Author(s)

Sven Lütticken

Long weaponized in the service of capital by the agents of neoliberalism, the nation-state is once again upheld as the bulwark of a white ethnos, securing privilege against migrants and immigrants, and against other nation-states in relations of neocolonial dependence.

II. Globalization from Below

III. The Second, Third, and Black Internationals

IV. Non-Alignment Pacts

V. Workingmen and Housework

VI. The Times Are Now

I. Introduction

Long weaponized in the service of capital by the agents of neoliberalism, the nation-state is once again upheld as the bulwark of a white ethnos, securing privilege against migrants and immigrants, and against other nation-states in relations of neocolonial dependence. Meanwhile, contemporary art—the globalist heir to modernist internationalism—has become an investment languishing in freeports or stored in the blockchain, while some try to make up for lockdowns by creating online areas for virtual art “where people from all over the world can meet and network” in a supercharged Second Life aesthetic. 1

Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello have argued that there are two traditions in the critique of capitalism: a social and political critique focusing on inequality and poverty, and an artistic or aesthetic critique targeting alienation and sensuous impoverishment. 2 These two strands, however, have been interlinked practically since the beginning. Much of early socialist thought, as well as Marx’s thinking, can be seen as re-politicizing Friedrich Schiller’s Aesthetic Education, with the end of the division of labor making possible a more sensuously rich and diverse existence. What emerged in the early nineteenth century was a romantic anti-capitalism that lambasted industrialism and alienation while holding up medieval, Christian, feudal society as a positive counter-example. 3 Particularly in Germany, which had no central state, Romantic anti-capitalism fed into the völkische romantic nationalism that became such an important pillar of the nineteenth-century nation-state. As the new capital of the unified Germany during the 1870s–1880s, Berlin was given a pair of monumental buildings inscribed with mirroring dedications: Dem deutschen Volk (to the German People) on the Reichstag and Der deutschen Kunst (to German Art) on the Nationalgalerie. 4

The two mutually imbricated critiques are associated with two strands of avant-garde practice that have a notoriously complicated relationship. In the second half of the nineteenth century, both the leftist political avant-garde and the artistic avant-garde internationalized more fully than they had before, aided by the infrastructures of empire. From steam trains to postal networks and telegraph cables, the communication and transportation infrastructure of imperialism facilitated the emergence of networks of contestation and alterity, and at times, even of forms of transcultural exchange going beyond unilateral appropriation. On the political front, various internationals began to strive for revolution beyond national borders, and while the artistic avant-garde was implicated in colonial ideology (especially when it employed stereotypical and racist imagery of the Other), it nonetheless espoused and lived an internationalism that sets it apart from the dominant ideologies of Nationalkultur of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and its transnational networks have increasingly become the focus of scholarly attention—as have the contacts and overlaps between political and artistic internationalisms. It is thus not only the two critiques of alienation and exploitation that were often intertwined, but also their modes of internationalism, or transnationalism.

If the term “international” evokes, in David Joselit’s words, “a confederation of equal yet distinct traditions” the emergence of globalization since the 1990s suggests “either the erasure of geographic difference (in the so-called McDonaldization of the world) or the emergence of neo-imperial hierarchies that establish boundaries between rich and poor, or between cheap labor and metropolitan finance, that do not conform to the borders of national territories.” In this globalist context, “transnational” has emerged as the adjective of choice to denote exchanges and movements by and between a multitude of (non-state as well as state) actors across national boundaries. 5 If the term itself is frequently used in a neoliberal register where “the mobility of individual agents is [presented as] a dynamic product of freely made economic choices,” my interest here lies with a different set of transnational practices that trouble this utopia: the uneven and unequal global contestation of neoliberal globalization from below. 6

The ideology of personal freedom through economic choices unhindered by state tutelage blossomed in the 1990s, when the rise of the internet was widely heralded as undermining national sovereignty. As John Perry Barlow intoned in his grandiloquent “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace”: “We must declare our virtual selves immune to your sovereignty, even as we continue to consent to your rule over our bodies. We will spread ourselves across the Planet so that no one can arrest our thoughts.” 7 Alongside Stewart Brand and Kevin Kelly, Barlow was the trumpeter of a networked “New Economy” of perpetual growth through innovation—a network economy that would be a de-territorialized “meta-country” of manifold and intimate “hyperconnections” across geographical boundaries, in which “parapolitical organizations” come to take over many of the state’s traditional roles. 8

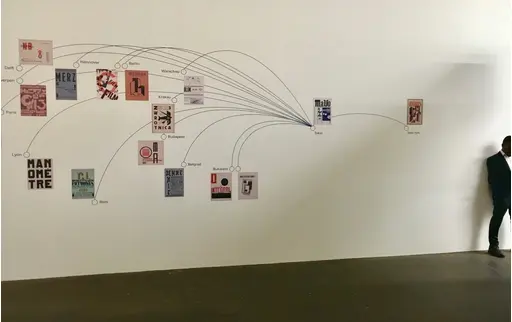

Today, the merchants of neonationalism and neofascism use the platform economy to create discursive and activist networks across the borders they fetishize. An informal international of nationalists has emerged, which Steve Bannon tried to formalize with the Brussels-based organization The Movement (though it does not seem to have taken off). Tracing such far-right networks is now common occupation among political scientists and anti-fascist activists. Likewise reflecting the rise of the network as an “almost contagious concept,” in theory, since the 1990s, if not before, recent scholarship also attempts to reconstruct (in writing and diagrams) the networks of modern artists and revolutionaries. 9 Rather than being placed in linear historical successions, these actors are now seen as operating in dense networks that do, of course, change over time, and can overlap as well as clash. They may be formalized hierarchically, as centralized organizations, such as various political and artistic internationals; they may be more informal and egalitarian networks of friendship and comradeship traversing such hierarchical organizations, or existing in opposition to them. More than ever, formalized internationals need to be seen part of a network of networks that is the always-emerging transnational of planetary entanglement. 10

II. Globalization from Below

In the revolution of 1848, Mikhail Bakunin embraced the idea of the nation-state to defend the national liberation movements of the Poles and Italians: “Salvation for the oppressed Poles, Italians, and all! No more wars of conquest; just one more war should be carried through to its end—a glorious revolutionary struggle with the purpose of eventual liberation for all peoples!” 11 Bakunin demanded an end to “the artificial boundaries which have been forcibly erected by despotic congresses according to so-called historical, geographical, strategic necessities!” and insisted that the only borders should be “those corresponding to nature, to justice, and those drawn in a democratic sense which the sovereign will of the people themselves traces on the basis of their national characteristics!” 12 At this early moment, the arch-anarchist thus was surprisingly state-minded. By contrast, Engels published a resounding rejection of this position in an 1849 newspaper article, on which Rosa Luxemburg built in her 1907 tract on The National Question:

“Nation-states,” even in the form of republics, are not products or expressions of the “will of the people,” as the liberal phraseology goes and the anarchist repeats. “Nation-states” are today the very same tools and forms of class rule of the bourgeoisie as the earlier, non-national states, and like them they are bent on conquest. The nation-states have the same tendencies toward conquest, war, and oppression— in other words, the tendencies to become “not-national.” 13

Founded in 1864, the International Workingmen’s Association—the First International—brought together Marx and Engels with Bakunin’s anarchists to wage asymmetrical warfare against the western nation-states and empires. It proved an unstable mix. In the early 1870s, two twin events would have profound repercussions on subsequent genealogies of inter- and transnationalism: the Paris Commune and its brutal suppression in the spring of 1871, and the Hague Congress of the International Workingmen’s Association in September 1872. One major factor that contributed to the split in the International was, curiously enough, agreement: the universal consensus, from Marx to Bakunin, on the importance of the Paris Commune as a prototype of a society liberated from capitalism, imperialism, and from the state itself.

The anarchist Elisée Reclus later claimed that the overturning of the Vendôme Column by Courbet and other Communards showed that the International’s ideals had become “a living reality,” yet it was precisely this intense focus on the Commune that brought fundamental differences to the fore. 14 For Marx, the Commune was a nucleus of a future communist society, but its suppression had shown the weakness of “prefigurative politics” in the face of the state apparatus—hence, the need to fight for the control over the state, before its later dissolution. Bakunin, on the other hand, regarded the Commune as a concrete model for anarchism in practice. In different ways, both the Marxists and the anarchists grappled with what could be termed the transition problem: with how to effectively move toward the desired future society on which there was, broadly speaking, agreement.

In their preparatory statement for the congress, Fictitious Splits in the International (1872), Marx and Engels asserted that all socialists could subscribe to anarchism as the ultimate goal: “Once the aim of the proletarian movement—i.e., abolition of classes—is attained, the power of the state, which serves to keep the great majority of producers in bondage to a very small exploiter minority, disappears, and the functions of government become simple administrative functions.” By contrast, they continued, Bakunin’s own alliance within the International “proclaims anarchy in proletarian ranks as the most infallible means of breaking the powerful concentration of social and political forces in the hands of the exploiters. Under this pretext, it asks the International, at a time when the Old World is seeking a way of crushing it, to replace its organization with anarchy.” 15 Theoretical differences were compounded by incompatible organizational practices. There is a long history of anarchist Marx-bashing that puts him in the corner of authoritarianism, with Bakunin as his libertarian counterpart. This is a self-serving distortion of the historical record. Bakunin was a grotesque and disastrous throwback to the plotting, scheming, conspiratorial kind of revolutionary, appropriating right-wing conspiracist fantasies both for the purposes of self-aggrandizement (there was always a more secret order or directorate into which Bakunin could initiate you) and discrediting Marx in vituperative antisemitic attacks (alleging that the International had been taken over by a cabal of Jews in thrall to “their dictator-Messiah, Marx”). 16

While Marx failed to reflect on the risk of perpetuating conventional organizational forms, if the revolution was to initiate not just a takeover of the means of production, but a qualitative leap in productive and social relations, Bakunin’s aim “to ensure the Freedom of the sovereign individual Ego” meant that Bakunin’s own ego and power ran unchecked. Whereas Marx, in fact, valued democratic protocol, “Bakuninism in operation meant the imposition of its own authority in autocratic forms: the establishment of a special sort of despotism by a self-appointed elite who refused to call their dictatorship a ‘state.’” 17 Furthermore, as Fictitious Splits in the International rightly noted, Bakunin undermined the project of international solidarity by relapsing into an essentialization of races and the rhetoric of race war. Perversely, he projected his own racism onto Marx, whom Bakunin—the Pan-Slavist—presented as a Jewish Pan-Germanist in league with Bismarck.

Even before The Communist Manifesto (1848), political radicalism was associated in the reactionary imaginary with international organizations, with sinister international conspiracies. The French Revolution and its radicalization, culminating in the execution of Louis XVI in 1793, could not possibly have been the result of a complex and overdetermined chain of events; it had to be the work of devious conspirators. In this context, eighteenth-century conspiracy theories about the Jesuits, and especially about the Freemasons and the Bavarian Illuminati, came in handy. “Revelations” about secret illuminati guidance in the Revolution by the con man Alessandro di Cagliostro; in Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt’s sensational potboiler Le Tombeau de Jacques de Molay (1796), which traced a conspiracy going back to the Knights Templar; and in Augustin de Barruel’s Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire du jacobinisme (1797) created a powerful narrative. 18 Reactionary and usually antisemitic conspiracy theories would accompany later internationals, from the days of Marx to the fascist crusade against both “Judeo-Bolshevism” and “Jewish plutocracy,” echoed in our days by claims that the financier George Soros is behind “Antifa” and Black Lives Matter. 19

The Marx/Bakunin split—which was not quite as “fictitious” as Marx had made out—resulted in diverging genealogies of internationalism. The 1880s and 1890s would in fact be dominated by anarchism: when Marxists founded the Second International at the Paris Congress in 1889—though the organization would not be formalized until 1900—this new international was forced to situate itself against what could be called the decentralized international network of anarchism. In a repressive environment, with various national police forces on guard, there were advantages to decentralization. The anarchist focus on direct action over byzantine theorizations of capitalism appealed to many, from criminals like Ravachol to aesthetes such as Félix Féneon and his painter friends Signac and Pissarro; and, since there was less distrust of such bourgeois artists in anarchist circles than in communist ones, the two avant-gardes could actually come together under the aegis of anarchist spontaneism and terrorist “propaganda by the deed.” Féneon, the dandy art critic, was suspected by the police of having bombed a café. 20 Furthermore, as historian Benedict Anderson notes, “the movement did not disdain peasants and agricultural laborers in an age when serious industrial proletariats were mainly confined to Northern Europe,” which meant that it not only had an advantage in the south of Europe, but also in the Global South—in the colonies. 21

What this amounted to was a “globalization from below,” as Kristin Ross puts it in her account of the Commune refugees’ movements and interactions in Europe during the 1870s and 1880s. 24 Marx himself was active in providing relief to refugees in London, where Communards including the poets Verlaine, Rimbaud and Lafargue had taken refuge—and where Pissarro also lived, though he’d gotten out of France at the onset of the Franco-Prussian War. Ross stresses that the Commune was seen as “an audacious act of internationalism” (as it was called in the Revue Blanche in 1871), turning Paris from the capital of the French state (and empire) into an “autonomous collective in a universal federation of peoples.” 25 As one such commune in a constellation of such collectives across France and beyond, the Commune—had it been allowed to live—would have initiated a form of archipelagic sovereignty. 26 Ross shows that both the communist William Morris and anarchists such as Elisée Reclus and the Russian Peter Kropotkin were aware of the dangers of isolated communes stranded in a capitalist world. However, whereas Morris subscribed to the Marxist point that it is therefore necessary to first abolish capitalism, Reclus and Kropotkin theorized archipelagic forms of cooperation and federation between communities. 27

How can the “second world” be prevented from remaining marginalized? How can globalization from below be turned into an “antisystemic worldmaking project”—to use Adom Getachew’s term for certain forms of postwar decolonization—with repercussions beyond a few pockets here and there? 28 The informal international of networked anarchism and the socialist Second International that was founded in 1889 were the two not-quite-matching halves of such a project.

III. The Second, Third, and Black Internationals

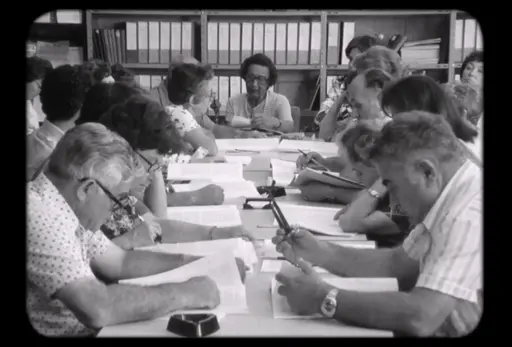

The Second International was not a centralized organization but rather a federation of national socialist parties and unions. While this means that it was clearly based in mass movements and could no longer very well be painted as a backroom conspiracy, the focus on national representative democracy in the end served to undermine it, with Marxist theorist Eduard Bernstein’s reformism marking the inauguration of social democracy as we still (just about) know it. Social democracy regarded the nation state as a “neutral” institutional framework (rather than an instrument of the bourgeoisie) that could be used for progressive purposes. This reorientation notwithstanding, the International maintained a commitment to internationalism, with the Russian and Japanese delegates— Georgi Plekhanov and Sen Katayama, respectively—symbolically shaking hands during the 1904 International Socialist Congress in Amsterdam, while the Russo-Japanese War was in full swing. 29

With its plenary meetings taking place at the swanky Concertgebouw, and others in the Hendrik Petrus Berlage-designed headquarters of the diamond workers’ union, the 1904 conference showed how far the movement had come since the fractious 1872 conference in a cheap dive in The Hague. But the bourgeois trappings could not conceal that this was yet another moment of crisis—and a photo from the police archives identifying key delegates suggests that the authorities may have been jittery. 30 Holland had seen mass strikes in 1903, and unrest was brewing elsewhere: the Russian Revolution would break out in 1905. At this moment, the Dutch party had a strong Marxist revolutionary wing around Anton Pannekoek and the poets Herman Gorter and Henriette Roland Holst. However, the Dutch opposed the French delegate Jaurès’s defense of the general strike as an apocalyptic showdown shutting down every activity, instead substituting a more orderly notion of the mass strike backing specific demands. 31

When the threat of war loomed large in 1912, the internationalist position was reaffirmed—only for the dominant social-democratic elements within the International to cave and rally behind the various war efforts when WWI broke out in 1914. By the following year, the Second International had disintegrated, with both the social democrats and the radicals around Lenin and Luxemburg departing. Lenin’s Third International, or Comintern, would become a dominant force of the 1920s and 1930s, though it was always contested by alternative, non-Bolshevik forms—most importantly anarchist movements, but also the council-communist tendency represented by the likes of Pannekoek and Paul Mattick. Once again, the differences partly revolved around what was a virtually universal agreement on one crucial point: the importance of councils. It was a truth almost universally acknowledged that councils were the nucleus of the coming society, and the early Soviet Union—literally “Council Union”—was marked by the dialectic of dual power between the Soviets and the Party. The Bolsheviks’ suppression of the councils turned the very name of the state into an ideological sham that was relentlessly attacked by anarchists and left-communists alike. 32

C. L. R. James once noted that “each of the three great workers’ internationals [corresponded] in form to a particular stage of capitalism.” 33 Thus, following on the First and Second Internationals, the Leninist Comintern was a quasi-corporate endeavor befitting the age of monopoly capitalism and imperialism. In Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin quotes the economist Hans Gideon Heymann’s analysis of trusts in terms of a “mother company” controlling “daughter companies” and “grandchild companies”: “if holding 50 per cent of the capital is always sufficient to control a company, the head of the concern needs only one million to control eight million in the second subsidiaries.” It is hard not to speculate that Lenin’s Comintern took a leaf out of the book of finance capital as analyzed a few years prior. 34 However, the Comintern’s position as an anti-capitalist counter-multinational was in the end unsustainable if the Soviet Union remained the only socialist country. Trotsky’s permanent revolution sought to foster revolutions in other countries, but Stalin’s doctrine of “socialism in one country” accepted that the Soviet Union was likely to be a singular case for the time being; thus the isolation problem returned on the larger scale of the state itself.

Moscow used the Comintern to support communist movements elsewhere as much as possible, through Moscow-controlled political parties and various front organizations, including many cultural ones. Anti-colonial and Black liberation struggles were likewise turned into branches of this political trust. In this respect, a crucial organization in the Comintern organigram was the ITUCNW (International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers), led by Negro Worker editor George Padmore and later by activist Otto Huiswoud. It has been argued that such (mostly Caribbean and United States American) Black activists sought to create a “Black International” within, or in conjunction with, the Comintern—complemented by a de facto “Black Women’s International” that emerged from the transcontinental activities of activists Hermina Huiswoud, Maude White, Williana Burroughs, and others. 35

Minkah Makalani notes that “Huiswoud and McKay drew on earlier arguments from Asian radicals to stress the international dimensions of race, reframing the Negro problem as a global problem requiring international organization. They joined Roy, Katayama, and others in articulating an intercolonial internationalism through Comintern policy debates.” 39 However, the tendency to reduce racism to an epiphenomenon of class conflict was never fully defeated, nor was the tendency to view the “Negro question” as an American phenomenon, thus undermining any more ambitious transatlantic project. The rise of fascism made the Comintern waver in its support of anti-colonial struggle in favor of alliances and coalitions within democratic capitalist nations in the west. The groundwork for the Popular Front era was laid at the 13th Plenum of the Executive Committee of the Comintern in early 1933, and that same year Padmore severed his ties with the Comintern precisely for what he saw as a betrayal of the anti-colonial cause (the Huiswouds would remain loyal for much longer.) 40

In the context of the Comintern and the affiliated “Black International” of the 1920s and 1930s, the avant-gardes intermingled and frequently all but fused. Anton de Kom’s Wij slaven van Suriname (1934) is a political tract whose forceful prose is of a crisp clarity that turns it into an embodiment of the Nieuwe Zakelijkheid or New Objectivity of the era, and the book came with a modernist cover featuring a photo by the designer Piet Zwart. 41 The art historian Christian Kravagna has called for a “postcolonial art history of contact” that traces people’s movements across networks and their contacts across a world marked by globalization-through-colonization. 42 I would add—though this is clearly implicit in Kravagna’s account—that this needs to be an expanded art history of contact that does not limit itself to a narrow canon of “autonomous” institutional practices. Examples would include the Comintern-backed 1931 La Vérité sur les colonies exhibition, for which the surrealists devised some anti-colonial displays, or the activities of Aimé Césaire (from Paris in the 1930s, to Martinique in the 1940s, and beyond). Of course, such a history is not limited to the Black Atlantic but includes, for instance, India as well as Japan and its colonies.

In recent years, some artistic and curatorial projects have made some of the links and nodes of this network of contacts sensate. It is one thing to see a diagram of Huiswoud’s mid-1930s transatlantic network in a scholarly study, and another to see documents that show the many physical traces of his network in the Black and Revolutionary exhibition at The Black Archives, Amsterdam, in conjunction with works by contemporary artists; or to hear the artist Patricia Kaersenhout read a Langston Hughes poem from a volume dedicated by the poet to Hermina Huiswoud in Wendelien van Oldenborgh’s film Cinema Olanda. 43 Beyond the Comintern context, one can also think of Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa’s archival exhibition on Amy Ashwood Garvey, or Filipa Cesar’s written and filmic work on Amilcar Cabral. Such names represent the rise of Black Nationalism and Pan-Africanism in the wake of the Comintern’s shift to an anti-fascist Popular Front with bourgeois parties, with its decreasing emphasis on anti-capitalism and anti-colonialism.

Here, Michael Denning’s account of a “novelist’s international” is useful: emerging before 1917, this morphing and mutating quasi-movement became allied with Moscow and the Comintern in the Inter-War period (McKay, Hughes, and Richard Wright are part of Denning’s narrative here), and really took off after the 1955 Bandung Conference. Such an account of a multigenerational project allows for an analysis of continuities and transformations in the emancipatory imaginary. 46 Keeping both the potential and the fundamental and structural limitations of modern counter-globalization projects—or anti-systemic worldmaking efforts—in view is essential in light of the current need for coming together differentially under conditions that both necessitate and frustrate such a project. 47

IV. Non-Alignment Pacts

The origins of European integration in the late 1940s and 1950s were marked by a neocolonial project in which the Western-European nation-states, wedged between Washington and Moscow and faced with anti-colonial movements, pledged to join their weakened forces for the collaborative exploitation of Africa (“Eurafrica”). 48 On the other hand, decolonization was marked by nationalism in conjunction with Pan-Africanism and other attempts to build alliances or federations against NATO and the Warsaw Pact. Some, such as Mahmood Mamdani, stress the disastrous afterlife of European colonial ideologies and structures in the newly independent countries, which frequently ended up reproducing the politicization of ethnic boundaries and essentialization of cultural or religious difference. 49

The real decolonization of the political, then, is yet to come—though not without precedent. Getachew acknowledges that compared to Marcus Garvey’s interwar vision of “a deterritorial and transnational mode of belonging that mirrored the imperial geographies of the period,” the postwar project of leaders such as Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah were “increasingly tethered to the territorial form of the nation-state.” 50 Getachew highlights the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester in 1945 and the 1955 Bandung Conference as crucial moments when anti-colonial nationalism asserted the right to self-determination—to a true self-determination going beyond UN-approved forms of neocolonial dependency. In the contemporary imaginary, the Bandung Conference has become a signifier for lost futures. It features, for instance, in The Otolith Group’s essay film The Year of the Quiet Sun (2013), which revolves around Nkrumah’s Ghana—Nkrumah being a participant in the conference—and more generally around African Nationalism and Pan-Africanism.

The film also contains shots of postage stamps from the mid-1960s, and the accompanying installation Statecraft (2014) collects many more. While some of the imagery on the stamps is futuristic and utopian, the postal system itself is an integral part of the infrastructures which European imperialism bequeathed to the Post-War world; The Otolith Group’s works, then, present African decolonization and non-alignment as unfinished business, keeping any definitive historical assessment at bay. 51 In his dialogue with artist Naeem Mohaiemen’s three-channel video installation Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017), Uroš Pajović argues from an ex-Yugoslav perspective that considering the non-aligned movement “lost to history” would be “unnecessarily pessimistic,” and that, beyond “romantic nostalgia and a priori judgment,” it is imperative to “consider these various meetings as a structure of potentialities to revisit, as a set of questions to retrieve and reactivate.” 52 Mohaiemen’s work itself is more elegiac, with sequences on the conflicts that undermined the movement in the 1970s—particularly Bangladesh’s secession from Pakistan. Such secessions spring from the colonial logic of the nation-state, but the existing states could hardly embrace the secessionist dynamic, for fear of their own disintegration. Tito, though, was misguidedly optimistic in 1971, noting that “tribalism” had already been overcome in the Balkans, and would soon fade elsewhere. 53

Being censored did not necessarily endear Maspero to the Situationists, who attacked him for “masperizing” their writings, and who—never to be out-radicalized—rejected the Tricontinental as a proxy for state socialism and assorted variations of Leninism. 56 The Situationist International (SI) can be regarded as yet another postwar “non-aligned” international, pursuing its own form of tricontinentalism separate from the Havana movement. The Situationists sought to resynthesize the artistic and the cultural avant-garde, proclaiming to the fusty International Association of Art Critics (AICA) that “the classless society has found its artists.” 57 In 1963, when Guy Debord noted that the SI could be seen both as “an artistic avant-garde” and as a “contribution to the theoretical and practical development of a new revolutionary contestation,” the group’s emphasis had already shifted to political action and theorizing, with artistic activity being eyed with suspicion of its entanglement in the society of the spectacle. 58. Informed theoretically by Marx, but militantly anti-Leninist and close to Pannekoekian council communism and some forms of anarchism, the Situationists developed a kind of councilist aesthetics that sought to counter alienation through active involvement. In May 1968, the Situationist-dominated Council for Maintaining the Occupations at the Sorbonne sent telegrams extolling “the international power of the workers’ councils” to the despised “communist” party dictatorships in Moscow and Beijng, as well telegrams supporting the anti-Bolshevik Marxist Ivan Sviták in Prague and the radical Japanese Zengakuren student movement.

The disastrous 2018 exhibition on the Situationist International at Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt failed to examine the SI’s councilism and its “tricontinentalism” (just as it failed to examine anything, for that matter). This is in stark contrast to the work of some contemporary artists, particularly Samson Kambalu’s critical dialogue with the Situationist Gianfranco Sanguinetti from a perspective informed by Malawian Nyau culture as a gift economy, and Vincent Meessen’s films and installations connecting the SI to radical struggles in the “Third World”—for instance through its Congolese member, the author Diangani Lungela. 59 The latter co-authored a tract with Debord on Congo, placing the putative Congolese revolution under the aegis of “Lumumba and Liebknecht, Babeuf and Durutti”—and, of course, called for self-management through councils. 60 A more central role in the movement was played by the Algerian Mustapha Khayati—author of Class Struggles in Algeria (1965) and of the tract Setting Straight Some Popular Misconceptions About Revolutions in Underdeveloped Countries (1967). Khayati argues that the seeming triumphs of various anti-colonial and national liberation movements have usually resulted in a rule of bureaucracies claiming to be communist: “the oppressive regimes that have installed themselves wherever national liberation revolutions believed themselves victorious are only one of the guises by which the return of the repressed takes place.” 61

Seeing nothing but dismal version of Bolshevism, “Ben-Bellaism, Nasserism, Titoism and Maoism,” or indeed “Fanonism and Castro-Guevaraism,” Khayati puts a spin on the underdevelopment trope by claiming that “THE ONLY PEOPLE who are really underdeveloped are those who see a positive value in the power of their masters,” and that “The rush to catch up with capitalist reification remains the best road to reinforced underdevelopment,” before intoning (somewhat predictably) that “SO FAR THE REVOLUTIONS in the underdeveloped countries have only tried to imitate Bolshevism in various ways. From now on the point is to go beyond it through the power of the soviets.” 62 A crucial link between the Situationists and the council communist tradition had been the group Socialisme ou Barbarie, with which Debord had been affiliated around 1960. For part of the 1950s, its leading light, philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis, had in turn been close to the Johnson-Forest Tendency—the offshoot of Trotsky’s Fourth International established by C. L. R. James, Grace Lee Boggs and Raya Dunayevskaya.

In 1958 James, Boggs, and Castoriadis co-authored the pamphlet Facing Reality, which argued that the Hungarian uprising was a councilist revolution showing that the working class had no need for “proletarian Jesuits,” i.e., a professional revolutionary vanguard. 63 “In these unprecedented examples of leadership the Workers Councils put an end to the foolish dreams, disasters, and despair which have attended all those who, since 1923, have placed the hope for socialism in the elite party, whether Communist or Social Democrat.” 64 The tract would echo through the 1960s and 1970s—for instance in a 1975 article by then-autonomist (and current hack-in-chief for the right-wing Die Welt newspaper) Thomas Schmid, who analyzed the situation of the post-68 movement under the marvelous Denglish title “Facing Reality: Organisation Kaputt.” 65

For the Situationists, the revolution would have to be a total social and cultural revolution, since even a federation of councils in an otherwise capitalist society would not be able to survive. The specter of isolated islands in the sea of capitalism—too scattered to actually form an archipelago—rears its head again. The problem of prefigurative practice would not go away. Is it possible to create federations, counter-networks of interdependent communist organizations that would be viable under actually existing capitalism? From the 1970s and 1980s onwards, autonomists have continued to create pockets and zones of opacity, pursuing a desertion into such self-governed structures. Such desertions, however, have their necessary counterpoint in activist uses of the infrastructure of the state and of the legal forms that structure relations in the decomposing states of capitalism. Feminists and reproductive rights activists, for instance, were rightly unamused when, in 2016, certain wayward would-be Lenins equivocated between Clinton and Trump, or endorsed the latter with accelerationist “I won’t be hurt by this” bravado.

V. Workingmen and Housework

At the end of the 1970s, drawing on her experiences in both socialist and feminist British organizations in the collective tract Beyond the Fragments (1979), socialist feminist theorist Sheila Rowbotham quoted from Facing Reality to the effect that “the vanguard organisation substituted political theory and an internal political life for the human response and sensitivities of its members to ordinary people.” 66 Rowbotham posits “the growth of new forms of organizing within the feminist movement” as “part of such a larger recovery of a libertarian socialist tradition.” 67 The impact of feminism on the reckoning with the Leninist organizational model, and on “autonomous turn” of the left since the 1970s, can hardly be overstated.

For the longest time, “professional revolutionary” was a male profession. The First International’s full name—International Workingmen’s Association—reflects the gendered nature of labor in industrial capitalism. It comes as no surprise that the activists and theorists who put unwaged domestic or reproductive labor on the agenda in the 1970s—Selma James, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Silvia Federici—created a transnational movement that has been called “the embryo of a Women’s Internationale”:

When it is a question of “network,” it is about the “organizational network” that exists from one country to another, or, if you prefer, the embryo of a Women’s Internationale for wages for housework. In fact, it involves mainly Italian, English, American, and Canadian women. Further, there are “wage groups” that expressly refuse to be part of this network. 68

Once again, then, the International is a fragment, project, and projection, part of a larger constellation that refuses to become a whole. If some expressly refuse to be part of the network, others are connected to the organized network behind Wages for Housework—the International Feminist Collective and its local groups—through a variety of strong and structural, attenuated or incidental links. The real feminist international of the 1970s was a network of networks.

One standard criticism leveled at second-wave feminism concerns its whiteness and refusal to engage with race and racism, with white privilege. Writing about the French Mouvement de libération des femmes (MLF), Françoise Vergès argues that the occlusion of colonialism by French feminists allowed them to position white French women as “the primary victims of oppression,” and that “borrowing the vocabulary of the liberation movements would be a means of reproducing the erasure, forgetting and censorship of the struggles of enslaved and colonized women.” 69 This diagnosis does not apply equally to all nodes and networks. It is significant that James was a veteran of the Johnson-Forest Tendency, and had been profoundly marked by (her husband) C. L. R. James’s analysis of, and participation in, Black radicalism. With Sex, Race and Class (1973) she became a pioneer of intersectionalism, and the Wages for Housework movement at least made efforts to put this into practice.

The informal, confederated feminist international included many artist and media groups, ranging from Women Artists in Revolution to the London Women’s Film Group and L’Insoumuse in Paris. 70 The real ideological turn in relation to media and technology, however, took place in the 1990s, with Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto” (1985), the Australian collective VNS Matrix’s Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century (1991) and Sadie Plant’s writings. These sources were synthesized by the Old Boys Network, a mostly German grouping that organized the First Cyberfeminist International at Documenta X’s Hybrid Workspace in 1997. At that gathering, VNS Matrix (and Old Boys’ Network) member Julianne Pierce noted that their early celebration of the cyberfeminist utopia of the net rang somewhat hollow as the distributed network of the world wide web had given rise to powerful nodes and monopolies: “while we confront our subjectivities, Bill Gates is making $500 a second. Big Daddy is flourishing and the suits control the data stream.” 71 While using somewhat disturbing metaphors (“online frontier woman,” “colonising the amorphous world of cyberspace”), Pierce rightly notes that they’d helped create “a viral meme infecting theory, art and the academy,” which did effectively challenge the male-codedness of computing.

From the 1970s through the 1990s and beyond, feminist organizing—often in the context of or in relation to autonomist self-organization—resulted in the triumph of the other kind of international, whose roots were in anarchism rather than Marxism: not the centralized network, but a decentralized or distributed network of networks. What passes through those networks can be concrete plans for actions, but also theory, galvanizing buzzwords—memes. If 1990s cyberfeminism, culminating in the 1997 Kassel “International,” was “a spam which became hip,” “an impulse which became a commodity,” this has also informed its historical afterlife—generating self-celebratory exhibitions and ever more memeified neo-retro manifestos. As limited as some of these projects are, feminist “memeification,” they can also be regarded as an attempt to reappropriate control over the image of the international.

Historically, the international was a myth or a conspiracy theory before it took on a degree of reality—and while becoming Rorschach blots for fascist fears and fantasies, internationals can try to exploit and mold their image, as one tactic among others. After May 68, the SI found itself turned into “a collective star” by media and hangers-on with a tendency to regard the upheavals as the result of a “worldwide plot by a handful of individuals”; even as the SI as an organization was struggling to continue meaningful work. Always having opted for an exclusive, reductive membership so as to not become a hierarchical mass organization (even though some might argue that on its micro scale it still managed to be plenty hierarchical), the remaining Situationists (Essentially Debord and Sanguinetti) decided to let the myth do the work. The Real Split in the International boasts that “from now on, situationists are everywhere,” and “the more famous our theses become, the more shadowy our own presence will be.” 72 While the SI had clung on to a centralized organizational model for much of its existence—Marx with more than a hint of Babeuf and Bakunin—this statement marks its autonomist sublation.

On the autonomist-feminist front, activist Verónica Gago builds on the International Women’s Strike—an originally Latin American network that has been organizing on International Women’s Day since 2017—to posit a Feminist International. 74 Gago theorizes assemblies and strikes with reference to Rosa Luxemburg and the October Revolution, as well as Selma James and the Combahee River Collective’s pioneering of a socialist identity politics. Although the book explores the notion of the Feminist International less than it does that of the assembly or the strike, it is titled Feminist International; this fits perfectly into the memeification of theory that the publisher, Verso, has been pursuing in recent years, while also suggesting that Gago is not so much concerned with launching an actual organization as with providing a unifying concept for networked activism. Theorizing feminist potencia as a “desiring capacity” that “drives what is perceived as possible, collectively and in each body,” Gago appears to be floating the Feminist International precisely in order to change what is perceived as possible. 75

VI. The Times Are Now

The Non-Aligned Movement’s 1995 conference in Jakarta was accompanied by the Non-Aligned Nations Contemporary Art Exhibition—or the GNB exhibition for short, after the Indonesian name for the movement (Gerakan Non-Blok). Artist and curator Jim Supangkat’s report on the exhibition and its reception suggests a set of complex and often muddled debates taking place after the end of the Cold War, when the Non-Aligned Movement had lost much of its raison d’être—debates about east and west, north and south, and about the possibility of an “international contemporary art” that would no longer be defined in the western centers and subsequently rolled out across “developing” nations. 76 In the 1990s, such debates also fueled, and were fueled by, exhibitions such as the Jakarta Biennale (Supangkat curated the 1993 edition) and the Havana Biennial. From its 1980s editions into the 1990s, when Cuba had to survive without vital Soviet support—the 1989 edition took place at the moment of crisis—the Biennial became a vital form of “soft power” for Castro. 77 In Luis Camnitzer’s words, the Biennial functioned as “an artistic OSPAAAL” that finally became “a provider of the international market.” 78 The real OSPAAAL was closed by the Cuban government in 2019, having outlived its usefulness to the cash-strapped Cuban state, even though in recent years the organization had made strides in monetizing its archive through exhibitions and sales. 79

The 1990s marked the beginning of global contemporary art’s seemingly inexorable triumph. A globalizing, flattening, biennializing sense of contemporaneity seemed the latest form of temporal imperialism; while strides towards provincializing western art and decolonizing institutions were made, contemporary art has nonetheless been part and parcel of globalization from above, with the emergence of new markets and power centers contributing to the emergence of a global elite in a neoliberal world order marked by ever more extreme inequity. Different artists get scooped up by mostly the same galleries updating their profile; updating to remain the same. Some artists operating in this globalized wealth redistribution machine have been invested in revisiting and revising the notion of the international; Tania Bruguera, who realized—or was prevented from realizing—a number of her key projects in the context of the Havana Biennial, created Immigrant Movement International as a project with Creative Time. This was in turn one of the initiatives brought together by artist Jonas Staal, and curators Florian Malzacher and Joanna Warsza in the 2015 event Artist Organisations International at Hebbel am Ufer (HAU) in Berlin. 80

Many of these are “authored organizations” in that they depend on a single artist with a significant amount of capital in the western art world, such as Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International, Renzo Martens’s The Institute for Human Activities (IHA), Ahmet Ögüt’s Silent University, and Milo Rau’s International Institute of Political Murder (IIPM); also represented were different models such as Schoon Genoeg, a cleaners’ trade union campaign with involvement from artists Matthijs de Bruijne, the Laboratory for Insurrectionary Imagination, and groups such as Artists of Rojava, Artist Association of Azawad, and Concerned Artists of the Philippines. The last three have collaborated with Staal’s New World Summit—“an artistic and political organization that develops parliaments with and for stateless states, autonomist groups, and blacklisted political organizations.” Such exercises in organizational aesthetics often entail forms of social montage—people are brought together in constellations and assemblies designed to a greater or lesser extent by the artists—as well as forms of temporal montage.

Western modernity often implies what cultural anthropologist Johannes Fabian has called a “denial of coevalness”: non-western cultures were deemed to live in the past, or some timeless aboriginal state. 81 In contrast to such linear conceptions of modernity, theorists like Peter Osborne have defined contemporaneity as a “coming together of different but equally ‘present’ temporalities or ‘times’, a temporal unity in disjunction, or a disjunctive unity of present times.” 82 This echoes art historian Terry Smith’s insistence that actual “contemporaneity” is the mode of existence attentive to the co-presence of different beings, cultures, temporalities; and that we can speak of truly “contemporary art” only insofar as that art springs from a heightened sense of co-temporality in a fractured yet globalizing world. 83 Building on this, art historian Verónica Tello argues that “projects such as The Silent University, The Immigrant Movement International and The New World Summit reflect and embody the complexities of global contemporaneity—of co-presence, of sharing time—and the uneven social relations (across class, race, gender and other borders) that give it shape.” 84 Such forms of temporal montage and coexistence might perhaps best be characterized as practiced co-temporality, since it may be impossible to redeem the notion of “contemporaneity” in light of the fact that its dominant form is a prolongation and intensification of chrono-imperialism. 85

If Artist Organisations International was essentially one 2015 conference at HAU, Arts Collaboratory has been run for the past decade as “an ecosystem of twenty-five like-minded organizations situated predominantly in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America, all of whom are focused on collective governance.” 89 The project brought together what Marion von Osten has termed “translocal organisations,” which are locally embedded but networked internationally. In her words, these entities defy “the known boundaries between art practices as well as those between art practices and between institutions,” creating “relational work/life models that insist on other ways of doing culture.” 90 Significantly, von Osten’s examples come from regions outside the mainstream of art world capital flows and institutional hypertrophy—and while Arts Collaboratory was established by the Dutch foundations DOEN and Hivos, and was coordinated for years by Casco Art Institute in Utrecht, the network mostly brought together organizations mostly from the Global South, such as Cooperativa Cráter Invertido from Mexico and ruangrupa from Indonesia.

The network of networks is unevenly clustered and interspersed with rifts. Arts Collaboratory was conceived as a corrective mechanism revolving around initiatives from the Global South, though conceptualized in and funded from the Netherlands. The network subsequently attempted to decolonize its structure by giving Casco, DOEN, and Hivos equal status with the other organizations, rather than keeping them in the position of overall directors. At gatherings such as the 2014 Assembly, Indonesia, hosted by ruangrupa and KUNCI Study Forum & Collective, Arts Collaboratory debated and compared forms of practice and organizational structures, as well as funding. 91 If Artists Organizations International focused on para-institutional organizations run by artists intent on using their status in the western art world to realize collaborative yet single-author projects, Arts Collaboratory revolved around what one could call alter-institutional organizations—sometimes artistically and at other times more curatorially driven, though that distinction itself becomes blurry in a practice such as ruangrupa, an artist group curating major exhibitions. For Documenta, ruangrupa uses the Indonesian notion of lumbung (a collective pot or storage) to emphasize “collectivity, resource building, and equal sharing,” working with an “international network of local, community-based organizations from the art and other cultural contexts,” mostly in the Global South—including the Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt in Cuba, founded by Bruguera.[92]

Clearly, a cutting of links between different networks of emancipatory practice will only weaken the left. In the network of networks that is the always-emerging Transnational, or Terrestrial, it makes sense for the different (sub-)networks with their strong links to maintain at least a number of weak ties that enable quick information exchange, coordination, and collaboration.[95] Instead of an all too principled rejection of anything touched by Bernie Sanders, a dual-power approach within the networked left would have to entail a pragmatic division of labor between self-organized autonomists and those seeking to use existing structures for always partial and inadequate—yet for many people non-negligible—gains. Similarly, the networked counter-globalization of ruangupa and its affiliated partners, which uses art infrastructures for its worldmaking project, needs to be seen as the dialectical counterpart of Art of Internationalism’s perhaps more classical rallying behind a political movement—without, however, those artists and organizations being guided by any particular diktats.

If branding and mythmaking have always been always part and parcel of internationals, right up to the “Feminist International” and PI, it is important to conceive of such current entities as part of an evolving constellation, or archipelago. The Transnational or Terrestrial needs to be organized as a network of networks. It needs no secretariat, but requires constant coordination by a multitude of actors. It will never be fully actualized, and may be rumor more than reality—a series of weak links, passages, contacts and conspiracies, or occlusions and manifestations.

Thanks to Nick Aikens, Jonas Staal, and Vivian Ziherl for input and feedback.

[1] See, for example A virtual Utopia. The Area comes alive, Ars Electronica, 2020,areaforvirtual.art

[2] Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Gregory Elliott (London: Verso, 2005), pp. 38–39, 345–472.

[3] The term “Romantic anti-capitalism” was first used in the 1930s by Georg Lukács.

[4] Of course, Bismarck’s new German Reich did not in fact contain the entire Volk; for starters, there was another German-dominated Empire, Austro-Hungary. From the perspective of German nationalism, both Reichststag and Nationalgalerie were thus reminders of a blocked großdeutsche Lösung (Great German Solution).

[5] David Joselit, “‘International Pop’ and ‘The World Goes Pop’,” Artforum 54, no. 5 (January 2016),www.artforum.com

[6] Constance DeVereaux and Martin Griffin, “International, Global, Transnational: Just a Matter of Words?,” Eurozine 11, October 2006,www.eurozine.com

[7] John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” (1996),www.eff.orgBarlow’s Electronic Frontier Foundation, on whose site his writings are archived, applied the settler-colonial spatial concept of the frontier to cyberspace.

[8] Kevin Kelly, New Rules for the New Economy: 10 Radical Strategies for a Connected World (New York: Viking Penguin, 1998), p. 72.

[9] Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), p. 25.

[10] The notion of “planetary entanglement” features in Achille Mbembe’s work, see Necropolitics, trans. Steven Corcoran (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), pp. 93–97.

[11] Mikhail Bakunin, “Aufruf an die Slawen” (1848), quoted in Rosa Luxemburg, The National Question (1907), Chapter 2, www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1909/national-question/ch02.htm#body-10.

[12] Bakunin, “Aufruf an die Slawen,” quoted in Luxemburg, The National Question.

[13] Luxemburg, The National Question. Just before thus passage, Luxemburg quotes from Engels’s article in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, 15 February1849, the authorship of which she mistakenly attributes to Marx.

[14] Elisée Reclus, “Evolution, Revolution, and the Anarchist Ideal,” in Anarchy, Geography, Modernity: Selected Writings of Elisée Reclus, eds. and trans. John Clark and Camille Martin (Oakland: PM Press, 2013), p. 150.

[15] The International Workingmen’s Association [Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels], Fictitious Splits in the International (1872), www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1872/03/fictitious-splits.htm, quoted in Hal Draper, Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution. Vol. 4: Critique of Other Socialisms (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1990), p. 150.

[16] Mikhail Bakunin, “Open letter to the Bologna section of the International” (1871), Michail Aleksandrovič Bakunin Papers, no. 50, search.iisg.amsterdam/Record/ARCH00018/ArchiveContentList, quoted in Draper, Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution. Vol. 4, p. 299.

[17] Draper, Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution. Vol. 4, p. 144.

[18] See J. M. Roberts, The Mythology of the Secret Societies (1972, repr., London: Watkins, 2008), pp. 160–223.

[19] This generates fact-checking pieces with mind-boggling titles such as “No, George Soros is not a Nazi who funds Antifa,” seewww.politifact.com

[20] Joan Ungersma Halperin, Félix Fénéon: Aesthete and Anarchist in Fin-de-Siècle Paris (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), pp. 267–295. If Ungersma Halperin makes a fairly convincing case for Fénéon’s “authorship” on the basis of circumstantial evidence and, at times, of hearsay, a recent Parisian exhibition and catalogue—Félix Fénéon: Anarchiste, critique d’art, éditeur, collectionneur (Paris: Musée d’Orsay et de l’orangerie/Musée du quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, 2019)—sidestepped the question by focusing on Fénéon’s virtuoso performance in court and subsequent acquittal.

[21] Benedict Anderson, Under Three Flags: Anarchist and the Anti-Colonial Imagination (London: Verso, 2005), p. 2.

[22] In the mid-1990s, Andreas Siekmann’s project Wir fahren für Bakunin proposed subverting the infrastructure of neoliberal globalization for an activist-artistic tour through the almost 260 cities where Bakunin hung his hat at some point.

[23] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848), www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch01.htm#007;

Anderson, Under Three Flags, p. 54.

[24] Kristin Ross, Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune (London: Verso, 2015), p. 93.

[25] Ross, Communal Luxury, pp. 11–12.

[26] This Glissantian turn of phrase is used by Léopold Lambert in “The Paris Commune and the World: Introduction,” The Funambulist 34 (March/April 2021), p. 13.

[27] Ross, Communal Luxury, pp. 104–142.

[28] See Adom Getachew, Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), p. 3. Getachew characterizes the International Workingmen’s Association as having constituted the first such project.

[29] “Plechanow und Sen Katayama erheben sich und reichen sic ham Bureau die Hände. Der Kongreß bricht in minutenlangen brausenden Beifall aus.” Brochure Internationaler Sozialisten-Kongreß zu Amsterdam, 14. bis 20. August 1904 (Berlin: Vorwärts, 1904), p. 8,archive.org

[30] Members of the International Socialist Bureau, present at the Congress, held from 14–20 August 1904 in the Concertgebouw, from the Police Archives, Stadsarchief Amsterdam Archief van de Politie, HDAB00001000016_001,archief.amsterdam

[31] See Internationaler Sozialisten-Kongreß zu Amsterdam for the Dutch resolution on the general strike and the report by committee member Henriette Roland Holst (pp. 24–26), as well as the ensuing debate (pp. 26–30), including an interjection by a certain “Pfannkuch,” who must surely be Anton Pannekoek. See also Henriette Roland Holst’s retrospective account in Kapitaal en arbeid in Nederland, part 2 (1932, repr., Nijmegen: Sun, 1973), pp. 82–83, which glosses over the fundamental antinomies that beset the debate at the time.

[32] Invoking “Kronstadt”—Trotsky’s crushing of the Kronstadt soldiers’ council—is a cherished ritual in anarchist and councilist circles.

[33] C. L. R. James (“Johnson”), et al., “Preface (From Second Edition),” in State Capitalism and World Revolution (Detroit: Facing Reality Publishing Committee, 1969), p. 10. Cosigned by “Chaulieu” (Castoridis), this 1956 preface to State Capitalism and World Revolution can be seen as announcing Facing Reality.

[34] Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917), Chapter 3,www.marxists.org

[35] Brent Hayes Edwards, The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), pp. 241–305; Holger Weiss, Framing a Radical African Atlantic: African American Agency, West African Intellectuals and the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 6–7, 292–294, 298; Erik S. McDuffie, Sojourning For Freedom: Black Women, American Communism, and the Making of Black Feminism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), pp. 17–18.

[36] Sen Katayama, “Negro Race as a Factor in the Coming World Social Revolution,” 14 July 1923 (Comintern archives, 495:155:17), quoted in Jacob A. Zumoff, The Communist International and US Communism, 1919–1929 (Leiden: Brill, 2014), p. 313.

[37] Otto Huiswoud (Billings), “The Negro Question at the 4th World Conference,” Comintern Archive at the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History, RGASPI 515/1/93/81—82, 495/155/17/9; quoted in Minkah Makalani, “Internationalizing the Third International: The African Blood Brotherhood, Asian Radicals, and Race, 1919–1922,” The Journal of African American History 96, No. 2 (Spring 2011), p. 172.

[38] Huiswoud, quoted in Makalani, “Internationalizing the Third International,” p. 172.

[39] Makalani, “Internationalizing the Third International,” p. 172.

[40] See Joyce Moore Turner, Caribbean Crusaders and the Harlem Renaissance (Urbana: University of Chicago Press, 2005), pp. 102–104, 155–163.

[41] Anton de Kom, Wij slaven van Suriname (Amsterdam: Contact, 1934). Unfortunately, Zwart’s far more ambitious photomontage of De Kom’s head emerging from a crowd of Surinamese people went unused.

[42] Christian Kravagna, “Toward a Postcolonial Art History of Contact,” Texte zur Kunst 91 (September 2013), pp. 110–131.

[43] On this project, see also Cinema Olanda: Wendelien van Oldenborgh, ed. Lucy Cotter (Berlin: Hatje Cantz/Mondriaan Fund, 2017).

[44] Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (London: Zed Books, 1983).

[45] Mbembe, Necropolitics, p. 74.

[46] Michael Denning, Culture in the Age of Three Worlds (London: Verso, 2004).

[47] The phrase in italics was used by Elizabeth A. Povinelli during her Gerbrands Lecture, 4 March 2021. Seewww.materialculture.nl

[48] Peo Hansen and Stefan Jonsson, Eurafrica: The Untold Story of European Integration and Colonialism (London: Bloomsbury, 2014).

[49] See Mahmood Mamdani, Neither Settler nor Native (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020).

[50] Getachew, Worldmaking after Empire, p. 25. However, Getachew argues that while decolonization appeared to represent the triumph of the Westphalian model, the process challenged international hierarchies and forms of dependence so as to advocate and bring about forms of self-government beyond and against the “Westphalian” international order, see pp. 30–36.

[51] See also The Otolith Group’s related publication World 3 (Bergen: Bergen Kunsthall/Casco, 2015).

[52] Uroš Pajović and Naeem Mohaiemen, “Southward and Otherwise,” ARTMargins 8, no. 2 (2019), p. 89.

[53] Introduction to Pajović and Mohaiemen, “Southward and Otherwise,” pp. 79–80.

[54] Christoph Kalter, The Discovery of the Third World: Decolonization and the Rise of the New Left in France, c. 1950–1976, trans. Thomas Dunlap (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 270.

[55] Kalter, The Discovery of the Third World, p. 269.

[56] See the reference to the Tricontinental in Raoul Vaneigem, “As au civilisés relativement à l’autogestion générlisée,” trans. Ken Knabb, Internationale Situationniste 12 (September 1969), pp. 75–76, www.bopsecrets.org

[57] Seesituationnisteblog.com

[58] Guy Debord, “The Situationists and the New Forms of Action in Politics and Art” (1963), trans. Ken Knabb,www.bopsecrets.org

[59] In 2020, Kambalu and Meessen had a joint exhibition, History Without a Past, at Mu.ZEE, Ostend.

For Meessen, see the other country/l’autre pays (Brussels: Wiels/Sternberg Press, 2018).

[60] Guy Debord, “Conditions of the Congolese Revolutionary Movement,” trans. Not Bored!, www.notbored.org/congo.html, reproduced in Meessen, the other country/l’autre pays, p. 51.

[61] Mustapha Khayati, “Contributions servant à rectifier l’opinion du public sur la révolution dans les pays sous-développés,” Internationale Situationniste 11 (October 1967), p. 41. English translation by Ken Knabb available on Bureau of Public Secrets,www.bopsecrets.org

[62] Khayati, “Contributions servant à rectifier l’opinion du public sur la révolution dans les pays sous-développés,” p. 42. English translation by Ken Knabb.

[63] C. L. R. James, Grace Lee Boggs, and Pierre Chaulieu [Cornelius Castoriadis], Facing Reality (1958, repr., Detroit: Bewick, 1974), p. 89.

[64] James, Boggs, Castoriadis, Facing Reality, p. 10.

[65] Thomas Schmid, “Facing Reality: Organisation kaput,” Autonomie 1 (October 1975), pp. 16–35.

[66] James, Boggs, Castoriadis, Facing Reality, p. 131, quoted in Sheila Rowbotham, “The Women’s Movement and Organizing for Socialism,” in Sheila Rowbotham, Lynne Segal, and Hilary Wainwright, Beyond the Fragments: Feminism and the Making of Socialism (Pontypool: Merlin Press, 2013), p. 132.

[67] Rowbotham, “The Women’s Movement and Organizing for Socialism,” p. 147.

[68] Collectif L’Insoumise quoted in Louise Toupin, Wages for Housework: A History of an International Feminist Movement, 1972–1977, trans. Käthe Roth (London/Vancouver: Pluto Press/UBC Press, 2018), p. 83.

[69] Françoise Vergès, “To Be a Woman, Not a Vision: Delphine Seyrig’s Feminist Quest,” in Defiant Muses: Dephine Seyrig and the Feminist Video Collectives in France in the 1970s and 1980s (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2019), pp. 150–151.

[70] See the introduction by Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez and Giovanna Zapperi in Defiant Muses, pp. 12–74.

[71] Julianne Pierce, “Info Heavy Cyber Babe,” in First Cyberfeminist International, Cornelia Sollfrank and Old Boys’ Network, eds. (Hamburg: obn, 1998), p. 10, monoskop.org/images/7/77/First_Cyberfeminist_International_1998.pdf.

[72] Guy Debord and Gianfranco Sanguinetti, “Theses on the Situationist International and its Time,” in Situationist International, The Real Split in the International: Theses on the Situationist International and Its Time, trans. John McHale (London: Pluto Press, 2003), pp. 53, 71.

[73] See Deserting from the Culture Wars, Maria Hlavajova and Sven Lütticken, eds. (Utrecht/Cambridge, MA: BAK/MIT Press, 2020).

[74] Verónica Gago, Feminist International: How to Change Everything (London: Verso, 2020), pp. 181–210.

[75] Gago, Feminist International, p. 3.

[76] Jim Supangkat, “‘White Paper’ on the Non-Aligned Movement Exhibition,” archive.ivaa-online.org/files/uploads/texts/[English]%201995_GNB_05-16.pdf.

[77] Rachel Weiss, “A Certain Place and a Certain Time: The Third Bienal de La Habana and the Origins of the Global Exhibition,” in Making Art Global (Part 1): The Third Havana Biennial 1989, ed. Rachel Weiss (London: Afterall, 2011), p, 23.

[78] Luis Camnitzer quoted in Gerardo Mosquera, “The Third Bienal de La Habana in Its Global and Local Contexts,” On Curating 46 (June 2020), p. 124.

[79] See Fernando Camacho Padilla and Eugenia Palieraki, “Hasta Siempre, OSPAAAL!” NACLA Report on the Americas 51, no. 4 (2019), pp. 410–421.

[80] See Artists Organisations International online atwww.artistorganisationsinternational.org

[81] Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983).

[82] Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (London: Verso,

2013), p. 17.

[83] Terry Smith, What Is Contemporary Art? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

[84] Verónica Tello, “What is Contemporary about Institutional Critique? Or, Instituting the Contemporary: A Study of The Silent University,” in Third Text 34, no. 6 (2020), p. 638.

[85] Hence a decolonial author such as Rolando Vázquez (in Vistas of Modernity: Decolonial Aesthesis and the End of the Contemporary [Amsterdam: Mondrian Fund, 2020]), posits the need for an exit from the contemporary.

[86] Mbembe, Necropolitics, p. 97.

[87] Kelly Oliver, Earth and World: Philosophy After the Apollo Missions (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015); Bruno Latour, Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge: Polity, 2017); Déborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Ends of the World, trans. Rodrigo Nunes (Cambridge: Polity, 2017); Bruno Latour, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge: Polity, 2018), p. 75.

In Down to Earth, Latour introduces an “attractor” called the Terrestrial (distinct from three other such attractors: the Local, the Global, and the Out-of-this-World) returns us to the familiar level of Sciences Po theory radicalism. If the Terrestrial is to be a political actor, as Latour argues, it needs to be understood precisely as the new International—as something to be built, as artefact.

[88] “Comrade of Time” is Boris Groys’s alternative translation of the German “Zeitgenosse/zeitgenössisch.” See Boris Groys, “Comrades of Time,” e-flux journal 11 (December 2009),www.e-flux.com

[89] See Arts Collaboratory online atartscollaboratory.org

[90] “Trans-Local, Post-Disciplinary Organizational Practice: A Conversation Between Binna Choi and Marion von Osten,” in Cluster: Dialectionary (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014), pp. 274, 283.

[91] Assembly: Indonesia 2014. Working Document, Binna Choi, Gertrude Flentge, and Jason Waite, eds. (2014).

[92] For Documenta Fifteen and the concept of “lumbung” see: www.documenta.de/en/documenta-fifteen/#2578_lumbung.

[93] See Progressive International,progressive.international

[94] See for instance Yassin al-Haj Saleh, “A Letter to the Progressive International,”www.yassinhs.com

[95] See Mark Granovetter’s work, especially “The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited,” Sociological Theory 1 (1983), pp. 201–233. In certain forms of recent theory, such as the theorization of “organized networks” by Geert Lovink and Ned Rossiter, the need for strong links has been emphasized. This should not, however, be seen as an either/or proposition.

Related

The modern nation-state is supposed to be ethnically and culturally homogenous; after World War II, both Israel’s implementation of Zionism and Arab Nationalism adopted versions of this purism—purging and excluding from the body social what refuses assimilation.

As part of FORMER WEST: Documents, Constellations, Prospects, 18–24 March 2013 at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, art critic, poet, and curator Ranjit Hoskote convened a forum on “Insurgent Cosmpolitanism” with cultural theorists and artists whose work addresses and performs the insurgent cosmopolitan condition.

Mariana Botey’s text The State Is Coagulated Blood and Bones is written as a prologue to Cooperativa Cráter Invertido’s codex-comic Sangre Coagulada y Huesos (Coagulated Blood and Bones, 2021). The two contributions have been conceived in collaboration and are to be read in parallel, allowing for a mutual disruption of discourse and image.

Long weaponized in the service of capital by the agents of neoliberalism, the nation-state is once again upheld as the bulwark of a white ethnos, securing privilege against migrants and immigrants, and against other nation-states in relations of neocolonial dependence.

From: New World Academy Reader #5: Stateless Democracy, Renée In der Maur and Jonas Staal in dialogue with Dilar Dirik, eds. (Utrecht: BAK basis voor actuele kunst, 2015), pp. 27–54

From: Once We Were Artists, Maria Hlavajova and Tom Holert, eds. (Utrecht: BAK, basis voor actuele kunst and Amsterdam: Valiz, 2017), pp. 32–52

In 1970–1971, Guyanese radical historian and anti-colonial activist Walter Rodney gave a series of lectures on the historiography of the Russian Revolution at University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Inspired by C. L. R. James’s historical work on the October Revolution, Rodney set out to reveal the parallels between the problems confronting the postcolonial regimes in Ghana and Tanzania, and those that the Bolsheviks faced in building the Soviet state.

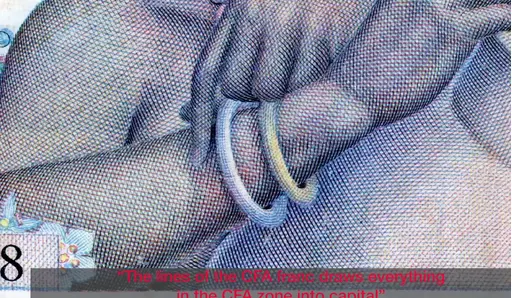

The video The Cut, The Punch, The Press (2021) is assembled from filmed fragments of a collection of 65 banknotes of the CFA franc, circulated between 1945–2021.