Author(s)

MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), Yvonne Phyllis, Brenna Bhandar, Aya Bseiso, Layal Ftouni. Jennifer Irving, Tareq Khalaf, Gleare Khoshgozara, Marie Nour Hechaime, Philip Rizk, Bobby Sayers, Shela Sheikh, and Kasia Wlaszczyk

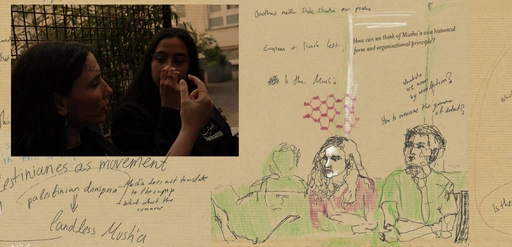

Convened by Johannesburg-based Yvonne Phyllis and MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), the working session Failing, Dreaming, Doing: rehearsing abolition sought to conjure alternate imaginaries of life and labor with earth, beyond the regimes of colonial and racial enclosure. The following text was collectively written by the working session’s participants: Brenna Bhandar, Aya Bseiso, Layal Ftouni, Jennifer Irving, Tareq Khalaf, Gelare Khoshgozara, MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), Marie Nour Hechaime, Yvonne Phyllis, Philip Rizk, Bobby Sayers, Shela Sheikh, and Kasia Wlaszczyk and was read out by Nare Mokgotho as part of “PROPOSITION 3 Failing, Dreaming, Doing: rehearsing abolition” during the Usufructuaries of earth convention public program, Saturday 25 May 2024 at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht.

________________________________________________________________________________

a group, of many walks, many lives,

to share failures, dreams, and actions;

to compare notes; to contribute strategies; to collectively hold grief.

We sought to explore what it means to reimagine land outside of the notion of it as property—and to seriously think through models and examples of work from our own experiences, from organizing, from our contexts, and from our own practices, to redefine our relationships to the land.

We shared that . . .

. . . in the spaces of strategies for land justice: failing, dreaming, and doing are not mutually exclusive. It is from failure that we dream and do.

. . . any contemporary spirit of militancy and abolition necessitates an acknowledgment of impossibility. It may sound paradoxical to advocate for “doing” while acknowledging impossibility, but failure is a part of doing and dreaming: there is no separation.

The greatest failure in fact, is alienation from the land. A once existing relation has been violently ruptured through colonialism, apartheid, and genocide—and from which further violence follows, in power and in labor. Across the earth.

Because of this, that alienation becomes a kind of death—for the failure of alienation continues. It is a perpetual cycle.

Our response must be a continuous rehearsal: a perpetual cycle of resistance, a commitment to always respond to failure with dreaming and with doing. We must continuously seek out, ask how to make life in proximity to death.

How do we repair ourselves, even without the prospect of the law enabling justice, and, particularly, despite the law?

Notions of resistance and refusal are the articulation of failing while dreaming of otherwise possibilities beyond ruination: giving a horizon to a possibility of non-property and of return.

We shared that . . .

. . . abolition must include liberating ourselves from the language of the state and of property: not seeking language alternatives, but rather liberating ourselves from the current grammar of colonialism, capitalism, and the state. For a commitment to land justice—to redefine and to imagine and dream otherwise—we must use different languages. For the language we have been given and that is imposed upon us is a language that structures alienation and violence.

We must ask ourselves, when does “earth” become “land,” and when does “land” become “property”? Similarly, in the contexts of the commodification of land, when do “human beings” become “labor”?

What are the languages that enable our land struggles? What lifeworlds are enabled through a liberated approach to how we make meaning?

The word “place” in the Arabic language is related to a constellation of other meanings and derivatives that mean “to remain,” “species,” “capabilities,” “mastery,” “to be,” and “universe.” Even beyond words, what other forms of language are available to us, in action, or in the body? Can we map the land based on how it carries the body of human sound cast within the landscape, affiliating ourselves and our kin by our association with particular animals and landscapes in names and totems—an intimacy with the land? Naming the more-than-human based on our relationships with them, can “land” be understood in an expansive sense? “As a web of relations and an act of making place,” rather than as an object with which to have a relation of ownership, domination, and exploitation?

We shared that . . .

. . . a re-imagination of language also enables a reclaiming of belonging to and with the land.

. . . the concept of “right” in Arabic is Haq, which is “right” in legal terms, but also “justice” and “truth.” And yet justice and truth are not strictly answerable through the law, but rather through struggle for truth and justice as a way of life.

. . . the struggle to a “right to life” and a “right to land,” both of which are central to Palestinian liberation, exceed the limits of the law.

Land law, as discussed through many examples in our conversation, legislates precarity. It is in conflict with life. We must redefine our relationships of land outside of notions of the law and therefore, inherently, outside of property. We thought together beyond the land as property, a thing, a noun, and rather about “landedness” as verb. “Landedness,” as opposed to being landless, implies having land and being rooted (having “landed”) somewhere. We spoke of land-workers reclaiming a sense of belonging to the land through “place-making,” disrupting labor relations with land owners. We spoke of others using language and orality, dance, song, embodied ritual as a way of bringing into being ways of relating to land, waters, and non-human lifeworlds that displace private property.

We discussed landedness as “being or becoming with” the land, not feeling you are outside of it. Engaging the land in a manner that does not privilege the eye and vision—avoiding an ocular-centric relation—landedness is instead an aural and embodied relation to the land. Again, this embodiedness goes beyond existing paradigms of colonial and commodifying language.

We shared that . . .

. . . land justice is always in solidarity with other places, thinking with other places and lifeworlds in the way we dream and do. For land alienation, the stories of how we have arrived here, and how it works in different places in the world is somehow very similar. And we might learn from each other’s failures or from each other’s dreams and ways of doing; there are many different ways of doing, of enacting abolitionist ideas. When we understand each other’s stories, we also understand an important reality: return is not the reversal of leaving or expulsion, but we have to understand that the returnee has also been changed by the processes of capitalism and alienation from the land. We must also understand the extent of our loss and alienation from the land. To understand our relationship with land as belonging and as being is to also understand the severity of the loss that many of us have experienced and the effort that will be required to reconnect with the land and to begin to undo the alienation. What is to be done with the changes in us?

We shared that . . .

. . . a fundamental site of resistance is in everyday practice: just doing is resistance.

For many, land justice is about insisting on being there, belonging and being present. This insistence is resistance. We learned of Aunt Azziza, the matriarch of a family, who faces an ongoing threat and violence to her land and culture in Palestine—and who shares and teaches, handing over knowledges to younger family members through oral traditions. Creating a space for both material and spiritual nourishment, producing our own food, eating together, walking together, thinking together, laughing together as everyday practices on the land: Aunt Azziza reminds us that resistance is present in creating spaces where freedom is lived and not imagined.

We learned of the practice of burying umbilical cords as a symbol of belonging to the land, and as an assertion of returning to that land to join one’s ancestors through burial.

We shared that . . .

. . . land—earth—acts as a protagonist, carrying the past and future lives of the disappeared. Earth is a carrier for the ghosts dwelling in the landscape, a carrier of the exiled, and the rehearsal of return.

But importantly, us who live here don’t regard the death of our people as the end of life . . .

Thina sizwe esimnyama

Sikhalela izwe lethu

Elathathwa ngabamhlophe

Sithi mabawuyek’umhlaba wethu

Related

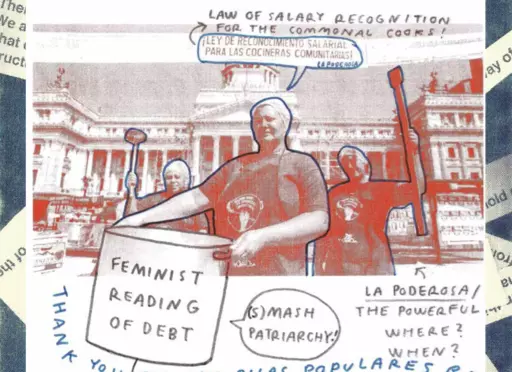

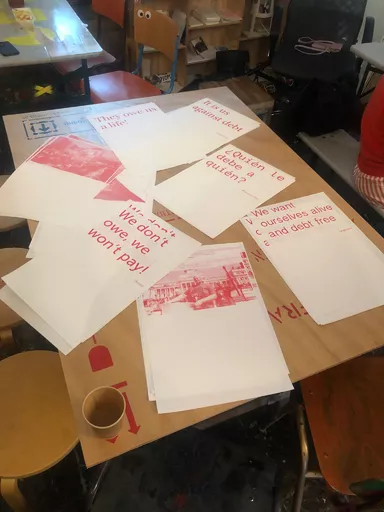

Held in the context of Usufructuaries of earth: chapter two, reading groups and publication, a reading group was convened by Iliada Charalambous and Philippa Driest on 28 April 2024 titled Undoing Debt, at KIOSK, Rotterdam. The reading group looked at debt as a form of gendered and financial violence and sought how to, in turn, “undo debt” through learning shared political tools and vocabulary inspired by transnational feminist movements.

Convened by Johannesburg-based Yvonne Phyllis and MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), the working session Failing, Dreaming, Doing: rehearsing abolition sought to conjure alternate imaginaries of life and labor with earth, beyond the regimes of colonial and racial enclosure. The following text was collectively written by the working session’s participants: Brenna Bhandar, Aya Bseiso, Layal Ftouni, Jennifer Irving, Tareq Khalaf, Gelare Khoshgozara, MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), Marie Nour Hechaime, Yvonne Phyllis, Philip Rizk, Bobby Sayers, Shela Sheikh, and Kasia Wlaszczyk and was read out by Nare Mokgotho as part of “PROPOSITION 3 Failing, Dreaming, Doing: rehearsing abolition” during the Usufructuaries of earth convention public program, Saturday 25 May 2024 at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht.

________________________________________________________________________________

Held in the context of Usufructuaries of earth: Chapter two, reading groups and publication, a reading group spanning two days was convened by Joud Al-Tamimi and Lama El Khatib on 4 and 5 May 2024 titled And in your throats, a sliver of glass, a cactus thorn and On Value-Disrupting Activity, at bookstore خان الجنوب khan Aljanub, Berlin and Hopscotch Reading Room, Berlin respectively. Mokia Laisin put together a collaborative collage of annotations made during both days of the reading group discussions with input from Miriam Gatt on 4 May 2024.

Held as part of day two of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 25 May 2024, this video documents a closing conversation between Yvonne Phyllis, Denise Ferreira da Silva (online), Verónica Gago, Stefano Harney, Lena Wilderbach, and Brenna Bhandar (online), moderated by Shela Sheikh.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents the words of welcome by Maria Hlavajova, followed by a conversation between Marwa Arsanios and Wietske Maas—as means of introduction to the Usufructuaries of earth public program.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents a conversation between Brenna Bhandar, Yvonne Phyllis, and Ruth Wilson Gilmore(online), moderated by Layal Ftouni.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents a conversation between conversation between Philip Rizk and Marwa Arsanios following a screening of Rizk’s film Mapping Lessons (2020).

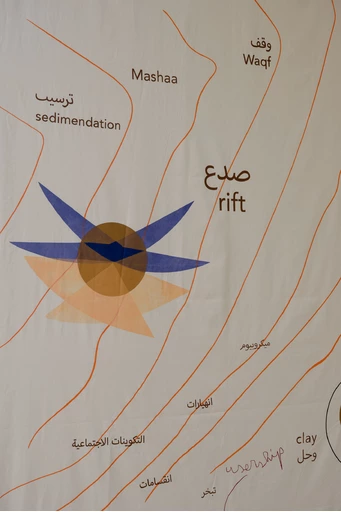

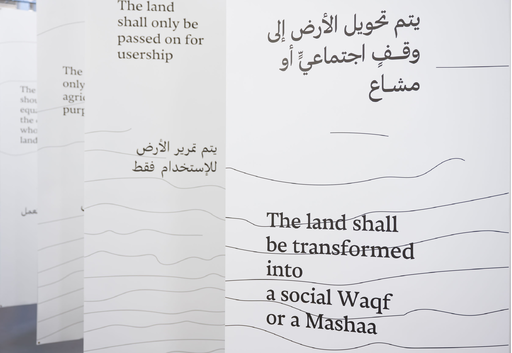

This essay, “Enclosures from Below: The Mushaa’ in Contemporary Palestine,” from geographer and researcher Noura Alkhalili is shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Amman reading group convened by artist-led research group Bahaleen involving locally-invited artists and researchers.

This chapter, “Scholar-Activists in the Mix,” from Ruth Wilson Gilmore's Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation (2022) is shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Amman reading group convened by artist-led research group Bahaleen involving locally-invited artists and researchers.

This chapter, “Improvement,” from legal scholar Brenna Bhandar’s Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (2018) is one of the readings for the Amman reading group.

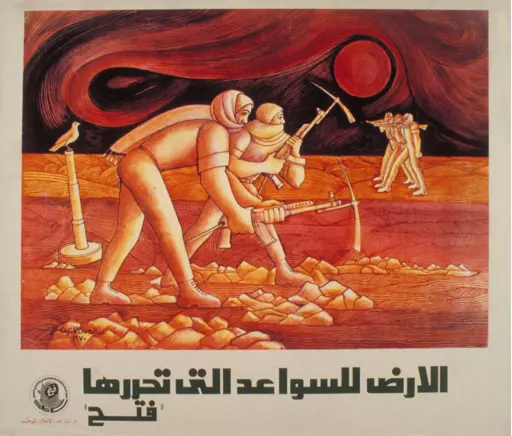

In the context of Usufructuaries of earth: Chapter two, reading groups and publication, a multi-day roaming reading residency, convened by the artist-led research group Bahaleen is held from May 9–13 2024, along the hilltops of Jerash and the edges of Palestine—an hour’s drive from Amman. Invited artists and researchers join Bahaleen in traveling by car and on foot, navigating notions of access and return. Together they grapple with the possibilities of disruption and dissent, aiming to articulate a liberatory vision of the commons from within this geopolitical conjuncture. During the reading residency a board of images and sources were assembled as a harvesting. The images are shared below as screengrabs from this image board, with accompanying links where appropriate.

Originally published in Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Blackness (Duke University Press, 2020), this essay, "Reading the Dead: A Black Feminist Poethical Reading of Global Capital" by academic, philosopher, and artist Denise Ferreira da Silva is shared here in the context of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. This chapter is one of the readings for the Berlin reading group convened by Joud Al-Tamimi and Lama El-Khatib, titled “On Value-Disrupting Activity,” at Hopscotch reading room, 5 May 2024. This reading group explores the political and theoretical stakes of value as it links to violences enacted on and through land and property in Palestine and elsewhere.

“What is a revolution that neither overthrows a state order nor institutes a lasting one of its own?” This is the question that teacher, author, and political theorist Nasser Abourahme poses in “Revolution after Revolution: The Commune as Line of Flight in Palestinian Anticolonialism.”

Three excerpts are republished here from researchers and activists Verónica Gago and Lucí Cavallero’s A Feminist Reading of Debt (London: Pluto Press, 2021). The text opens with a simple concept: that contemporary debt cannot be understood by only looking at “public debt,” and must instead look at the indebtedness present in everyday life. The authors call for debt to be adopted by social movements as a key issue, and furthermore, for people to be cognizant of the links between debt and sexist violence.

This is an extract from the chapter “Debt and Study,” in Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (2013). Across its three sections—Debt and Credit, Debt and Forgetting, and Debt and Refuge—this extract traces the sites and practices of “desired” and undesired debt that perforate contemporary financial capitalism and western culture. The text moves through different people who are marked as debt carriers, such as the precariat, the student, and racialized people, among others.

“Riot Now: Square, Street, Commune” is a chapter from political theorist Joshua Clover’s Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings (Verso, 2016). Taking the classical Greek agora—a place of assembly and commerce—as a starting point, Clover suggests that it is perhaps no coincidence that many of the riots and occupations that emerged in recent decades either happened or began in modern squares. He speaks of how this emergence of rioters corresponded to “an underlying political-economic unity, a material reorganization of society, which provide[d] them a shared set of problems and a shared arena in which to confront them.”

Charting the interconnectedness of capitalism, colonialism, and nationalism, Peter Linebaugh’s “Palestine & the Commons: Or, Marx & the Musha’a” speaks of “the violence of mapping, titling, buying, and selling which cast people into cities and camps following their expropriation from the land.”

Originally published in Kohl Journal, this interview is between Samanta Arango Orozco, a member of Grupo Semillas, and the artist Marwa Arsanios, who is co-convening with BAK the multi-chaptered project Usufructuaries of earth until 2 June, 2024.

A slow-growing table of contents for the Usufructuaries of earth online reader. The reader emerges, to begin with, as a constellation of archival texts assembled here through the “Usufructuaries of earth” focus on Prospections. Throughout the duration of Usufructuaries of earth project and beyond, diverse content—long reads, interviews, conversations, and visual interventions—will incrementally be (re)published into a public research and learning curriculum that studies histories and propositions of usufruct, of renewing shared practices of usership of and with earth.

“We are in the siege of a nature that has been hurt, divided, defiled, poisoned, harmed, and made to bleed,” writes Pelşîn Tolhildan, member of the Kurdish Women’s Movement.

Usufructuaries of earth is the first comprehensive exhibition of Marwa Arsanios’s work in the Netherlands. The exhibition foregrounds the artist’s collaborative approach to bringing together ecological, feminist, and decolonial knowledges and practices that put forward ideologies of usufruct, unhinging property-relations from the idiom of individuated possession and toward forms of common, more-than-human userships. Here is an audio tour of the exhibition given by BAK convenor of research and publications Wietske Maas.