Author(s)

Sam Keogh

While walking through the “Nothing To Declare” arrivals gate at London Stansted Airport, Sam Keogh is confronted by three border guards: a pig, a unicorn, and a worried cartoon clock.

Weaving fantasies of abundance and the abolition of work; of feasting and resting; of sabotage, anachronism, and the fucking-up of linear time, Pig Eater is the script to a monologue which was first performed as part of Keogh’s exhibition Sated Soldier, Sated Peasant, Sated Scribe, at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art in London (2021)

The airport was fairly deserted because of Covid, so I was nearly alone. The only other person at the carousel was a guy with a blond mullet in his early twenties, wearing one of those stupid blue Wolfgang Tillmans hoodies with the Frontex flag on the front. Before setting off to find a sausage roll, I went to the bathroom, pausing to take a photo on my phone of a rubbish bin wrapped in a vinyl photo of the Grenadier Guards. I continued, pushing the trolly through the nothing to declare corridor. Because I had nothing to declare . . . but there were three of them . . . all standing proudly in their uniforms, looking at me. To describe this arrangement, from left to right, there was a unicorn, a worried cartoon clock, and a pig. Each one wore a dark navy shirt and tie with epaulets and had Border Force lanyards hanging from their necks. As I said, they were all looking at me, and because I was the only one they were looking at—scrutinizing me for some mistake or clue or transgression—I became guilty, and I averted my gaze in shame.

The unicorn, who seemed a bit younger than the rest, trotted out from the line toward me. I was struck by the glittering perfection of his mane, but contained myself. He whinnied, and said “Please come with me sir,” and ushered me into a side room with metal tables and a large X-ray machine in the middle. He asked me to please put my bag on the conveyor belt so it could be X-rayed; I could only oblige. Then he said, “Do you smoke tobacco or cigarettes sir?”

And I said “Yes occasionally, but only when I drink.”

“Do you have any tobacco on your person today sir?”

I said, “Yes, just about half a pouch of Pueblo, in my carry-on.” He clopped his hoof on the hard lino floor, and asked me to empty my pockets into a small grey tray. I filled it with an iPhone 6 SE; keys; an inhaler; and a lighter with a sloth on it. The tray and the bag rolled through the flaps of the machine’s mouth. We walked around the back of it to meet the bag as it came through the other end.

In that moment, I recalled a short section of Jean Genet’s The Thief’s Journal in which he enigmatically evokes the unicorn tapestries whilst describing the feeling of crossing the border between Czechoslovakia and Poland, at midday, in mid-summer, in a corn field. The air in this scene is a kind of vacuum where the police or the border guards might rush in at any moment to apprehend Genet. He says that this is the most likely place for a unicorn to appear, in broad and frightened daylight, when nothing casts a shadow, at an impossible threshold.

The machine was quite slow to x-ray my bag. The unicorn seemed nervous. Waiting in this silence, and grasping for something to say which wasn’t small talk, he asked me again if I smoked tobacco. I paused a while before answering, confused by the repeated question. Just as I was about to say “Yes” again, his superior trotted over and took the reins. He was the pig. It’s strange to make eye contact with a pig. They have slightly hooded eyes with long blond eyelashes—not unlike mine, but less expressive. The eye itself looks human: its pupil and iris convey a confined intelligence, as if a spell has been cast on a wicked person by a vengeful wizard.

He said “Oink, oink, oink, ‘allo sir, ‘ow are you today? Do you smoke cigarettes or tobacco sir?”

“Yes . . . I”

“Oink, oink, oink, ‘ow much is a pack of cigarettes in Berlin? Oink, oink?” The first question I took to be routine, but the second was more probing. I was trying to make an incision into my previous answer, to test its veracity. There was definitely a wrong answer to this question, which I needed to be careful to avoid . . . but my body betrayed me. It knew this pig was more hostile than the first border guard, and my heart began to race, which made my breathing quicken and my words trip over themselves as they left my mouth.

“I . . . I . . . I . . . don’t smoke straight cigarettes. I smoke rolling tobacco, but only occasionally, when I drink, but I think a pouch of tobacco is about seven euro fifty, I think?” I looked away from his pale eyes. He turned to inspect the bag, and I noticed, on his side, a large incision. A big angular chunk had been carved out of his loin, and beside it, a knife stuck into his skin, waiting for the next slice to be cut. This area didn’t bleed, rather, it steamed. It seemed his whole body was roasted. As soon as I registered this, my mouth began to water. I wanted him now, more than a Greggs.

“Oink, oink, oink, this is a very new bag sir, ‘ow much did it cost?”

I was confused by my body’s contradictory responses to this delicious pig who had the power to indefinitely detain me. “It was 45 euros. I bought it in a Turkish homewares store near Kottbusser Brücke. It was the closest place to my studio where I could buy a suitcase.” I stopped myself there. Why was I volunteering more information than he asked me for? I’m such a fucking lickarse when I’m scared. And why was I scared? I’m a white man, I’ve got a passport, I have a job here, I’m Irish—but that doesn’t mean much anymore.

“Oink, oink, oink, may I open the bag sir? Oink?”

“Yes, of course.” My mind then ran through a Filofax of all possible objects or substances which might have fallen into its folds. I remembered a small baggie of mushroom microdose caps, and I got a flash of panic imagining that I might have left it in there as the pig struggled to open the zip with his stupid little trotter, but I remembered quickly that I left it with my friend Mina, and tried to focus on my breath.

The top of the case popped open with a pressure exerted from the contents squashed inside. It was full to bursting with paper—drawings of flowers, animals, and other objects along with big folded sheets painted red on one side. There was a crumpled Situationist poster; a Sab Cat; and a folded-up life-sized drawing of Ned Ludd holding an alicorn, amongst everything else. And with the opening of the case, something felt as though it had shifted, gravitationally, in the ground of the airport.

One of the flowers fell out and stuck to the pigs greasy crackling belly. A halo of fat bloomed on the paper, and forgetting myself at the sight of the stain, I snatched it off him. He gave a surprised oink. Turning back to the open suitcase he waved his cloven crubeen over the drawings and collages and demanded, “Oink, oink, what’s all this then?” As my appetite began to eclipse my paranoia, I had to fight the urge to bite a chunk out of his cheek. I made my wet mouth move in the shape of an explanation to cover the sounds of my rumbling tum tum.

“They’re a series of collages based on some fifteenth-century Flemish tapestries called The Lady and The Unicorn housed in the Cluny Museum in Paris. Well, not collages, more like proto-collages. They are cartoons, one to one scale drawings which tapestry weavers would use to replicate the designs painted by the artist. What I’m more interested in though is the millefleur motif. It means ‘thousand flowers,’ made up of lots of plants in simultaneous fruit and bloom—a temporally impossible image of abundance. These motifs often have a strangely heterogeneous style, which I believe is because the weavers were free to improvise the flowers. I also like to believe that these flowers were made with a degree of pleasure—that their detailing could slow the work of the weaver to their own pace, using the flowers’ beauty as an alibi for a less strenuous production process, and this might have been a kind of premodern sabotage, siphoning as much time and money and silk out of the aristocrats who commissioned the work in the first place, to make beautiful surfaces of impossible plenty, whose emancipatory message would fly over . . . no . . . under the heads of the rich and powerful and be legible only to the dispossessed of the future.”

The pig looked confused. He didn’t really follow the distinction I was trying to make between tapestries and cartoons, and he said, “Oink, oink, oink, tapestries aren’t made from paper . . . what do you mean tapestries, what tapestries?” By now, my fear of the border guards had completely dissolved, only to be replaced with a more base urge to gorge on roast meat.

But I jumped at the chance to tell the story: “I first saw these tapestries in Paris in 2019, just before everything got worse. My friend and I stumbled upon them in the back of the Cluny Museum. The room which housed them was carpeted and atmospherically controlled. The lights were low and the filtered air smelled of cleaning fluid. People moved slowly, so as to not disturb the insulated stasis. The tapestries glowed with a dim radiance. They were made of silk. Six big red flags scattered with thousands of flowers, animals, birds, and fruits. Each hosting a woman in a dress standing on a floating blue island, and each with a specific object—a mirror, a wreath of flowers, a dainty hand on a horn, etc. There was an elderly man sitting beside me on one of the seating islands. He wore a blue checkered shirt, chinos pulled above his navel, bright white sports socks, and box fresh New Balance trainers. He seemed tall, even while sitting down. He had two walking sticks, which he began to position in front of himself as he tried to stand up. As he lifted himself onto his walking sticks from the seat, he farted very loudly. He didn’t seem to notice or care that it was audible. He had accepted that his body might occasionally need to fart, and so it would fart, and why would we think that funny or objectionable? He was right. And so we weren’t to laugh, and as this enclosed space of reverence filled with the smell of the man’s fart, I looked at my friend Megan. I saw that her mouth was tense with a suppressed smile, and I had to leave the room very quickly for risk of causing a scene.”

The pig seemed to take this story as a license to break wind. It smelled of andouillette, the Lyonnaise pig bowel sausage. I could take it no more. In a fit of ravenous excess, I bit a lump out the pig’s cheek. The unicorn, horrified, lunged at me awkwardly. I instinctively pulled the knife out the side of the swine and lopped off the unicorn’s horn. It hit the floor with a sonorous tinkle and rolled under the X-ray machine. “Now you’re just a sparkly mule, you little bollocks. Go tell the lion prick he’s next.”

He clipped away whinnying with his hooves over his wound. Buoyed up with republican zeal, I continued my explanation to the pig, my mouth full with a large part of his left hind quarter. “Flowers—to return to these flowers, these millefleur—you asked what they were, and now I’m going to tell you. I drew each and every one of them during a Microsoft Teams meeting. It looked like I was taking notes, but I wasn’t. I was drawing pretty flowers on thin layout paper. The drawing of these flowers was narrated by the venal drone of dead-eyed bureaucrats, picking over the corpse of the university. Their beaks clacked with hollow concern for ‘student satisfaction.’”

The unicorn, huddled and bloody in the corner couldn’t get his hooves to work his walkie-talkie. He felt weak from blood loss, but neighed a final desperate plea hoping the cartoon clock would hear. “Heeeeelp!”

The clock burst into the room, somehow not seeing his colleagues’ prone bodies. Instead, his attention was grabbed by another large collage spilling out of the suitcase. It was a big Microsoft Teams calendar, with the days cut out.

“What the fuck is that?”

“It’s a big Microsoft Teams calendar with the days cut out. I was thinking of making it into a kind of trellis for the flowers.”

“What will you do with the days?” gasped the clock.

“I’ll make a kind of shelter from them, and sleep under them when it rains cheese.”

Only then did he see the bodies of the pig and the unicorn on the ground. The unicorn was now dead—his head in a pool of glittering blood which coated a large area of the white lino floor. The pig, a mere husk of bone and gristle, was somehow still conscious. The clock, taking the pig in his arms, demanded an explanation: “What ‘ave you done?!” The ground began to shift again. Gravity tilted toward whoever was looking, and everyone in the airport, including me, fell over. This was somehow a relief. I was glad to be horizontal, because I was so bloated and logy with pork.

Addressing the now-distraught clock, I said: “In 1884, the ball of the Earth was sliced into 24 time zones, all synchronized to the British and their Greenwich Mean Time. 10 years later, a French anarchist, Martial Bourdin, accidentally blew himself up near the Greenwich Observatory. His hand, which held the bomb, was scattered around the park. With his other hand, he held in his guts, which poured out from a massive smoking gash below his navel. Laying on his back in the park, he gazed through the canopy of a plane tree. He was alive and could speak, but revealed nothing of his intentions to police. He was carried to the nearby seamen’s hospital, but died 30 minutes later. It’s my belief that he was trying to destroy time, electing the Greenwich Observatory as its epicenter.”

Confused, and now even more worried, the clock tried in vain to stem the flow of blood from the unicorn’s head wound with paper flowers. There was now no patch of the examination room’s floor that had not turned red from the unicorn’s drained corpse. The clock was silent; he was no longer asking for answers, but he was getting them anyway. I continued, “Some people say that the red flag of socialism originated in Merthyr Tydfil in 1831 when one of the rebels dipped a white banner in pig’s blood. I mean unicorn blood. I mean calf’s blood.”

As the airports gravity intensified, the clock’s hands began to slow. He slurred the phrase “I cannn ffeeelll tthheee grraaavvviiittational ttiiimmmee diiillaaatttiionn.”

I told him this type of gravity was nothing new to me. I was born in it, molded by it. I was good at submitting to it, lying in bed or the bath when I should be up and vertical. I enjoyed feeling its irresistible force crushing other people’s plans for me. I said, luxuriously, “I lay in the bath and I feel time course through my body. The stiller I am, the more I feel it. And I mean that I feel it as an actual sensation. It’s best felt when there are some deadlines on the horizon, especially if those deadlines are close to each other, but far enough away from me that they don’t pose an immediate threat to my languid stillness. I can lay on my back and stare up at this constellation of deadlines and imagine what shapes they might be trying to make: A hammer and sickle, a cornucopia, a dove coot.”

It was then that I noticed the clock’s body was flattening, as well as stopping. The strange gravity falling from the suitcase seemed to be pressing him into his own image. The force was coming from a small painting of a tree, with a circular table of food attached to its trunk. I drew it from an image on my computer of Pieter Bruegel’s Land of Cockaigne which depicted a peasant fantasy land of bloated plenty and no work. Three figures lay at its base, their distended bodies pulled flat to the ground by their own lazy fullness. The unicorn and the pig didn’t escape this gravitational effect either. They too were being pressed into the blood red floor until paper thin, their bodies now surrounded by drawings of flowers, floating to the ground like confetti.

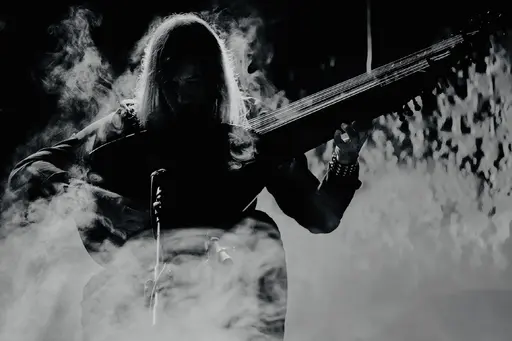

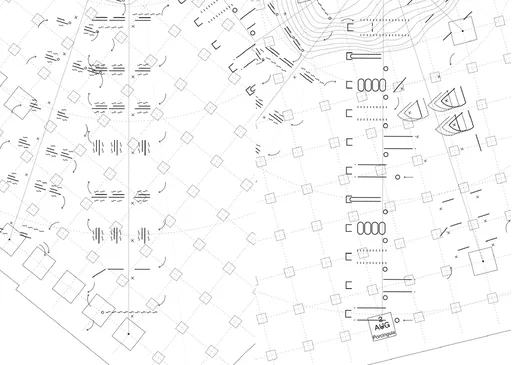

Pig Eater is the script to a monologue which was first performed as part of Sam Keogh’s exhibition Sated Soldier, Sated Peasant, Sated Scribe, at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA), London, in 2021. Images: Sam Keogh, Sated Soldier, Sated Peasant, Sated Scribe, 2021, mixed media installation, courtesy of Sam Keogh, Rob Harris, and Goldsmiths CCA.

Related

“Rhythm Travel” (1995) was published in Amiri Baraka’s short story collection, Tales of the Out & the Gone (Brooklyn: Akashic Books, 2007), republished here with kind permission of Akashic Books.

Temporal drag, erotohistoriography, chronomornativity, horniness under capitalism, rhythm, dancing, and crip time.

Black Quantum Futurism (Camae Ayewa and Rasheedah Phillips) in conversation with Jeanne van Heeswijk and Rachael Rakes.

“The Clearing: Music, Dysfluency, Blackness, and Time” was originally published in Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies, 5, no. 2, 2020, pp. 215–233 and is republished here in revised form with kind permission of the author.

When Indigenous communities are asked to provide proof of their connection to ancestral lands, what Western legal forums accept as documentation does not truly represent or respect tribal culture and traditional formats of knowledge transfer.

How do we reckon with our attachments to place, and their knotted historical relations? A meditation on maritime trade routes, SEA – SHIPPING – SUN (2021), is a short film directed by Tiffany Sia and Yuri Pattison shot over the span of 2 years to render a simulated duration of a day, from The film is set against a soundtrack of shipping forecasts from archival BBC Radio 4 broadcasts. The sun emerges and disappears, again and again.dawn until dusk.

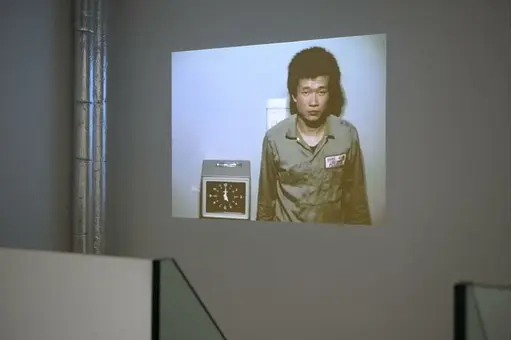

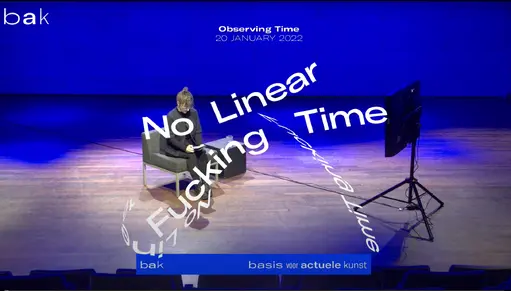

In this essay, Amelia Groom responds to Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980–1981: Time Clock Piece (1980–1981), one of the works on view as part of the No Linear Fucking Time exhibition at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Through a reading of Dolly Parton’s contemporaneous antiwork anthem 9 to 5 (1980), Groom reflects on historical shifts in the ways that workers have been and continue to be exploited through techniques and technologies of time.

Grappling with the imposed linearity of timespace as a fundamental feature of colonial violence, this essay by Promona Sengupta (also known as Captian Pro of the interspecies intergalactic FLINTAQ+ crew of the Spaceship Beben) proposes a mode of time travel that is “untethered from colonial imaginations of the traversability of time and space.”

Weird Times (2021), is a 30-page chapbook by artists Tiffany Sia and Yuri Pattison on time-telling and hegemony. Featuring writing by Sia and images selected by Pattison, it is a brief history of the development of time-keeping technologies. The clock is disassembled as a political tool, a metronome of coercion and an accelerant of war power. Out of these mechanisms, resistant counter-tempos emerge.

An online conversation with performance artist Tehching Hsieh, writer Amelia Groom, and writer and curator Adrian Heathfield, moderated by BAK curator of public practice Rachael Rakes on 20 January 2022. The conversation takes Hsieh’s work as a starting point in addressing performative time, labor time, gaps, and rhythms of endurance, among other things.

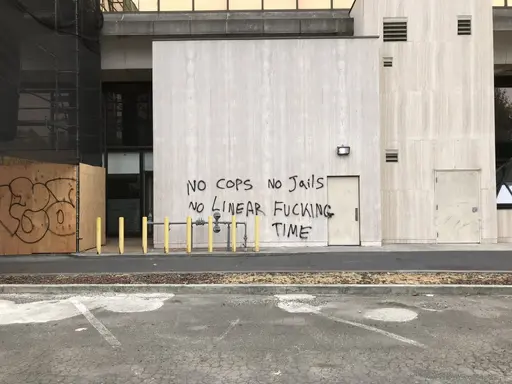

The “No Linear Fucking Time Bibliography” is an evolving resource which compiles selected scholarly and artistic texts relating to the various strands of study involved in this project.

In “Reclaiming Time: On Blackness and Landscape” (first published in PN Review 257 in 2021), poet Jason Allen-Paisant traces the racialized social contexts and modern environmental constructs that “disproportionately rob Black lives of the benefits of time.”

While walking through the “Nothing To Declare” arrivals gate at London Stansted Airport, Sam Keogh is confronted by three border guards: a pig, a unicorn, and a worried cartoon clock.

In this conversation with Walidah Imarisha (first published in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, published by BAK and MIT Press, 2021), the writer and activist outlines her concept of “visionary fiction” as an imaginative practice to emancipate futures from the stronghold of linear time.

Drawing from her work as part of the Karrabing Film Collective, Elizabeth A. Povinelli’s essay “In Some Places the Not-Yet Has Long Been Already” (which first appeared in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, published by BAK and MIT Press, 2021) contrasts the temporal orientation of late settler liberalism—which is troubled by the coming catastrophes of climate collapse—with the ancestral catastrophes of coloniality and enslavement, which are both past and present.

Designed by Rissa Hochberger, with additional design by JJJJJerome Ellis and Kelvin Ellis, the book The Clearing is the eighth title in Wendy’s Subway’s Document Series, an interdisciplinary publishing initiative highlighting the work of time-based artists in printed form.

In her text “Dearest Zen (Letters to Lichen),” artist and scientist Adriana Knouf presents future love letters written to lichens, symbiotic organisms of fungi and algae or cyanobacteria.

In “Immortals: On the Ancient Future Lives of Stone and Plastic,” Marianne Shaneen blends stories, histories, and ontologies of two substances: stone and plastic.

“The Clearing: Melismatic Palimpsest” is a part of musician and writer JJJJJerome Ellis’s multi-faceted project The Clearing (book published by Wendy’s Subway and album of the same name released by NNA Tapes, 2021). Conceiving of the forest and its clearings as “sites of resistant black oralities for centuries,” Ellis explores how stuttering, blackness, and music can figure within practices of refusal against the hegemonic governance of time, speech, and encounter.