the Not-Yet Has Long Been Already

Author(s)

Elizabeth A. Povinelli

In haar essay ‘In Some Places the Not-Yet Has Long Been Already’ (voor het eerst gepubliceerd in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, uitgegeven door BAK, basis voor actuele kunst en MIT Press, 2021) put Elizabeth A. Povinelli uit haar werk als onderdeel van het Karrabing Film Collective. In de tekst contrasteert ze de temporele oriëntatie van het laat-koloniale liberalisme – getroebleerd door de op handen zijnde catastrofes van een totale klimaatinstorting – met de voorouderlijke catastrofes van kolonialiteit en slavernij, die zowel van het verleden als het heden zijn. Deze voorouderlijke catastrofes, aldus Povinelli, ‘blijven groeien uit de grond die kolonialisme en racisme hebben bewerkt, in plaats van op te duiken aan de horizon van liberale vooruitgang.’

Three members of Karrabing Film Collective—Rex Edmunds, Cecilia Lewis, and I—were travelling to Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia from Belyuen in order to attend a meeting with the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority (AAPA). The term “karrabing” in our name refers to neither a place nor a people. In the Emmiyangel language, karrabing refers to the state when the vast coastal tides are at their lowest, and is contrasted by karrakal, when the tides are at their highest. But as more than a linguistic sign or reference, karrabing refers to how people should and do belong to each other and the more-than-human worlds that constitute their lands and lie within them. In other words, karrabing is a concept. Karrabing means, as Rex, Cecilia, and other members of the collective have stated, that while members inside the group may have different languages, lands, stories, and totems, these “separate-separate” aspects all formed from the recurrent actions of tides, ancestral totemic movements, their own kin and marriage ties, and the constant ordinary interactions with each other and the more-than-human worlds that connect country and people. Against a settler colonial proprietary imagination, Karrabing Film Collective (hereafter referred to as Karrabing) insists they have their roan-roan (one’s own, in the local creole) places, but these different places and their stories are irreducibly connected to other places. 1

It was mid-December 2020 when we began our trip, and we were watching a storm gather over the harbor. The rain had begun in earnest, which was a good sign after two years in which the monsoons had never properly arrived. Creeks that had never run dry in our lifetimes had been bone dry for a year. As we drove along the bottom side of the city where the harbor was, Rex looked at what was left of the mangroves in the wake of intensive housing and industrial construction and said, “Don’t eat tjimerre (long balm, sea snails) from these mangroves.” Of course, we knew that people did, and so it wasn’t surprising that our conversation turned to the topic of a small Indigenous city camp nearby whose inhabitants sometimes collected food from these sea swamps. Again Rex, who once lived in the camp, speaking this time with our local gallows humor said, “That place is already poisoned from petrol dumping, and now the highway surrounding it, more pollution. Might as well eat poison tjimerre with your petrol tea and pollution breath.” Just as we rounded into the city center, the storm hit.

The environmental geography that surrounded us as we drove from Belyuen to Darwin maps onto two different ways of conceptualizing the social tense of toxic late liberalism, climate collapse, and aesthetic practice. When it comes to toxic late liberalism and climate collapse, two spectral orientations battle for our attention. On one hand, western pundits push us to look at the catastrophes approaching over the horizon, or at this point, already hitting the shoreline. What was on the horizon has now landed—the planet’s over-heating, as a result of the climate toxicity of not merely carbon capitalism but capitalist expansion and domination of the entire terrain of the earth, is in full gear. What a shock it must be for those of whom the horizon has for so long been brightly lit with possibilities. What if the horizon holds not just one, but a series of ever more colossal storms? First is climate collapse, then Covid-19, then a massive environmental shift. How do they right themselves when they have long been told that the horizon is where the truth, goodness, and justice of liberalism reside?

This hopeful orientation toward the horizon is countered by another threat: the catastrophe as ancestral, as something that once arrived on the horizon and has bubbled out of the ground ever since. The arrival over the horizon of explorer and settler boats didn’t herald the establishment of a new Jerusalem or a revolution which would have served as the exemplary model of political action. 2 Nor did those West Africans, enslaved in the belly of cargo hulls, view themselves as being delivered to a divinely benighted land. The arrival of these boats presaged calamitous storm. This storm took roots in the land, extracting and processing what it deemed valuable—ecologies, labor, and cultural goods—and left behind ever more concentrated toxic tailings. When viewing toxic late liberalism and climate collapse from the perspective of ancestral catastrophe, the nature and meaning of material existence is not merely inverted. The ancestral catastrophe is not the same kind of thing-event as the coming catastrophe, nor does it operate within the same temporality. When we begin with the catastrophe of colonialism and enslavement, the location of contemporary climatic, environmental, and social collapse rotates and mutates into something else entirely. Ancestral catastrophes are past and present; they keep arriving out of the ground that colonialism and racism tilled rather than emerging over the horizon of liberal progress. Ancestral catastrophes ground environmental damage in the colonial sphere rather than in the biosphere; in the not-conquered earth rather than the whole earth; in errancies rather than ends; in waywardness rather than war; in maneuvers, endurance, and stubbornness rather than domination, resistance, despair, and hope.

This is why I and others have said that if you want to know what is not yet, look to where it has long already been. And as you look, remember that unless you contribute real effort toward changing these ancestral dynamics, the new round of ruinous action will not simply level the playing field, nor merely place those who have long benefitted from toxic liberal capitalism and its newer illiberal versions—it will lash more forcefully those who have already borne the toxic and climatic burden of racial and colonial capitalism, something the Covid-19 pandemic has made starkly clear.

II.

The three of us driving to AAPA were joined by three other Karrabing members, Angelina Lewis, Kieran Sing, and Sandra Yarrowin. We were showing our most recent film, Day in the Life (2020), to some of the staff responsible for recording and processing the registration of indigenous sacred sites. Day in the Life depicts kinds of obstacles encountered across five points of a typical day at Belyuen, featuring a multilayered hip-hop soundscape punctuated with samples from the left and right wing white media. More than a film screening itself, the meeting was a continuation of discussions about potential policy changes within the agency regarding Karrabing’s understandings of the irreducible dual nature of their connections to the land. The law stated that persons belonged to specific places (mebela roan-roan land, in the local creole), but these specific places, and thus the character of belonging itself, depends on numerous modes of connectivity to other places—environmental connections such as the seas, freshwater swamps, winds, animals, and plants; marriage connections; ritual connections; and the ancestral formation of the geography of the self as various ancestral beings came into contact with each other and then went their separate ways. For Karrabing, this irreducible dynamic of “roan-roan and connected” is not in the past. All these more-than-human agencies, like they themselves, must make their way in the current conditions of toxic late settler liberalism. They must maneuver, endure, and stubbornly hold on in the ancestral present.

We see a similar split-screen orientation in aesthetic theory of indigenous artistic practices as we do in the present bonding of the climate with toxicity. There is a meaningful distinction between traditional and modern indigenous arts and objects. Animating this distinction is the critical theoretical distinction between the cult image and the art image. I am, of course, referring to Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno who, for all their discussion about the possibilities of the art image as a break or derivation from its original ritual function, ground the emergence of modern art in a break from what both call the cult image. Let me say, for brevity’s sake, that for these two men the cult image mistakes the location of human agency—placing it in a realm of fetishization as opposed to that of human social relations. Benjamin was wrong to see politics emerging as the goal of art after its separation from that of the cultic image. The very separation of art and cult was political in its origins; it was part and parcel of the colonial catastrophe.

The politics of western appropriation of Native American and indigenous art hewed to this division; Adorno and Benjamin, for example, were themselves articulating the social tense of colonial and racial understandings of “primitive art” rather than inventing revolutionary categories. The history of the west’s encounters with the expressive practices of colonized people can be put into this gross timeline: stolen curios; ethnographic objects; material for the inspiration of modern western art, first stolen without attribution, and then placed side-by-side in various large museum shows before being separated into ritual objects to be repatriated, or not, as better or worse aesthetically realized objects.

The ancestral catastrophe is not merely the inverted image of the catastrophe on the horizon, as such Karrabing’s view is that the cult image is not the elevation of the cult image over the art image. Instead, it is a refusal and displacement of the western division and an opposition of cultic and modern aesthetics as such. This refusal of the western division of cult image and art image is not a refusal of their abiding relations with the more-than-human world, or of the specific expressive semiotics of communicating with that world. Instead, it is a practice of knowledge. Thus, in the film Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland (2018) and the rest of our films, some aspects of ancestral narratives are left out and other aspects shown and heard but not explained. As Aiden walks through his roan-roan and connected world with his uncle and brother, viewers splinter into those who understand the meaning and connections between visual and sound elements, those who understand the potential of such connections although not the actual ones in the film, and those who don’t look for such interpretive clues. Thus Karrabing’s aesthetic practice builds on their ancestral ways of showing without telling, mapping “open” ways of telling an ancestral truth onto “inside” ways of understanding it. Think here of what Gregory Bateson, Gilles Deleuze, and Félix Guattari would later understand as the relationship between maps and territories.

The practice of Karrabing’s art is thus turned away from the audience that does not understand—even if it is addressing and absorbing them into their work—and turned toward themselves and the others who do understand. They can make their work visible to each other and their coming generations without giving it away. This making work available is not merely aesthetic nor merely addressed to humans. This is because Karrabing’s aesthetic practices are not based on a theory of beauty, desire, or even politics, but on an understanding of the fundamental dynamic between existential jealousy and reparative, although always insufficient, attentiveness—the key thematic of Wutharr, Saltwater Dreams (2006) and The Jealous One (2007)—and the concentration and orientation of the senses. For Karrabing, jealousy and attentiveness crisscross the human and more-than-human world, and is exemplified in the hunting question, “What will this thing bite?” To answer this question, a person has to have a deep understanding of the kind of thing one is luring and its typical and unusual habitats and modes of existence. It doesn’t matter what is being bitten; there is a deep disinterest in what will elicit a bite, but an extraordinary interest in, and attentiveness to, the tendencies and thus manipulability of the thing you wish to bite. This does not apply merely to nonhuman animals but to human and ancestral beings. But these two categories also bite back if one is not paying attention to them. This was seen in the refrains of the ancestors in Wutharr, Saltwater Dreams, “Punish them, punish them,” who were enraged that the human protagonists had not visited them for some time. In Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland, the end of the journey is a meta-jealousy event. Europeans had mistreated the world, failed to attend to its needs, and doubled down on this neglect so much that the Indigenous protagonists had to decide whether they should release a totemic plague that would bite everyone indiscriminately.

In this sense, Karrabing’s films and installations are geared toward concentrating and orienting the senses to attend to the memory and practice of the ancestral present and the ancestral catastrophe they and their more-than-human world find them-selves facing. They are an askesis for the ancestors. They are acts of artistic expression for their totemic lands without being western instances of cultic or art works. They herald what is to come because it is already here.

1 Karrabing Film Collective discuss this conceptual meaning attogetherinart.org

2 I refer here to Hannah Arendt’s justification of the sadistic colonization of the Americas, in which she states that “[c]olonization took place in America and Australia, the two continents that, without culture and a history of their own, had fallen into the hands of Europeans.” Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1973), p. 186. For trenchant critiques of Arendt’s position see Kathryn T. Gines, Hannah Arendt and the Negro Question (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014); and Fred Moten, The Universal Machine (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018).

“In Some Places the Not-Yet Has Long Been Already” appears in Jeanne van Heeswijk, Maria Hlavajova, and Rachael Rakes, eds., Toward the Not-Yet: Art as Public Practice (Utrecht and Cambridge, MA: BAK, basis voor actuele kunst and MIT Press, 2021), republished here with permission of the author. Toward the Not-Yet: Art as Public Practice, is a reader in BAK’s SUPERBASICS series and can be purchased at BAK or via MIT Press.

Related

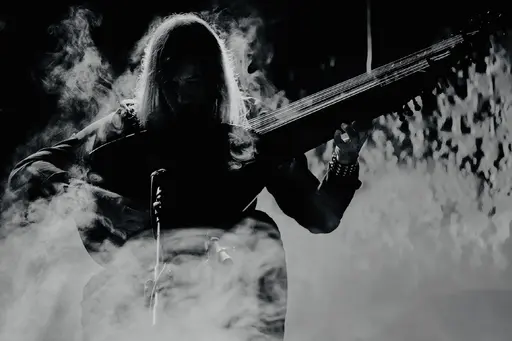

In dit korte afro-futuristische verhaal, geschreven door Amiri Baraka in 1995, ontdekt een ongenaamde uitvinder een manier om terug te reizen door de tijd – door muziek. “I duwde de Anyscape in de Rhythm Spectroscopic Transformation. En toen stemde ik het af zodat Anywhereness kan worden gecombineerd met de Reappearance als muziek!” legt de uitvinder uit. “Nu voeg ik Rhythm Travel toe! Je kunt verdwijnen en verschijnen waar en wanneer die muziek speelde.”

Tijdsgebonden drag, erohistoriografia, chronomornativiteit, geilheid onder het kapitalisme, ritme, dansen en 'crip time'. Dit zijn een paar van de onderwerpen die worden genoemd in het interview met Elizabeth Freeman, queer theoreticus en auteur van de boeken Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (2010) en Beside You In Time: Sense Methods & Queer Sociabilities in the American 19th Century (2017), en Amelia Groom, co-editor van de 'No Linear Fucking Time' focus op Prospections.

Reclamations of time, geared toward community and temporally “local” orientations, animate this interview with artists and activists Black Quantum Futurism (Rasheedah Phillips and Camae Ayewa), who draw from Afrofuturism, quantum physics, and “Afrodiasporic traditions of space and time that are not locked into a calendar’s date or a clock’s time." As discussed in the interview (which first appeared in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, published by BAK and MIT Press, 2021), BQF’s recent and forthcoming projects directly challenge imperial and colonial standardizations of time.

Dit essay, oorspronkelijk gepubliceerd in het Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies, is een onderdeel van muzikant en schrijver JJJJJerme Ellis’s veelzijdige project The Clearing. Ellis beschrijft het bos en zijn open plekken als “plekken van weerstandige ‘black oralities’” en verkent hoe stotteren, Blackness en muziek kunnen figureren binnen de praktijken van het weigeren van hegemonisch tijdsbeheer, spraak en ontmoeting.

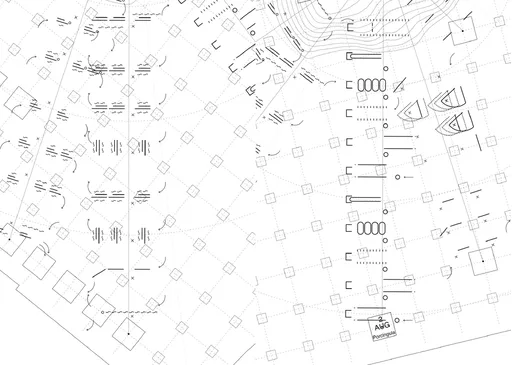

Wanneer inheemse gemeenschappen worden gevraagd om bewijs te tonen van hun traditionele connectie met hun voorouderlijke landen, respecteert wat Westerse legale instanties accepteren als documentatie niet volledig hoe stammencultuur en traditionele manieren van kennisoverdracht werken. Het onderzoeksproject en boek The Language of Secret Proof (2019), geschreven door Nina Valeria Kolowratnik, reageert op de ervaring met de productie van bewijsmateriaal van bewoners in Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico. Dit boek bevecht de omstandigheden waaronder de rechten van inheemse volken om traditioneel land te beschermen en terug te winnen worden behandeld in het wettelijk kader van de Verenigde Staten.

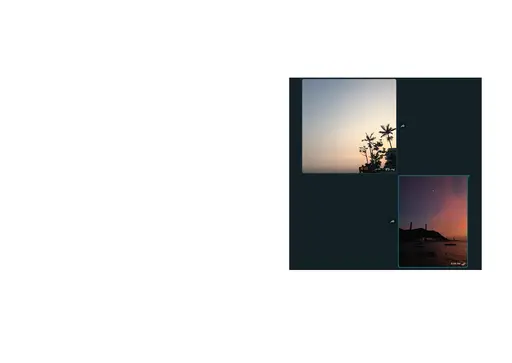

SEA – SHIPPING – SUN (2021) is een korte film en meditatie over maritieme handelsroutes, geregisseerd door Tiffany Sia en Yuri Pattison. De film werd opgenomen over de span van twee jaar, maar is geedit om het eruit te laten zien alsof het één dag is, van zonsopgang tot zonsondergang. De film speelt de soundtrack van scheepsberichten uit het archief van BBC Radio 4 uitzendingen. SEA – SHIPPING – SUN werd gemaakt met de intentie om de kijker slaperig of relaxed te laten voelen, en verzamelt een visie van verstrengeling. Wij worden achtergelaten met de overblijfselen van geschiedenis: een zachte, wiegende waltz over de zee.

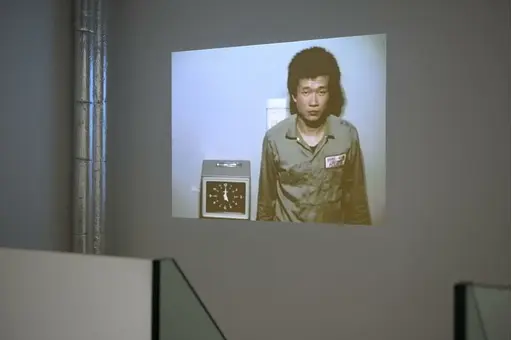

In dit essay reageert Amelia Groom op Tehching Hsieh's werk Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981) (1980-1981), een van de stukken die te zien is als onderdeel van de tentoonstelling No Linear Fucking Time bij BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Door een lezing van het gelijktijdige anti-werk lied 9 to 5 (1980) van Dolly Parton reflecteert Groom op de historische verschuivingen in de manieren waarop werknemers werden en nog steeds worden uitgebuit door technieken van tijdsdiscipline.

Grappling with the imposed linearity of timespace as a fundamental feature of colonial violence, this essay by Promona Sengupta (also known as Captian Pro of the interspecies intergalactic FLINTAQ+ crew of the Spaceship Beben) proposes a mode of time travel that is “untethered from colonial imaginations of the traversability of time and space.” While coloniality has enforced an externalization of time and space as things outside the body, Sengupta affirms practices of relational care and survival that restore time and space as embodied realities.

Weird Times (2021) is een chapbook van 30 pagina's door kunstenaars Tiffany Sia en Yuri Pattison over de tijd aflezen en hegemonie. Het bevat Sia's schrijfwerk en beelden geselecteerd door Pattison, en geeft een korte geschiedenis weer van de ontiwkkeling van technologieën voor tijdregistratie. De klok wordt gedemonteerd als een politiek werktuig, een metronoom van dwang en een versneller van oorlogsmacht. Uit deze mechanieken verschijnen weerstandige ‘counter-tempos'.

Een online gesprek met performance kunstenaar Tehching Hsieh, schrijver Amelia Groom en schrijver en curator Adrian Heathfield, geleid door Rachael Rakes, BAK curator Public Practice, op 20 januari 2022. Het gesprek neemt Hsieh's werk als uitgangspunt voor het bespreken van onder andere perfomatieve tijd, werktijd, gaten en ritmes van uithoudingsvermogen.

The No Linear Fucking Time Bibliografie is een zich ontwikkelend naslagwerk waarin wetenschappelijke en artistieke teksten worden gebundeld die betrekking hebben op de verscheidene onderzoekslijnen binnen dit project.

In ‘Reclaiming Time: On Blackness and Landscape’ (voor het eerst gepubliceerd in PN Review issue 257 in 2021), bekijkt dichter en schrijver Jason Allen-Paisant de geracialiseerde maatschappelijke contexten en moderne milieuconstructen die ‘Zwarte levens disproportioneel beroven van de voordelen van tijd.’ Hij put uit zijn poëziebundel Thinking with Trees om een koloniale epistemologie van de natuur te schetsen, en de rol van poëzie te benadrukken in het genereren van vormen van Zwart verwantschap en politiek bewustzijn, gebaseerd op een hernieuwd gevoel van ‘diepe tijd’. De vraag of het mogelijk is om middels poëzie ‘tijd terug te claimen’ staat centraal in de tekst.

Als hij door de ‘Nothing To Declare’ uitgang van het vliegveld London Stansted loopt, ziet Sam Keogh drie grensbewakers: een varken, een eenhoorn en een bezorgde cartoonklok. Pig Eater is het script voor een monoloog dat voor het eerst opgevoerd werd als onderdeel van Keogh’s tentoonstelling Sated Soldier, Sated Peasant, Sated Scribe, in Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, Londen in 2021. Het verweeft fantasieën over overvloed en de afschaffing van werk; over feesten en rusten; over sabotage, anachronisme en het ‘opfokken’ van lineaire tijd.

In dit gesprek met Walidah Imarisha (voor het eerst gepubliceerd in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, BAK en MIT Press, 2021), schetst de schrijver en activist haar concept van ‘visionaire fictie’ als een verbeeldingspraktijk om toekomsten te verlossen van het bolwerk van lineaire tijd. Imarisha put uit haar werk als strafrechtelijk abolitionist, en spreekt specifiek tot de bewegingen en ideeën die voortkomen uit de Zwarte strijd in de Verenigde Staten. Ze benadrukt dat we ons bij het veranderen van de toekomst moeten verhouden tot het verleden: ‘specifiek vanuit een kader gericht op gedekoloniseerde, niet-lineaire dromen van vrijheid die gegrond zijn in de strijd van gemeenschappen van kleur voor autonomie en bevrijding van kolonialisme.’

In haar essay ‘In Some Places the Not-Yet Has Long Been Already’ (voor het eerst gepubliceerd in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, uitgegeven door BAK, basis voor actuele kunst en MIT Press, 2021) put Elizabeth A. Povinelli uit haar werk als onderdeel van het Karrabing Film Collective. In de tekst contrasteert ze de temporele oriëntatie van het laat-koloniale liberalisme – getroebleerd door de op handen zijnde catastrofes van een totale klimaatinstorting – met de voorouderlijke catastrofes van kolonialiteit en slavernij, die zowel van het verleden als het heden zijn. Deze voorouderlijke catastrofes, aldus Povinelli, ‘blijven groeien uit de grond die kolonialisme en racisme hebben bewerkt, in plaats van op te duiken aan de horizon van liberale vooruitgang.’

‘Dysfluent Waters’ is onderdeel van het multidimensionale project The Clearing van muzikant en schrijver JJJJJerome Ellis, respectievelijk een boek uitgegeven door Wendy’s Subway en een gelijknamig album uitgebracht door NNA Tapes in 2021. Hij ziet het bos en haar open plekken als ‘plaatsen waar al eeuwenlang verzet plaatsvindt middels zwarte gesproken cultuur.’ Ellis onderzoekt hoe stotteren, zwartheid, en muziek een rol kunnen spelen bij verzetspraktijken tegen dominante voorschriften voor de beleving van tijd, spraak en ontmoeting.

In haar tekst ‘Dearest Zen (Letters to Lichen)’ presenteert kunstenaar en wetenschapper Adriana Knouf toekomstige liefdesbrieven aan korstmossen: de samengestelde symbioten van schimmels en algen of cyanobacterieën. Bezien door de lenzen van de ‘xenologie’ (Knouf’s term voor de studie, analyse en ontwikkeling van het vreemde, buitenaardse en andere) en trans*-tijdelijkheden, onderzoekt ze manieren om te leren van, en opgetogen mee te doen met, intimiteiten en uitwisselingen tussen verschillende organismen.

In ‘Immortals: on the Ancient Future Lives of Stone and Plastic’ verweeft Marianne Shaneen verhalen, geschiedenissen en ontologieën van twee materialen: steen en plastic. Als quasi-onsterfelijke substanties zijn steen en plastic getuige van de catastrofale effecten van uitbuitende lineariteit, terwijl hun levensloop veel langer is dan dat van een mensenleven. Dit essay verweeft deze twee materialen, die schommelen tussen het geologische en synthetische, en die diep ingebed zijn in industrieel-kapitalistische ontwikkeling.

‘The Clearing: Melismatic Palimpsest’ is onderdeel van het multidimensionale project The Clearing van muzikant en schrijver JJJJJerome Ellis, respectievelijk een boek uitgegeven door Wendy’s Subway en een gelijknamig album uitgebracht door NNA Tapes in 2021. Hij ziet het bos en haar open plekken als ‘plaatsen waar al eeuwenlang verzet plaatsvindt middels zwarte gesproken cultuur.’ Ellis onderzoekt hoe stotteren, zwartheid, en muziek een rol kunnen spelen bij verzetspraktijken tegen dominante voorschriften voor de beleving van tijd, spraak en ontmoeting.