, and technicians were European. I only understood it after reading about it, but the Moroccan workforce was there because of the same intervention in the local economy and because of the catastrophic decrease in handicraft skills that occurred after protectorate intervention in Morocco. So, first you have to destroy local production and value systems, then you have a highly skilled workforce build the new city for Europeans as well as some houses for the Moroccan workforce.

But these free-floating skills were not just used in the name of colonial powers; they also served a lot of other purposes. As you know, the medina house has always been an adapted and growing house. It was always accommodated according to a family’s need, then it could be made bigger when it became too small. This actually was the local building practice, and you can find it in the whole Mediterranean area. Italian villages and smaller cities were built the same way, thanks to adapted construction practices through which buildings can grow. This practice has not been erased by the colonial power; besides many others, this skill survived industrialized means of production and can still be found nowadays. But as a result of colonial rule, local production, being in the margin of industrial chains, has been turned into folklore and transformed into a souvenir culture. But still, this is an economy with its own logic besides other globalized forms of production, and it also makes it possible for people to let houses grow and adapt to the population’s needs.

1 Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004).

2 Ebenezer Howard, Garden Cities of To-morrow, second ed. (Adelaide: ebooks@Adelaide, 2012), p. 11, online at: ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/h/howard/ebenezer/garden_cities_of_to-morrow/index.html.

3 Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator, trans. Gregory Elliot (London: Verso, 2009).

4 Originally published in 1840 in French as “La propriété, c’est le vol!“; Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, What Is Property?: An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government, trans. Benjamin R. Tucker (New York: Humboldt Publishing Company, 1890).orien

5 Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978).

6 See, for instance, Achille Mbembe, “At the Edge of the World: Boundaries, Territoriality, and Sovereignty in Africa,” Public Culture, vol. 12, no. 1 (Winter 2000), pp. 259–284.

Related

De moderne natiestaat hoort etnisch en cultureel homogeen te zijn; na de Tweede Wereldoorlog hebben beide Israel’s toepassing van Zionisme en Arabisch Nationalisme versies van dit purisme opgenomen—met als gevolg dat alles wat zich weigert aan te passen van de sociale gemeenschap wordt weggewerkt en buitengesloten. Na de Zesdaagse Oorlog paste Israëlisch schrijver Jaqueline Kahanoff de notie van Levantinisme toe om het nationaal narratief te betwisten vanuit het perspectief van een minderheid, beïnvloed door haar herinneringen aan koloniaal Cairo. Door zich te verhouden tot Kahanoff’s Levatine schrijfwerk pogen Eva Meyer en Eran Schaerf om het Levantinisme te heronderzoeken; niet als een kant-en-klare oplossing, maar als een complexe en overtuigende —hoewel gecompromitteerde—problematisering van de staat zoals we hem kennen.

As part of FORMER WEST: Documents, Constellations, Prospects, 18–24 March 2013 at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, art critic, poet, and curator Ranjit Hoskote convened a forum on “Insurgent Cosmpolitanism” with cultural theorists and artists whose work addresses and performs the insurgent cosmopolitan condition.

Mariana Botey’s tekst The State Is Coagulated Blood and Bones is geschreven als een proloog op Cooperativa Cráter Invertido's codexstrip Sangre Coagulada y Huesos (Coagulated Blood and Bones, 2021). De twee bijdragen zijn in samenwerking tot stand gekomen en moeten parallel gelezen worden, voor een wederzijdse opbreking van tekst en beeld.

Long weaponized in the service of capital by the agents of neoliberalism, the nation-state is once again upheld as the bulwark of a white ethnos, securing privilege against migrants and immigrants, and against other nation-states in relations of neocolonial dependence. Meanwhile, contemporary art—the globalist heir to modernist internationalism—has become an investment languishing in freeports or stored in the blockchain.

Uit: New World Academy Reader #5: Stateless Democracy, Renée In der Maur and Jonas Staal in dialoog met Dilar Dirik, red. (Utrecht: BAK basis voor actuele kunst, 2015), pp. 27–54

Uit: Once We Were Artists, Maria Hlavajova and Tom Holert, eds. (Utrecht: BAK, basis voor actuele kunst en Amsterdam: Valiz, 2017), pp. 32–52

In 1970–1971, Guyanese radical historian and anti-colonial activist Walter Rodney gave a series of lectures on the historiography of the Russian Revolution at University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Inspired by C. L. R. James’s historical work on the October Revolution, Rodney set out to reveal the parallels between the problems confronting the postcolonial regimes in Ghana and Tanzania, and those that the Bolsheviks faced in building the Soviet state.

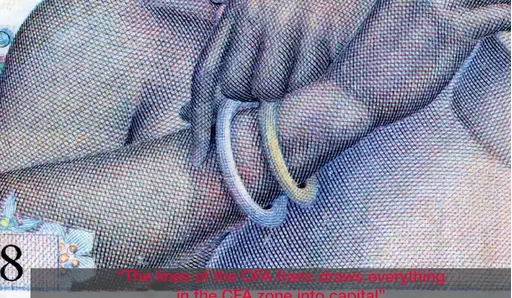

De video The Cut, The Punch, The Press (2021) is onderdeel van Mercurial Relations (2016–doorlopend), een onderzoeksproject van Nina Støttrup Larsen gericht op de munteenheid de CFA-frank.