Walidah Imarisha in conversation with Jeanne van Heeswijk and Rachael Rakes

Author(s)

Walidah Imarisha, Jeanne van Heeswijk, Rachael Rakes

In this conversation with Walidah Imarisha (first published in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, published by BAK and MIT Press, 2021), the writer and activist outlines her concept of “visionary fiction” as an imaginative practice to emancipate futures from the stronghold of linear time.

Drawing from her work as a prison abolitionist, and speaking specifically to movements and ideas led by Black struggle in the US, Imarisha insists that changing the future will involve being in communion with the past, “specifically in a framework focused on decolonized, non-linear dreams of freedom that are rooted in communities of color’s struggles for autonomy and liberation from colonialism.”

Walidah Imarisha: Visionary fiction is a term—that I started using to talk about imaginative writings and then expanded to art—that can help us understand current power dynamics and support us in imagining ways to build new futures. For me, visionary fiction is intimately and inextricably tied to radical movements for change and to liberation movements. My touchstone for that work was co-editing Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements (2015) with author and activist adrienne maree brown. 1 We were both doing our own work around radical imagination, science fiction, and social change, and came together to create the anthology, the premise of which is that “all organizing is science fiction.”

As folks who have come out of movements for change, we really wanted to support our movements by creating more spaces of imagination, because we are already doing that work—the work of holding the future, every day—anytime we imagine worlds without violence, worlds without prisons, or worlds without borders. Any of these things we’re fighting for, that is science fiction, and that is the work of the future. We want to support our movements by not just saying what we don’t want, but in actively dreaming and then building into existence what we do want. To truly be radical and create the liberated futures that we dream of, we have to go beyond the boundaries of what we are told is acceptable change; we have to go beyond what we are told is possible, because we fundamentally believe that the boundaries of reform are the boundaries of social control. Reform is really the amount of change that existing systems of power will allow to happen. We have to have spaces that allow us to practice imagination, because all of us have been raised in this society where we’re told these systems are immovable. They are almost framed as if they are a force of nature, like gravity: “We must have prison systems,” “We must have borders,” and “We must have capitalism.” As author Ursula K. Le Guin says, “Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.” 2 But first we have to imagine it’s possible. I think there are many different ways to get to that place, and I offer visionary fiction as one of the quantum, countless avenues to get there.

Transformative justice and abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba says, “Hope is a discipline,” and I love that. I envision my approach to my work with the idea that “imagination is a practice.” It’s not a tool, rather, it’s a way of existing, a way of interacting with the world, and a way of constantly creating opportunities to say, “What if?” What if this was more in alignment with my values? What if this included more folks? What if this really breathed the vision of liberation that we have collectively come up with? That is my hope for visionary fiction. It’s important to note that visionary fiction is one of many different ways to get there; adrienne maree brown’s work around emergent strategy is key, because she talks a lot about the need for movements to grow possibilities and entry points. We have to reject “either/or,” because that is a tool of domination—it’s a hierarchy, it’s a dichotomy, and so how do we say instead, as adrienne maree brown always says, “Yes, and . . . .” My understanding is deeply rooted in a study of history and recognizing that we need as many folks doing as many things in a principled way as possible to be successful in dreaming new futures and building them into existence. Every successful movement for change has used a multiplicity of tactics and strategies. Visionary fiction, as a practice, helps us to begin to imagine as many strategies and tactics as possible, but it is not about “This is the one right way,” because I think any time we move in that direction, we’re actually moving away from the futures we want.

JvH: Hearing this, another Le Guin quote is conjured up in my thoughts. In The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) she writes, “To learn which questions are unanswerable, and not to answer them: this skill is most needed in times of stress and darkness.” 3 This speaks to a form of unlearning, of finding other ways to approach questions that one does not know the answer to. Within Philadelphia Assembled (2013–2017), the Futures Atmosphere working group asked questions seeking to reclaim the past and the present in order to decolonize and liberate futures. 4 They built upon your idea that the decolonization of the imagination is the most dangerous and subversive form there is, because it’s where all forms of decolonization are born, because once the imagination is unshackled, liberation will be limitless. You speak about this visionary fiction as a type of fiction, but at the same time it’s a process of decolonization. How would you relate these two processes?

WI: For me, visionary fiction is deeply rooted in my understanding of how we change the future, and it is deeply concerned with that. We cannot change the future without being in conversation and communion with the past, and specifically in a framework focused on decolonized, non-linear dreams of freedom that are rooted in communities of color’s struggles for autonomy and liberation from colonialism. The visions of the future that we’re given in the mainstream are very much an extension of the colonial project.

The idea that the path we’re on is the path that will continue is the same rhetoric that justified colonialism—that we have to continue moving forward and becoming ever better through the lens of white supremacy and western imperialism. It’s important to recognize that true liberation lies in the dreams of freedom, the dreams of community, and the dreams of liberation that our ancestors of color had and held, and continue to have and hold for us. I think it’s crucial to challenge the notion of linear time, which is a method of social control as well. It cuts you off from the past and says that it is lost, it’s unknowable, and it can’t do anything for you, and that the future is similarly also unknowable and unreachable. So all you have is the present, and you just make the best you can in the present and don’t worry about the rest. That is a very capitalist and imperialist notion that is counter to pretty much every culture of color’s notion of time and existence. It’s also the antithesis of our understanding of quantum time and existence as well; we now know that’s actually a fallacy. But Black and Brown folks have known that forever, we didn’t need to wait for quantum physics to tell us that. We live in this sort of decolonized, subversive time travel—that’s how I like to think of it. We know the past is not only available to us, but it’s in communion with us, and the future is actively reaching out for us to help us move forward toward it.

I think the way that the future is framed in our social justice movements and our radical movements is often very uncertain. We don’t hold onto it tightly because we don’t trust that we have the power to make the futures that we want. But we very clearly and strongly hold onto history as a certainty. We say, “This happened on this day.” But when we talk about the future, it’s very tentative: “We hope that this happens,” “Perhaps this is an outcome,” or “Maybe we can do this.” But when we look at history, and specifically the histories of communities of color that imagined liberation that we were told was impossible, we see it’s a historic certainty that oppressed peoples will resist and will win, and we will change the future. We change the entire world to make that possible, time and time again.

So it must therefore be a futuristic certainty that we’ll do the same thing. We need to challenge this notion of linear time, because if we really were in communication and communion with the past, we would recognize that the future is as surely ours as the past is. We really have to root deeply and then spread as far out as the stars to really dream of liberation, because we know from the past we will build a future into existence; it’s incumbent on us to create as much of that future now as we can.

Rachael Rakes: Jeanne, how do you relate what Walidah just said with the idea of training for, or learning for the not-yet?

JvH: When I speak about training for the not-yet, I don’t want to project a future that is linear, or that asks us to create images of what success should look like within the current system—where we have no say about whether that concept of success or progress is one that we would like to embody or to attend to. To me, training for the not-yet means that one actually withholds this projection or linear temporal alignment of futurity, and instead prepares for that which one doesn’t yet know, but hope could arrive. It is a practice in unlearning and committing otherwise to sharing other realities, to other understandings of the past-present or the present-past, and starting to learn from that in order to literally train; not workshopping the not-yet, but actually training to share and commit to other realities in order to build them. For me, this training for the not-yet also asks: What should this learning be built out of? What do we need to learn, and what do we need to unlearn? What do we need to train right now?

WI: I think it’d be interesting to think about the shift from training for the not-yet to living the not-yet. The notion of linear time also embeds within us the notion of fixed geography. Time and space become fixed, as opposed to seeing both time and space as fluid, as quantum, or as existing in multiplicities. So when we frame the futures we want in that way, we recognize there is no destination, right? It’s not-yet! There is no arrival point. Returning to Le Guin, I think the point of her book The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (1974) is the idea that we can make things better, but the minute that we think we have arrived at the destination—or at the time-space intersection of liberation—is the very point that we begin to move away from where we want to be. 5 That it is going to be a continual process, not in a punitive way of “You’ll never get there,” but in an empowered way of “We get to continually reimagine who we are and where we want to be.”

Part of my framing around decolonized subversive time travel is the notion of being able to pull the future into the present. We have the power to do it and we do it all the time. When we create conferences that embody the principles and values that we want to see in all of society, we have pulled the future into the present, although we may only be able to hold onto it temporarily in these moments of meeting or gathering in a certain way. We may only be able to institute it within a certain geographic location—whether it’s at a community organizing space, a workspace, or a cooperative housing space—but we have the possibility of living the futures that we want now, and we do this continually.

The question becomes: How do we continue expanding that out until there is less of a separation between what we want and where we’re at? How do we expand more and more those values, knowing that we’ll never reach the point where the Venn diagram merges and it’s one complete circle?

If that ever did happen it would mean that we’ve stopped dreaming, or we’ve stopped carrying on those liberation dreams of our ancestors by rooting ourselves in a moment, by trapping ourselves under glass like butterflies. But rather, we are in a continuous process of growth, individually and collectively, and so our liberation dreams are in a continuous process of growth, and that is a wondrous thing—it means that there will always be new things that amaze, astound, and surprise us.

JvH: And you describe this as a kind of practice itself, right? It can be a small meeting or a conversation; it can be a different way of doing things that already alludes to where we want to be. By doing that we are practicing it, for example our discussion here now. How do we safeguard motivation so that we can keep practicing it? Because this process is also prevalent with moments of disappointment and doubt.

WI: I think it involves us changing ourselves and changing the ways we engage with one another, to continually allow more opportunities for these moments. I think it’s also about shifting our notion of a “win,” especially in our movements. Oftentimes we’ve allowed the dominant culture to define for us what success looks like, and that definition is something that always leaves us feeling disappointed. So even when we succeed in a certain campaign, we feel defeated. I do a lot of work around abolition, and we stopped one prison from being built, and said, “That’s amazing, but it’s one prison, right? What do we do about all these other prisons?” Rather than saying “No. We won. We won!” There’s always more work to do, so we often add a “but” in there, and I think that comes from society telling us it’s all or nothing, it’s a dichotomy, you win everything or you lose. There’s no middle ground. We should be saying, “We are making wins, we are moving toward these liberated futures. This is incredible, and we’re going to continue doing that.” We all have unlearning to do.

Another reason I look back to history is because it becomes very useful to see moments that, at the time, may have not seemed like full wins, but were incredibly important moments that changed everything that came after them. Thinking about this in relation to prison organizing, I’m reminded about the prison uprising in Attica in 1971 that was in response to the assassination of revolutionary George Jackson, who had been murdered in prison. The Attica organizers issued a list of demands that were visionary then and are still very much relevant today. If we had just fulfilled those freedom dreams of the past, we would be so much further toward the futures we want. But those demands were not met, and were in fact met with brutally horrific state violence. Folks at the time were like, “This is a loss, we did not win,” and yet every movement in prisons that has come since then has referenced the Attica uprising and George Jackson—up to movements that are happening to this day across the US and internationally. The Attica uprising has, for 50 years, inspired countless folks who are incarcerated to not only demand better conditions, but to engage with outside liberation movements. That is an incalculable win. I don’t mean to minimize the horrific loss and the horrific violence and retribution that was exacted upon them by saying that, but looking at history helps us to put our current organizing in perspective. If we are about to imagine something we achieve as a non-win because of what the dominant society tells us, let’s instead imagine how 100 years from now someone might look back at this moment and think, “That was a key moment that helped to change everything. Without it we could not have gotten where we are.”

That is why we need to be able to zoom out and see this immense, pulsating, moving thread of liberation that wraps around itself and curls and flows—that’s when we’re able to really see the importance of what we’re achieving. If we’re able to take that long view, then we trust implicitly—we know implicitly—that even if this amazing thing we’re doing right now ends, we will make so many more opportunities to practice and to be engaged in building the futures we want, while pulling those futures into our existence at the same time.

RR: How might some of the strategies of visionary fiction be applied to activism and organizing? How do we incorporate the different kinds of hope and apprehension from the possibilities of that work into activist work? What are some tactics or exercises for getting activist groups to begin inhabiting or seeing things through these different kinds of temporal understanding?

WI: I’ve developed a number of different workshops, some by myself, and a lot in connection with folks who worked on Octavia’s Brood, especially with organizer and writer Morrigan Phillips, who’s one of our contributors, and adrienne maree brown. I was working on a project about time and the future, and claiming it—that I imagined as a public project—but it turned into a workshop series based on what I call the People’s Encyclopedia of 2070. The concept of the workshop is that we imagine it’s the year 2070, and that we have been winning on issues important to us. I invite people to write entries in the encyclopedia from after these “wins”—entries on moments that helped to change everything. So folks write the futures they want to see as historical fact. So they say, for example, “In the year 2055, the last prison closed in North America,” writing it as if it has already happened. This returns a bit to what I said before about claiming the future with the same certainty we claim the past with, and knowing that we have the right to the future and the right to talk about the future in past tense, because we have the power to make the future whatever we want it to be.

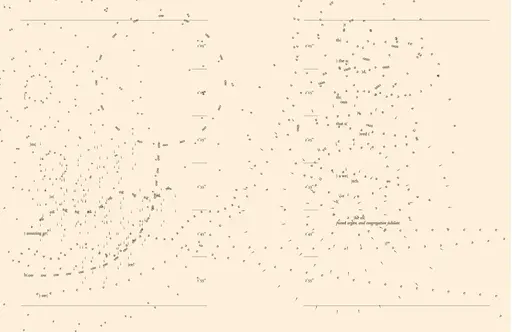

The other piece that has been really helpful is the open format of encyclopedia entries. Folks are free to imagine them in whatever way they want, so some people do drawings and others write creative pieces; there’s space for everything. Because encyclopedia entries usually contextualize the lead up to events, this exercise is useful for allowing folks to break down and visualize timelines. If I want the last prison to close in 2055, then I’m going to need organizing, pressuring for legislative change, combining and connecting social movements internationally, and doing direct action. It allows folks to see the scaffolding necessary to get to these things that we are told are impossible; I hope this process helps ground people in the reality that we are realistically steps away from where we want to be.

The last part of the workshop, after folks write their entries, is to produce a collective zine right there. Everyone walks away with a copy of the zine, so everyone walks away with a tangible thing showing folks’ visions of the future that they collectively imagined. From there, I hope that it becomes something folks can hold onto to remember this moment when we were all together, wrote these futures as fact, and claimed that. That workshop is also useful specifically thinking about strategy and tactics, helping folks to remember that our liberation dreams have to exist beyond two-year grant cycles and five-year strategic plans. We have to be going beyond that to truly build these liberated futures.

JvH: What I find interesting is the way that you describe the encyclopedia entries as a kind of scaffolding that spans history, and that through this scaffolding you actually collapse time. I find it interesting as an oxymoronic metaphor—you build toward a collapse, by moving backward to the present.

WI: I think the goal for me of all of our workshops, and visionary fiction in general, is to create space for folks to be able to dream what they’re being told are impossible dreams, and often that means having to push firmly beyond and disrupt what people consider to be reality, at least in the beginning. You can set a story on a different planet, or very far in the future, so that folks have enough space and they’re not bumping up against the barriers that society has built around what’s possible. But I think the responsibility of the person who is helping to support whatever this dreaming is, in visionary fiction specifically, is to then support the reader or the participant in bringing it back to this time. And that is the aspect that’s incredibly important: that visionary fiction is not utopian or dystopian, because it is firmly rooted in the present whilst still reaching as far as possible into the future. It’s like we’re little stretchy Gumby toys, our legs stay stationary while our bodies stretch as far as possible; it’s not about retreating into a fantasy and staying there. The exercise has to come back to the present to be useful, because the goal of visionary fiction is to change the world in the present and in the future, not to just provide a possibility for folks to engage in intellectual musings. My hope, and I think the hope for most people creating movements, is that the futures we want will come as soon as possible, so the goal is to collapse that timeline, collapse the scaffolding, as much as is healthy and possible.

I also think that this moment that we have been in, in many ways, has shown us that the scaffolding will collapse whether we do it or someone else does. I think that the Covid-19 pandemic has collapsed a lot of the timelines that folks have created, right? That this is where we’ll be, and this is the trajectory of things, and then suddenly everything is heightened, and that future that we thought was 30 years or 50 years in the future, is suddenly much closer. Our movements need to do the same thing, and I think they have been. This iteration of the Black Lives Matter movement, nationally and internationally, has been incredible and incredibly visionary, because embedded in it has been the call to defund or abolish the police. It’s not just calling for accountability from police. It is rejecting the reforms that have been offered for the past 50 or more years and saying, “We have tried all of those things. They do not work. This has to fundamentally change, and we have to imagine beyond what you’re telling us is possible, because we’ve already done everything you’ve told us is possible, and things have not changed on the ground.”

That leap happened very quickly. As someone who’s been an abolitionist for over a decade, that movement from police accountability to defunding and abolishing the police happened in the public conversation very quickly. I believe that is first and foremost because of the courageous on-the-ground organizing, protesting, and mobilizing of especially Black youth who demanded that they be heard, and made it a national and international issue that could not be ignored, by literally putting their bodies on the line in the middle of the pandemic. It is also because of the work of abolitionists who for decades have been holding this space that people have told them was a complete fantasy and unrealistic. Even within radical movements, abolitionists were told, “That’s never going to happen, so why don’t you be more realistic?” It was many women of color, and queer and trans folks of color, folks who should be at the centers of our movements because that’s who said, in a truly liberatory way, “We’re going to dream these impossible dreams and do the work of making them a reality.” When this moment came, it was also because those folks held enough space for this generation to step into that as well. I think that that is part of our work, because if you had asked me a year ago, “When will there be a mainstream conversation where the idea of abolishing the police is debated as a real, legitimate possibility, and when do you think a major city in the US might vote to dismantle their police force?” I would’ve said, “Maybe 2050, maybe? I don’t know, hopefully!”Instead, it was like, “No, it’s in 10 months!”

So if we know that the scaffolding will collapse from outside forces, and that the futures we think are so far away will move closer, the question becomes: how do we do the work so that we are prepared to be ready for that moment? Recognizing that because time is not linear and change does not work in a planned out fashion, we can rest assured that—as the brilliant Black feminist science fiction author and visionary Octavia E. Butler wrote:

The only lasting truth

Is Change. 6

1 Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements, Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown, eds. (Chico: AK Press, 2015).

2 From Ursula K. Le Guin’s acceptance speech at the National Book Awards, 2014, where she was awarded the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

3 Urusula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness (New York: Ace Books, 1969), p. 151.

4 Philadelphia Assembled (2013–2017), initiated by Jeanne van Heeswijk, was an expansive project that told a story of radical community building and active resistance through the personal and collective narratives that make up Philadelphia’s changing urban fabric. These narratives were explored through a collaborative effort between the Philadelphia Museum of Art and a team of individuals, collectives, and organizations as they experimented with multiple methodologies for amplifying and connecting relationships in Philadelphia’s transforming landscape. Philadelphia Assembled asked: how can we collectively shape our futures?

5 Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1974).

6 Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower (1993; repr., London: Headline Publishing Group, 2019), p. 3.

“Living the Not-Yet: Walidah Imarisha in conversation with Jeanne van Heeswijk and Rachael Rakes” appears in Jeanne van Heeswijk, Maria Hlavajova, and Rachael Rakes, eds., Toward the Not-Yet: Art as Public Practice (Utrecht and Cambridge, MA: BAK, basis voor actuele kunst and MIT Press, 2021), republished here with permission of the author. Toward the Not-Yet: Art as Public Practice, is a reader in BAK’s SUPERBASICS series and can be purchased at BAK or via MIT Press.

Related

“Rhythm Travel” (1995) was published in Amiri Baraka’s short story collection, Tales of the Out & the Gone (Brooklyn: Akashic Books, 2007), republished here with kind permission of Akashic Books.

Temporal drag, erotohistoriography, chronomornativity, horniness under capitalism, rhythm, dancing, and crip time.

Black Quantum Futurism (Camae Ayewa and Rasheedah Phillips) in conversation with Jeanne van Heeswijk and Rachael Rakes.

“The Clearing: Music, Dysfluency, Blackness, and Time” was originally published in Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies, 5, no. 2, 2020, pp. 215–233 and is republished here in revised form with kind permission of the author.

When Indigenous communities are asked to provide proof of their connection to ancestral lands, what Western legal forums accept as documentation does not truly represent or respect tribal culture and traditional formats of knowledge transfer.

How do we reckon with our attachments to place, and their knotted historical relations? A meditation on maritime trade routes, SEA – SHIPPING – SUN (2021), is a short film directed by Tiffany Sia and Yuri Pattison shot over the span of 2 years to render a simulated duration of a day, from The film is set against a soundtrack of shipping forecasts from archival BBC Radio 4 broadcasts. The sun emerges and disappears, again and again.dawn until dusk.

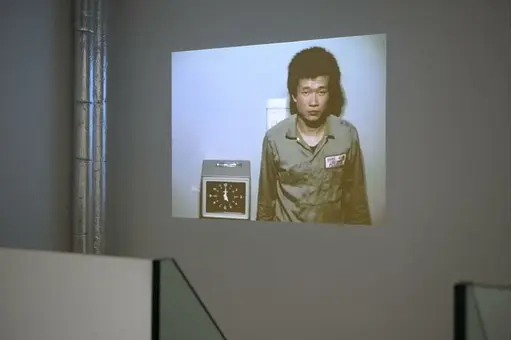

In this essay, Amelia Groom responds to Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980–1981: Time Clock Piece (1980–1981), one of the works on view as part of the No Linear Fucking Time exhibition at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Through a reading of Dolly Parton’s contemporaneous antiwork anthem 9 to 5 (1980), Groom reflects on historical shifts in the ways that workers have been and continue to be exploited through techniques and technologies of time.

Grappling with the imposed linearity of timespace as a fundamental feature of colonial violence, this essay by Promona Sengupta (also known as Captian Pro of the interspecies intergalactic FLINTAQ+ crew of the Spaceship Beben) proposes a mode of time travel that is “untethered from colonial imaginations of the traversability of time and space.”

Weird Times (2021), is a 30-page chapbook by artists Tiffany Sia and Yuri Pattison on time-telling and hegemony. Featuring writing by Sia and images selected by Pattison, it is a brief history of the development of time-keeping technologies. The clock is disassembled as a political tool, a metronome of coercion and an accelerant of war power. Out of these mechanisms, resistant counter-tempos emerge.

An online conversation with performance artist Tehching Hsieh, writer Amelia Groom, and writer and curator Adrian Heathfield, moderated by BAK curator of public practice Rachael Rakes on 20 January 2022. The conversation takes Hsieh’s work as a starting point in addressing performative time, labor time, gaps, and rhythms of endurance, among other things.

The “No Linear Fucking Time Bibliography” is an evolving resource which compiles selected scholarly and artistic texts relating to the various strands of study involved in this project.

In “Reclaiming Time: On Blackness and Landscape” (first published in PN Review 257 in 2021), poet Jason Allen-Paisant traces the racialized social contexts and modern environmental constructs that “disproportionately rob Black lives of the benefits of time.”

While walking through the “Nothing To Declare” arrivals gate at London Stansted Airport, Sam Keogh is confronted by three border guards: a pig, a unicorn, and a worried cartoon clock.

In this conversation with Walidah Imarisha (first published in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, published by BAK and MIT Press, 2021), the writer and activist outlines her concept of “visionary fiction” as an imaginative practice to emancipate futures from the stronghold of linear time.

Drawing from her work as part of the Karrabing Film Collective, Elizabeth A. Povinelli’s essay “In Some Places the Not-Yet Has Long Been Already” (which first appeared in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice, published by BAK and MIT Press, 2021) contrasts the temporal orientation of late settler liberalism—which is troubled by the coming catastrophes of climate collapse—with the ancestral catastrophes of coloniality and enslavement, which are both past and present.

Designed by Rissa Hochberger, with additional design by JJJJJerome Ellis and Kelvin Ellis, the book The Clearing is the eighth title in Wendy’s Subway’s Document Series, an interdisciplinary publishing initiative highlighting the work of time-based artists in printed form.

In her text “Dearest Zen (Letters to Lichen),” artist and scientist Adriana Knouf presents future love letters written to lichens, symbiotic organisms of fungi and algae or cyanobacteria.

In “Immortals: On the Ancient Future Lives of Stone and Plastic,” Marianne Shaneen blends stories, histories, and ontologies of two substances: stone and plastic.

“The Clearing: Melismatic Palimpsest” is a part of musician and writer JJJJJerome Ellis’s multi-faceted project The Clearing (book published by Wendy’s Subway and album of the same name released by NNA Tapes, 2021). Conceiving of the forest and its clearings as “sites of resistant black oralities for centuries,” Ellis explores how stuttering, blackness, and music can figure within practices of refusal against the hegemonic governance of time, speech, and encounter.